NASA First Invaded Red Planet with Viking Mars Landing

On Mars Day every year, people celebrate the first spacecraft to successfully land on Mars — NASA's Viking 1, which touched down on the Red Planet 35 years ago.

The craft that landed July 20, 1976, the first of many visitors to Mars, had been designed to work for 90 days, but it continued gathering data for more than six years. In doing so, Viking 1 helped answer many questions about the nature of Earth's neighbor, but it also left behind a mystery that remains tantalizingly unsolved to this very day: Is there evidence of life on Mars?

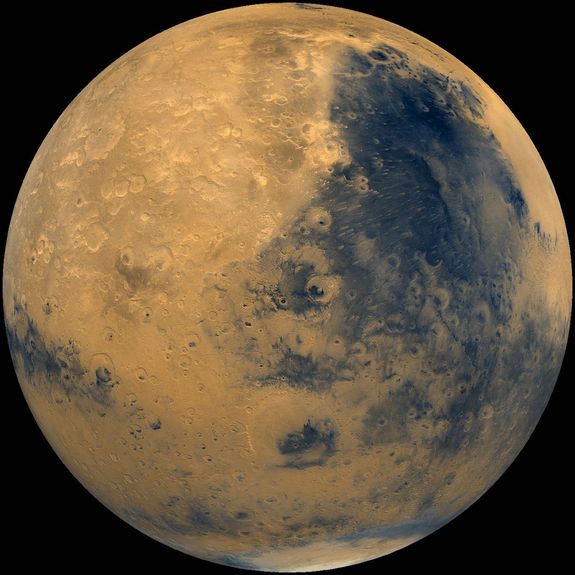

Before Viking 1 arrived, scientists had no high-resolution images of the Martian surface. The mission helped image the entire surface of Mars at a resolution of about 500 to 1,000 feet (150 to 300 meters), with selected areas at about 25 feet (8 m).

This provided a more complete view of the planet than scientists had ever had, showing volcanoes, lava plains, giant canyons, craters and wind-formed features. [Mars Photos by Rovers Spirit and Opportunity]

The Martian air and surface

Viking 1, along with Viking 2, also provided the first measurements of the atmosphere and surface.

"By digging up Martian soil, the Viking landers found out they were several percent water by weight," said Robert Zubrin, president and founder of the Mars Society.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Of course, this was an underestimate, which was known about even then — the soil was made to sit in 15 degrees C temperatures [59 degrees F] before it was properly sampled, so it lost some water. Still, it showed Martian soil was several percent water, as opposed to several parts per million water as is the case with lunar soil. This greatly reinforced the picture greatly suggested by Mariner 9 that Mars was covered with innumerable systems of dry riverbeds."

Looking for life

Viking also represented the first and so far only attempt to search for life on Mars. Its findings are hotly debated today.

"One school of thought, exemplified by Gil Levin, made the cause for life, while the other from Norm Horowitz argued against it on Mars," Zubrin said. "The Viking experiments remain inconclusive."

The landers had detected organic molecules such as methyl chloride and dichloromethane. However, these compounds were dismissed as terrestrial contamination — namely, cleaning fluids used to prepare the spacecraft when it was still on Earth.

"The real question of Mars is about life, and to answer it we'll need people there," Zubrin said. "If one thinks the laws of science of life on Earth are the same elsewhere in the universe — which I do — then it's rational to believe that life once developed on Mars when it was a warm and wet planet. There may now be fossils on the surface and maybe living organisms underground."

He added: "The question that a human mission to Mars could resolve is whether the origin of life is a high-probability event that occurs in a natural sequence of chemical complexification. If that's the case, then life should have appeared on Mars and life is extremely abundant in the universe. If not, then we could be unique. Mars is a Rosetta stone for understanding the potential and diversity of life in the cosmos."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.