Mutant Sperm May Explain Mysterious Cases of Male Infertility

Many enigmatic cases of infertility could be explained by a newfound mutation that keeps sperm from reaching eggs, a new study suggests.

These findings could improve screening and treatment of infertile couples, an international team of researchers said.

Infertility affects 10 to 15 percent of the U.S. population, with about half of those cases involving problems with male fertility. One of the mysteries of infertility is that sperm quality and quantity seem to have little to do with whether or not a man is fertile.

"In 70 percent of men, you can't predict their fertility on the basis of sperm count and routine assessment of quality," said researcher Gary Cherr at the University of California at Davis.

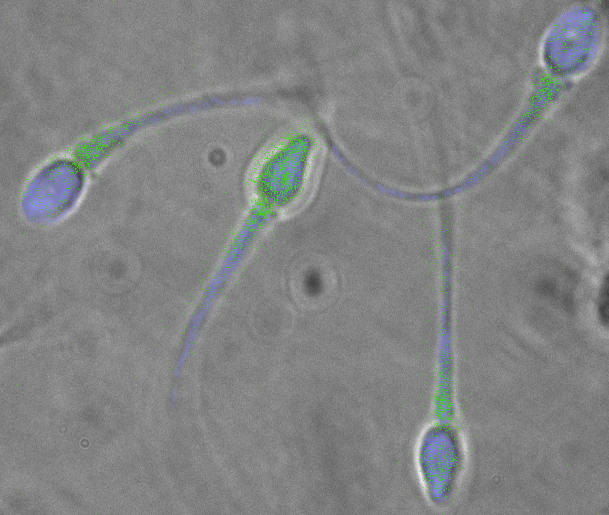

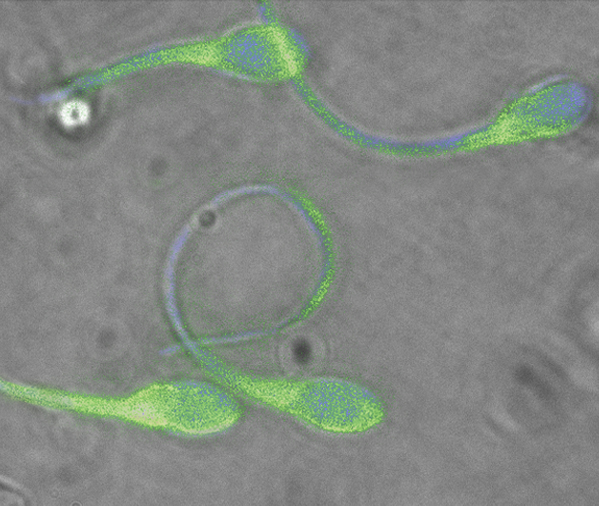

The new clues regarding infertility that Cherr and his colleagues discovered have to do with a gene called DEFB124 that encodes beta-defensin 126, which belongs to a germ-killing class of proteins. A thick coat of this molecule is applied onto sperm in the coils of the epididymis, the structure where sperm are stored after they are generated in the testicles. [5 Myths About the Male Body]

Beta-defensin 126 helps sperm swim through the mucus in the cervix, the neck of the womb. As such, it acts kind of like a "Klingon cloaking device," Cherr said, helping sperm sneak their way to an egg.

Men with two mutant copies of DEFB124 lack beta-defensin 126. Their sperm look and swim normally when seen under a microscope; however, the scientists discovered the little swimmers are about 85 percent less able to make their way through an artificial gel resembling human cervical mucus, revealing how this genetic defect likely accounts for many hitherto unexplained cases of infertility.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In an analysis of more than 500 newly married Chinese couples, the investigators found men who had two mutant copies of the gene had lowered fertility — their wives were 40 percent less likely to become pregnant than other couples. This even proved true of men with the mutation who did not display other problems typically linked with infertility, such as low sperm count and reduced sperm motility.

The mutation is not limited to China. A survey of DNA samples from the United States, United Kingdom, China, Japan and Africa showed that about half of all men carry one defective copy of DEFB126 and about a quarter have two mutant copies.

The upshot

These findings are surprising, as one might expect a mutation that dramatically affects fertility to be much less common, since carriers would have less offspring and thus make up less of the population. It may be that men with one normal and one defective gene but normal fertility are advantaged in some way, speculated researcher Ted Tollner at the University of California at Davis.

Another possibility is that because humans breed in long-term monogamous relationships, unlike most mammals, sperm quality does not matter as much, Cherr suggested. Tollner noted that human sperm are typically slow swimmers with a high rate of defects when compared with that from monkeys and other mammals.

However, some researchers do think that human fertility has been falling worldwide in recent decades. That problem could be linked with the commonality of defects in this gene. Cherr said the researchers next hope to work with a major U.S. infertility program to explore the role of the mutation. [5 Myths of Fertility Treatments]

Future research could lead to bothclinical and home infertility tests looking for this mutation. Couples then could be treated with a procedure known as intracytoplasmic sperm injection or ICSI, in which eggs are removed from a woman and injected directly with sperm, avoiding an expensive workup to exclude other causes, said male infertility specialist John Gould at the University of California at Davis.

Another possible intervention for such couples might ultimately be synthetic forms of beta defensin 126 that can be added to sperm. "You can concentrate it in a vaginally applied cream or gel, and sperm would pick up this defensin coat as they advanced into the cervix," Cherr said.

Ironically, although these findings hold the promise of fertility, they owe their origins to research into a novel type of contraceptive. The scientists were investigating proteins coating sperm for potential targets of a vaccine — the immune systems of recipients of such a treatment would then go on to recognize and destroy sperm, Tollner told LiveScience.

"We didn't investigate this for purposes in humans, but for purposes in canines — to help manage dog and cat populations," Tollner explained. There is research into such immunocontraceptive vaccines for humans, but he noted the resulting contraceptive effect appears only temporary.

The scientists detailed their findings online July 20 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Is getting an IUD painful?

'Useless' female organ discovered over a century ago may actually support ovaries, study finds