Ancient Dino-Eating Croc Had Huge Teeth, Dog Face

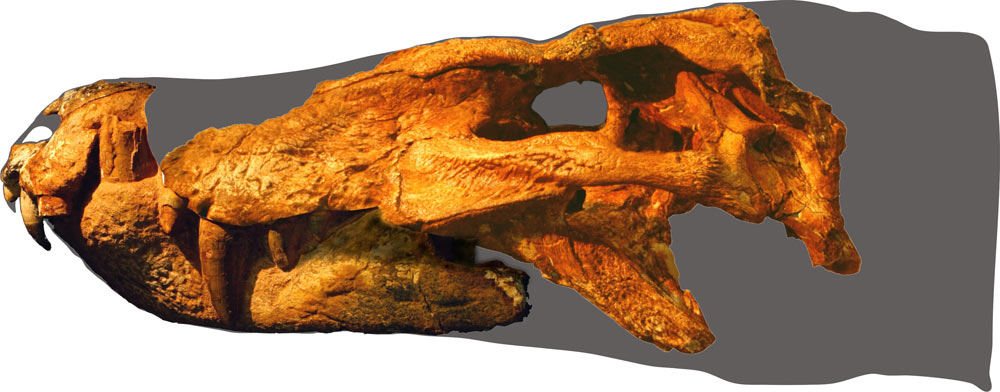

A crocodilian fossil with big teeth and a doglike skull is now shedding light on the anatomy of a strange group of predators, scientists have revealed.

The fossil was unearthed by a municipal worker in a small town in Minas Gerais, Brazil. It dates back 70 million years, near the end of the Age of Dinosaurs.

"Whereas modern-day amphibious crocodiles have low and flat heads, this new find gives us one of the first detailed insights into the head anatomy of this weird group of extinct crocs called Baurusuchia that feature tall, doglike skulls with enlarged canines, and long-limbed body proportions," said researcher Hans Larsson at McGill University in Canada. [Pictures of Monster Reptiles]

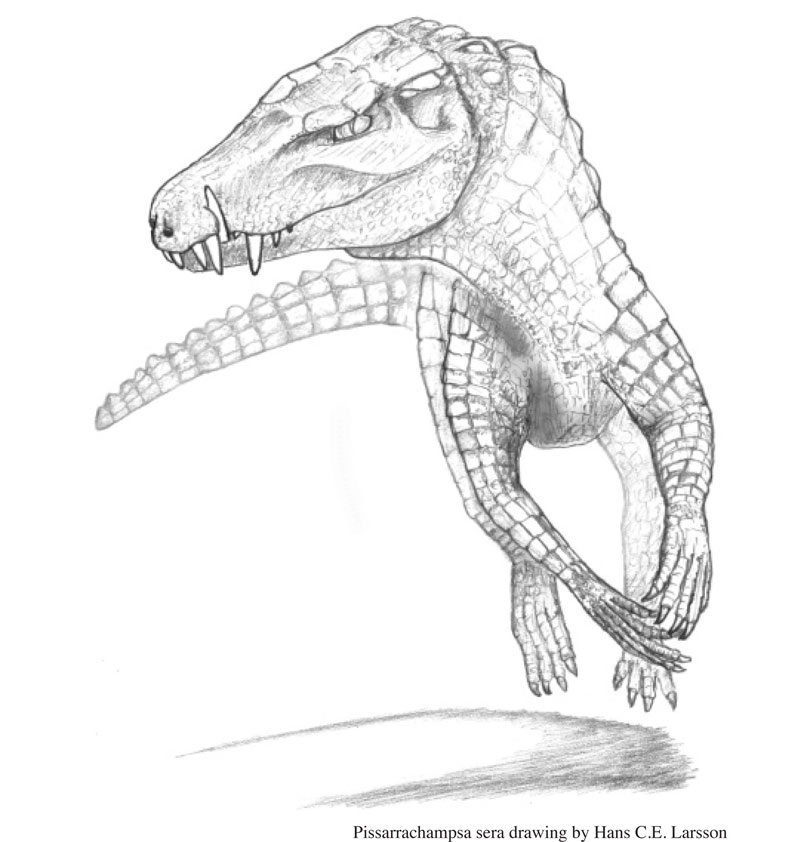

The creature is named Pissarrachampsa sera. Pissarrachampsa means "a crocodile from piçarra," the local name for fossil-bearing sandstones, and sera means "late," referring to how it was one of the last fossils found during the 2008 expedition that uncovered it. It also refers to the local flag that quotes Virgil — "Libertas Quae Sera Tamen" — meaning "Freedom, Albeit Late."

This croc almost certainly did not lurk like a log in a river like its modern relatives. "The rocks from the outcrop where we found the fossils, as well as those from other related areas, suggest a hot and considerably dry environment for the region dating back 70 million years," researcher Felipe Montefeltro, a paleontologist at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, told LiveScience.

Instead, the ecology of the predators was probably similar to that of wild dogs living today, researchers said. Given the number and size of their teeth, the crocs probably fed on animals of about the same 15- to 20-foot (4.5 to 6 meter) size, including dinosaurs and fellow crocs from the region, the researchers say. Rather than clambering over the ground like the crocs we see today, P. sera would have galloped on long limbs.

Similar to other crocodilians of its era, this croc had plated armor, roughened bone surfaces and massive attachments for jaw-closing muscles. Still, the baurusuchid lineage of crocodilians this new fossil belongs to is known for many unique anatomical features, such as unusually large canine teeth, forward-facing nostrils and tall, thin skulls.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We are dealing with an exceptionally divergent lineage of extinct crocodile diversity," Montefeltro said. "There are many fossils that still need to be found to link this crocodile to those who came before and after."

A digital reconstruction of the fossil's brain cavity is in the works and is revealing information on the creature's brain size and shape, and hearing abilities. Those results will be presented in the fall at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual meeting. The researchers will also look at the rest of P. sera's internal structures in detail "to find clues about how this crocodile lived and why it is so peculiar," Montefeltro said.

The scientists detailed their findings online July 13 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.