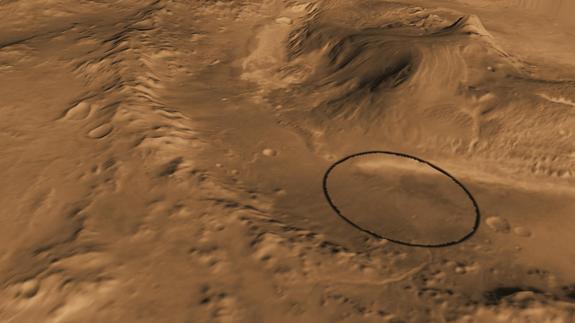

NASA's next Mars rover, the car-size Curiosity, is slated to land in a huge crater called Gale in August 2012. If life ever existed at Gale, will Curiosity detect it?

Probably not, at least not directly. The one-ton rover — the centerpiece of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission — wasn't designed to search for signs of life. Rather, its main task is to assess whether Gale contains, or ever did contain, the specific ingredients that would make it capable of supporting microbial life.

That's a subtle but important difference.

"Let me emphasize that we are not a life-detection mission," John Grotzinger, MSL project scientist at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., told reporters today (July 22). "We cannot look for fossils, microbial fossils, of any type."

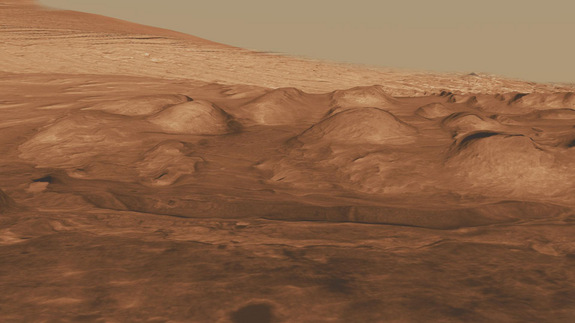

Studying a huge sediment mound

What Curiosity will be doing is studying the many rock layers in Gale Crater, which boasts a huge sediment mound rising 3 miles (5 kilometers) into the Martian sky. Those layers preserve a record of changing environmental conditions on Mars spanning many millions of years.

The rover will read those layers like a history book, scientists said. [Gale Crater FAQ: Mars Landing Spot for Next Rover Explained]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That will give us a history of some of the ancient environments on Mars, how those changed and help us evaluate the habitability of the planet," said rover science team member Dawn Sumner, a geologist at the University of California, Davis.

Gale is known to harbor clays and sulfates, which form in liquid water. That's a promising (but not sufficient) indicator of possible habitability. Other key components of habitability include an energy source to support metabolism, as well as a source of carbon, Grotzinger said. [What Are the Ingredients of Life?]

Carbon compounds — also known as organics — form the building blocks of life on Earth, the only life we know of.

Looking for organics

So part of Curiosity's mission involves scouring Gale for any signs of carbon-based compounds. Organics present in loose sediments often get destroyed when those sediments are compressed into rock, Grotzinger said. So even if Gale once did harbor organics, Curiosity may have a tough time finding them.

"On a planet that teems with life, on Earth, we almost never see organic carbon preserved," Grotzinger said. "But it does happen. And so we hope to be able to look for organic carbon."

Finding convincing evidence of organics would mark a big step forward in the search for life on Mars (NASA's Viking landers found equivocal evidence of carbon compounds in Martian soil in the 1970s). But even if Curiosity finds organic molecules, it wouldn't guarantee that the Red Planet ever hosted life, because not all organics have a biological origin.

The compounds are widespread throughout the solar system. They seem to be common, for example, on asteroids, comets and the icy bodies orbiting the sun in the faraway Kuiper Belt.

So if Curiosity finds organics, the discovery would open a new — and doubtless lively — round of debate about Martian life.

"I expect that we'll have an exciting time trying to determine if there is any evidence for biological activity in the organics we find," astrobiologist Chris McKay, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., told SPACE.com. "The alternative is that the organics might be simply due to meteorite infall."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.