Forecasters Call for New Hurricane Classification

Forecasters are calling for a new system to predict a hurricane’s damage potential, one that could have saved lives taken by Hurricane Katrina and that would be based on the storm’s size and reach, not just its wind speed and push.

Currently, hurricanes are classified with the Saffir-Simpson scale, which gives them a 1 to 5 rating based on the strength of a storm’s winds, the pressure at the center of the storm (also called it’s eye) and the amount of ocean water the storm’s winds push on shore, called storm surge. (A Category 1 hurricane’s winds blow at 74 to 95 mph and Category 5 storms rage faster than 150 mph.)

But these factors don’t always give the full picture of how violent and destructive a storm will be, researchers say, pointing out that the area of a storm and how far out from its center the strong winds reach also influence the amount of damage it can do.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale has been a very valuable tool in warning people about hurricanes,” said engineer Timothy Reinhold of the Institute for Business & Home Safety, a non-profit agency that does research aimed at reducing the social and economic effects of natural disasters. “But we have known for some time that the level of surge and surge-related damage is not well correlated with the maximum wind speeds at landfall.”

Reinhold is also a former deputy director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Case-in-point

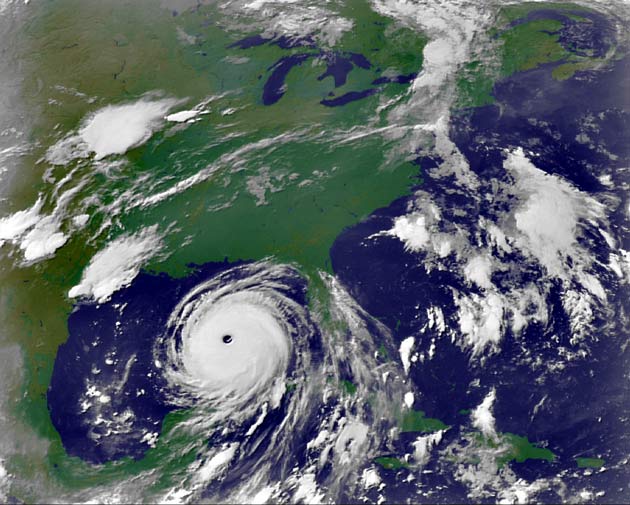

A prime example of this problem, the researchers say, is Hurricane Katrina: Katrina was a Category 5 just 24 hours before landfall, but downshifted to a 3 by the time it touched Gulf shores. In comparison, Hurricane Camille, which devastated the same area in 1969, killing 259 people and causing nearly $1.5 billion dollars in damage, had much stronger winds than Katrina. But Katrina’s wind field extended over a much wider area and caused much more significant coastal flooding, making it the costliest and deadliest hurricane in United States history, taking nearly 2000 lives and causing $81 billion in damage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many Mississippi residents may have relied on their memory of Camille in their decision not to evacuate, the researchers argue, and call for a new Hurricane Destructive Potential classification tat could better alert coastal resident’s to a storm’s potential for damage.

“By incorporating both size and intensity, I see this system as a better way to allow people to assess the true potential impact of an approaching storm,” said Mark Powell, a meteorologist with the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory in Miami. “If people knew that Katrina had a much higher damage potential than Camille, then Mississippi residents who chose to stay might have evacuated.”

Hurricane season begins on June 1 and ends on November 30, though Subtropical Storm Andrea jump-started the season on May 9.

Powell and Reinhold plan to test their new classification system, detailed in the April issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, during the 2007 season, which is predicted to be an active one.

- 2007 Hurricane Guide

- Natural Disasters: Top 10 U.S. Threats

- Images: Hurricane Katrina

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.