Wishful Thinking: 6 'Magic Bullet' Cures That Don't Exist

Magic bullets

Wouldn't it be nice if you could just take a pill and become smarter, stronger and faster? Science has brought us a lot of advances, but here are a few enhancements we've yet to see.

A pill to make you smarter

The fantasy of popping a pill and becoming a modern-day Einstein is dramatized in the 2011 movie "Limitless," in which a man takes a memory-enhancing drug and becomes a genius. Sounds like a great way to save yourself hours of studying, but science just hasn't come up with a way to boost our brainpower like that.

Which is not to say they haven't tried. Memory-enhancing drugs are a major area of research, given the devastating effects of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Scientists are beginning to discover molecules in rodent brains that play a role in enhancing and blocking memories, but how this would work in humans is anyone's guess.

Some college students already use black-market attention deficit disorder drugs such as Ritalin and Adderall to power study cramming sessions, but those drugs have side effects, including heart problems and dependency, and they may not do much to boost brainpower anyway. Besides, the mind is a well-oiled machine, Alcino Silva, a memory researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, told LiveScience in March 2011.

"Our biological systems are the results of finely balanced mechanisms," Silva said. "If you muck with them, it's at your own peril."

Related: Himalayan salt lamps: What are they (and do they really work)?

A pill to make you small

Weight-loss drugs are likely one of the most lucrative nonexistent "magic bullets" out there. According to a 2011 report by Marketdata Enterprises, Inc., the weight-loss industry (which includes meal services, diet pills and plans and some medically supervised programs) was worth $60.9 billion in the U.S. in 2010. Many supposed weight-loss drugs are sold as supplements and aren't FDA-approved, though the agency has warned that some are tainted and potentially toxic.

Another problem with weight-loss supplements? They don't really work in the long run. And many, like a fad that involves eating 500 calories a day and taking injections with a drug made from the urine of pregnant women, can be dangerous.

Even the most effective anti-obesity treatment we have, bariatric surgery, requires major commitment and lifestyle change. So far, there's no effortless, side-effect-free way to shed pounds.

Male "enhancement"

There wouldn't be so much spam about it if men weren't looking for a way to extend what nature gave them. Penis enlargement is a big business, with plenty of hucksters shilling pills supposedly capable of providing more size.

Unfortunately, penis-enlarging pills just don't work. The one method that does show some results, mechanical traction, requires a bit more commitment than downing a tablet. Some studies have shown that penis stretchers, worn six hours a day for four months, can add 0.7 inches (1.8 cm) of length to the sex organ.

Thing is, most men don't need this magic bullet. The vast majority of men seeking information on larger penises aren't in the abnormally small range. More often, they've internalized messages from pornography and media that bigger is better.

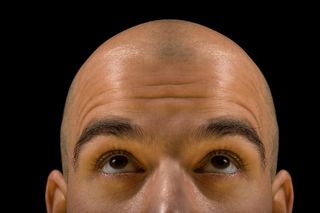

A never-go-bald hair tonic

There's little to be done about a receding hairline, short of a snazzy buzz cut. Minoxidil, the anti-baldness drug best known by the brand name Rogaine, can increase hair growth in young men with balding on the top of the head, but it has no effect on the creep of hair back from the forehead. Likewise, the anti-hair loss drug Propecia (finasteride), hasn't been shown to reduce hair loss around the temples — and it can't help men grow back all of the hair that's already been lost.

The fountain of youth

Would you like to live forever? Immortality may be a little extreme, but many people would jump at the chance to live longer with fewer infirmities. There are good ways to increase the likelihood of a long, healthy life — diet and exercise, anyone? — but scientists have yet to come up with a way of pushing life expectancies over 100.

The most intriguing life-lengthener so far is calorie restriction. Animal studies over the last three decades have found that cutting daily calorie intake significantly increases lifespan. And the older animals seem younger and healthier than their unrestricted counterparts.

Studies in primates are ongoing, so it's not yet known if humans could benefit from restricting calories below the recommended amount. And anyway, a life of hunger hardly counts as a magic bullet. Now, scientists are researching the genetic changes that happen in calorie-restricted animals, looking for a way to mimic those changes in humans with pharmaceuticals.

Love potion

Imagine cutting through the pesky world of wining, dining and actually having to be nice to someone to win his or her heart. Love potions have entered the realm of pseudoscience thanks to the discovery of oxytocin, a hormone important for monogamy and pair-bonding.

Online, retailers sell products like "liquid trust," a spray purported to contain oxytocin that is supposed to make co-workers, family members and potential romantic partners feel warm and fuzzy toward you.

Yeah, right.

While oxytocin is no doubt important in making us feel close to one another, it is not an "indiscriminate love drug," according to University of Amsterdam psychologist Carsten K.W. de Dreu. Research has shown that oxytocin has a dark side: It can make us feel less trusting of people we perceive to be outside of our social sphere, for example. The hormone also does nothing to increase trust in someone you know to be unreliable. In other words, we aren't slaves to our hormones — or to supposed magic potions.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.