Deep-Sea Alien Abode Discovered

Carnivorous sponges, blind creepy-crawlies adorned with hairy antennae and ribbed worms are just some of the new characters recently found to inhabit the dark abysses of the Southern Ocean, an alien abode once thought devoid of such life. Recent expeditions have uncloaked this polar region, finding nearly 600 organisms never described before and challenging some assumptions that deep-sea biodiversity is depressed. The findings also suggest that all of Earth's marine life originated in Antarctic waters. Scientists had assumed that the deep sea of the South Pole would follow similar trends in biodiversity documented for the Arctic. “There are less species in the Arctic than around the equator,” said one of the study scientists, Brigitte Ebbe, a taxonomist at the German Center for Marine Biodiversity Research. “People assumed that it would be the same if you went from the equator south, but it didn’t prove to be true at all.” The findings, reported this week in the journal Nature, provide a more accurate picture of creatures in the southern deep sea and shed light on the evolution of biodiversity in the deep ocean, including ancient colonization dating back 65 million years. "The Antarctic deep sea is potentially the cradle of life of the global marine species,” said lead author Angelika Brandt of the Zoological Institute and Zoological Museum at the University of Hamburg. Deep dwellers Between 2002 and 2005, an international team of scientists completed three research expeditions to the Weddell Sea aboard the German vessel Polarstern. Part of the Southern Ocean, the Weddell Sea is bounded by an Antarctic bulge called Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. Ernest Shackleton's Endurance was trapped and crushed by ice in this sea in 1915. (Shackleton and his entire crew survived. Shackleton died in 1922 of a heart attack on a different Antarctic expedition). Part of the ANDEEP (Antarctic benthic deep-sea biodiversity) project, the team collected biological samples from regions between about 2,000 and 21,000 feet below the surface of the Weddell Sea and nearby areas. In addition to cataloging biodiversity, the scientists aimed to determine how species intermingled within and between the deep and shallower waters and whether continental-shelf organisms colonized the deep ocean or vice versa. The Weddell Sea is part of a vast ocean current and a critical source of deep water and possibly a mode of transport to the rest of the Southern Ocean. Some of the scientists' findings indicate species originating in a single water domain did migrate to the Southern Ocean, and some even trekked across the globe and now inhabit the Arctic waters. Many of the organisms have relatives in both the nearby shallower waters and even in other ocean basins. Species finds included 674 species of isopods, a group of crustaceans, 80 percent of which were new to science. Some of the isopods and marine worms spotted on the continental shelf sported clues of their deep-water past. “On the shelf, the animals have eyes because they can see. There’s light in the water. In the deep sea you don’t really need them, so many animals get rid of their eyes,” Ebbe told LiveScience. “There were some [species] that are very closely related to eyeless isopods, and they are now living on the shelf. So that’s an indication they have moved upward,” Ebbe said. Water travel Many species living in the deep abyss of the Weddell Sea showed strong links with other oceans, particularly organisms like amoeba that can disperse their larvae over long distances. Poor dispersers—including some isopods, nematode worms and seed shrimps—stayed close to home in the Southern Ocean. One particularly cosmopolitan group included the foraminifera, or tiny single-celled organisms covered with relatively decorative shells. Genetic analyses showed that three foraminifera species (Epistominella exigua, Cibicidoides wuellerstorfi and Oridorsalis umbonatus) found in both the Weddell Sea and the Arctic Ocean, were nearly identical. “They literally found some of [the foraminifera] from pole to pole, which is really amazing,” Ebbe said. Time to diversify In terms of the soaring biodiversity, the scientists suggest organisms in the Antarctic have been around for a long time, giving them time to diversify. “The Southern Ocean has been like it is pretty much for the last 40 million years, and it has been isolated,” Ebbe said. “So the communities have had a long, long time to evolve. In the Arctic, it is much different.” In the geologic past Antarctica belonged to a giant land mass called Gondwana that straddled the equator. The land mass, which also included Africa, Australia, India and the tip of South America, started breaking apart more than 100 million years ago. About 60 million years ago, Antarctica had drifted close to the South Pole, and oceans filled the gaps between Antarctica and Africa and India. By 40 million years ago, the continent had become completely encircled by water, now called the Southern Ocean. "What was once thought to be a featureless abyss is in fact a dynamic, variable and biologically rich environment,” said a study team member Katrin Linse, a marine biologist with the British Antarctic Survey. “Finding this extraordinary treasure trove of marine life is our first step to understanding the complex relationships between the deep ocean and distribution of marine life," she said.

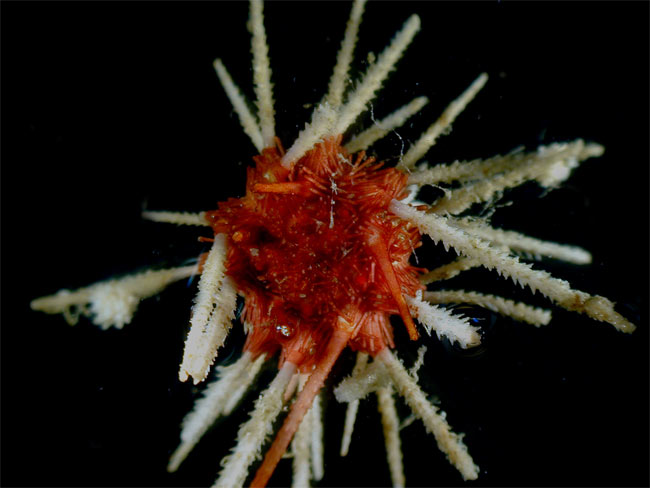

- Images: Alien Life of the Antarctic

- Video: Under Antarctic Ice

- Strange New Creatures Found in Antarctica

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.