Neptune Shines in New Photos Marking First Orbit Since Its Discovery

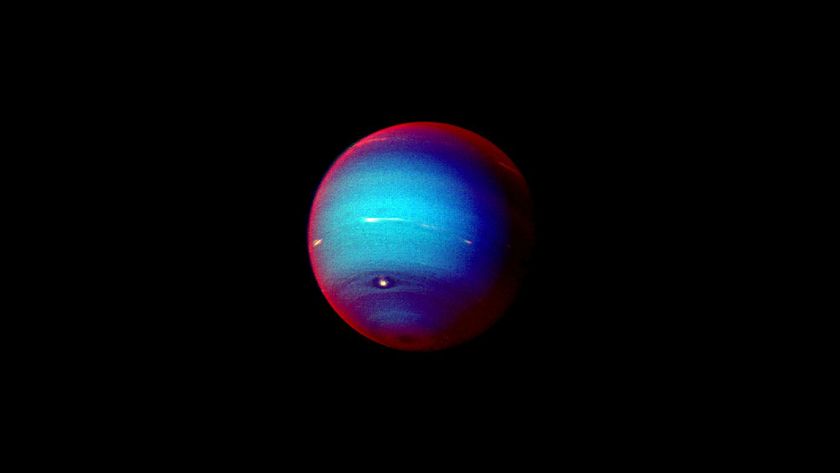

The gas giant planet Neptune takes center stage in a series of sharp new photos snapped by the Hubble Space Telescope in honor of the blue-green world's first Neptunian year around the sun since it was discovered in 1846.

Today (July 12), Neptune completes its first trip around the sun since being discovered nearly 165 Earth years ago — on Sept. 23, 1846, to be exact, by German astronomer Johann Galle.

Neptune takes about 165 years to complete one orbit around the sun. It is about 30 times farther from the sun than Earth and typically orbits at a distance of about 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion kilometers). [Photos of Neptune: Latest Hubble and Voyager Views]

Big, blue Neptune

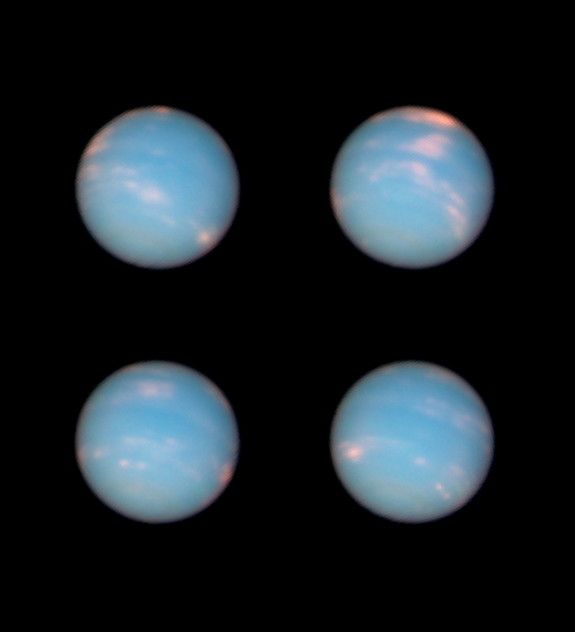

The four new Hubble photos show Neptune in stunning detail.

The images were taken about four hours apart and show the planet as it appeared between June 25 and 26 over the course of a single Neptunian day, which lasts about 16 hours, yielding a complete view of the distant world.

In a photo description, scientists said the new Hubble photos revealed more high-altitude clouds on Neptune than those seen in recent observations within the last few Earth years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The clouds are composed of methane ice crystals and hover over parts of Neptune's northern and southern hemisphere, Hubble scientists said.

Like Earth, Neptune spins on a tilted axis, which gives the planet its own set of seasons. Earth's axis is tilted about 23 degrees, but Neptune has a more pronounced 29-degree tilt.

While Earth's seasons tend to last a few months each, a single season on Neptune runs for about 40 Earth years, scientists explained. Currently it is early summer in Neptune's southern hemisphere and winter in the north, they added.

The large temperature differences between Neptune's warm interior and its super-chilly cloud tops, which can reach minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 162 Celsius), may be responsible for large-scale weather changes, Hubble scientists said.

Discovering the eighth planet

The story of Neptune's discovery in the 19th century is unique among the planets of the solar system. It was the first planet

to be discovered using mathematics, with astronomers predicting Neptune's position after observing that the orbit of Uranus — the seventh planet from the sun — did not exactly match up with Newton's theory of gravity.

According to NASA, it was the French astronomer Alexis Bouvard in 1821 who first speculated that another planet was tugging on Uranus and tweaking its orbit. By 1841, mathematician-astronomers Urbain Le Verrier of France and John Couch Adams of England had each independently predicted the location of this mystery planet.

Le Verrier passed the information on to the man who would actually discover Neptune — German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle of the Berlin Observatory — and Galle spotted the planet less than a degree from its predicted location during a two-night campaign in September 1846.

"The discovery was hailed as a major success for Newton's theory of gravity and the understanding of the universe," Hubble scientists said.

Still, while Galle is credited as Neptune's discoverer, he wasn't the first person to actually see the planet.

In December 1612, the famed astronomer Galileo Galilei recorded an observation of Neptune, which he described as a "star" in his notebook while making observations using a handmade telescope, Hubble officials said. Later, in January 1613, Galileo noticed that the so-called "star" had shifted position in relation to other stars, but he never actually identified the object as a planet or followed up that initial observation.

That leaves the honor of Neptune's discovery securely with Galle.

Neptune is so far away that it cannot be seen with the unaided eye. A small telescope or binoculars can resolve the planet. Currently, Neptune can be found in constellation Aquarius, close to the boundary with Capricorn, Hubble officials said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com Managing Editor Tariq Malik on Twitter @tariqjmalik. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Tariq is the editor-in-chief of Live Science's sister site Space.com. He joined the team in 2001 as a staff writer, and later editor, focusing on human spaceflight, exploration and space science. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times, covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University.