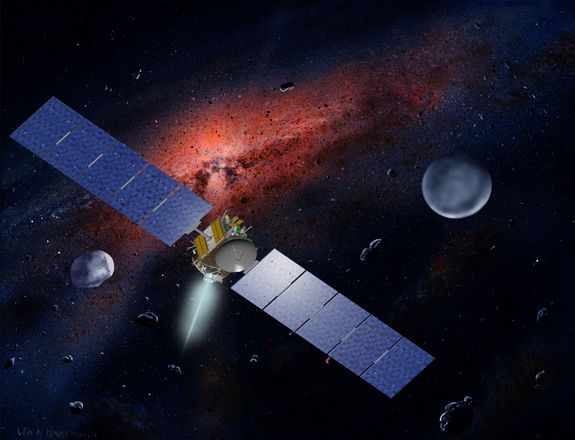

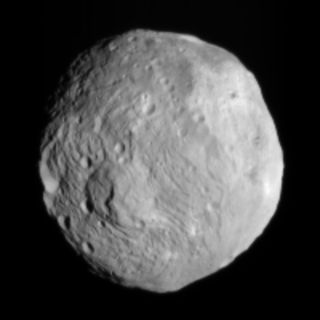

A NASA spacecraft is poised to slide into orbit around the massive asteroid Vesta tonight (July 15), marking the start of the first extended visit by a probe to a large space rock.

After traveling more than 1.7 billion miles (2.7 billion kilometers), NASA's Dawn spacecraft is expected to be captured by Vesta's gravity at about 10 p.m. PDT Friday (1 a.m. EDT Saturday), NASA officials said. Dawn will circle the Arizona-size asteroid for the next year, making observations that could help scientists learn more about the early days of the solar system and the processes that formed and shaped rocky planets like Earth and Mars.

"We've been waiting a long time to get here," said Dawn project manager Robert Mase, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Everybody's really excited as we're starting to inch closer and closer." [Photos: Asteroid Vesta and NASA's Dawn Spacecraft]

A mission that almost didn't happen

Dawn is nearly four years into a journey that almost didn't get off the ground. NASA approved the mission in 2001 but canceled it in March 2006 because of concerns about cost overruns and technical challenges.

The space agency reconsidered just a few weeks later, giving Dawn the go-ahead for a 2007 launch. The $466 million mission blasted off in September of that year, and the spacecraft has been chasing Vesta ever since. And now it has nearly caught its quarry, which at 330 miles (530 km) wide is so big that many astronomers classify it as a protoplanet.

Vesta is the second-largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Scientists believe Vesta was well on its way to becoming a full-fledged rocky planet before Jupiter's gravity stirred up the asteroid belt long ago. The dwarf planet Ceres is the only larger occupant of the belt.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike other types of spacecraft, Dawn won't have to make any dramatic, last-second maneuvers to enter into orbit. The probe has been using its low-thrust ion propulsion system to close the gap on Vesta slowly but surely, and it should simply ease into orbit at about the predicted time.

"We're in an orbit that's very similar to Vesta's now around the sun," Mase told SPACE.com. "We just need to keep thrusting, and then eventually we get to the point where technically we're captured."

Captured by a huge asteroid

The capture should occur when Dawn is approximately 9,900 miles (16,000 km) from Vesta, researchers said. At that point, the spacecraft and asteroid will be about 117 million miles (188 million km) from Earth. [Infographic: How NASA's Dawn Asteroid Mission Works]

It will take a day or so to confirm that Dawn is actually in orbit, Mase added. That's because the spacecraft cannot communicate while it's thrusting and its antenna is pointed away from Earth. Dawn will re-orient itself to touch base with mission controllers at about 11:30 p.m. PDT Saturday (2:30 a.m. EDT Sunday), researchers said.

But if for some reason Vesta does not capture Dawn on schedule, it's probably not a disaster for the mission.

"We do have flexibility and the ability to catch up if we end up falling behind," Mase said. "We're never at a point where we just fly on by and that's it."

First Vesta — then Ceres

Once it arrives, Dawn will initiate a yearlong study of Vesta using three instruments: a camera, a spectrometer, and a gamma ray and neutron detector.

Dawn will map the giant asteroid's surface fully, study Vesta's composition and investigate its geological history. The spacecraft will do this from several different orbits, ranging in altitude from 1,700 miles (2,700 km) to just 120 miles (200 km), researchers said.

When that work is done in July 2012, Dawn will slowly spiral away from Vesta and head off toward the dwarf planet Ceres. Dawn will undertake similar research at Ceres, which is 590 miles (950 km) wide, once it gets there in February 2015. It will become the first spacecraft ever to orbit two different objects in the solar system beyond the Earth and moon.

Though they both reside in the asteroid belt, Vesta and Ceres are very different bodies. Ceres is more primitive and wet, possily harboring water ice, Mase said. Vesta seems to be more evolved, drier and rockier.

A detailed study of these two gigantic asteroids could shed light on how rocky bodies coalesced and evolved in the early days of the solar system, researchers said. This information could bear on how our own planet — and Mars, Mercury and Venus — came to be.

"The mission goals are really to be able to compare and contrast those two bodies to understand how they evolved, what they say about how the other planets in the inner solar system evolved and how they could be in roughly the same place around the sun and yet be such very different bodies," Mase said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.