Moonless Earth Could Potentially Still Support Life, Study Finds

Scientists have long believed that, without our moon, the tilt of the Earth would shift greatly over time, from zero degrees, where the Sun remains over the equator, to 85 degrees, where the Sun shines almost directly above one of the poles.

A planet's stability has an effect on the development of life. A planet see-sawing back and forth on its axis as it orbits the sun would experience wide fluctuations in climate, which then could potentially affect the evolution of complex life.

However, new simulations show that, even without a moon, the tilt of Earth's axis — known as its obliquity — would vary only about 10 degrees. The influence of other planets in the solar system could have kept a moonless Earth stable. [10 Coolest New Moon Discoveries]

The stabilizing effect that our large moon has on Earth's rotation therefore may not be as crucial for life as previously believed, according to a paper by Jason Barnes of the University of Idaho and colleagues which was presented at a recent meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

The new research also suggests that moons are not needed for other planets in the universe to be potentially habitable.

As the world turns

Due to the gravitational pull of its star, the axis of a planet rotates like a child's top over tens of thousands of years. Although the center of gravity remains constant, the direction of the tilt moves over time, or precesses (as astronomers call it).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Similarly, a planet's orbital plane also precesses. When the two are in synch, the combination can cause the total obliquity of the planet to swing chaotically. But the gravity of Earth's moon has been shown to provide a stabilizing effect. By speeding up Earth's rotational precession and keeping it out of synch with the precession of Earth's orbit, it minimizes fluctuations, creating a more stable system.

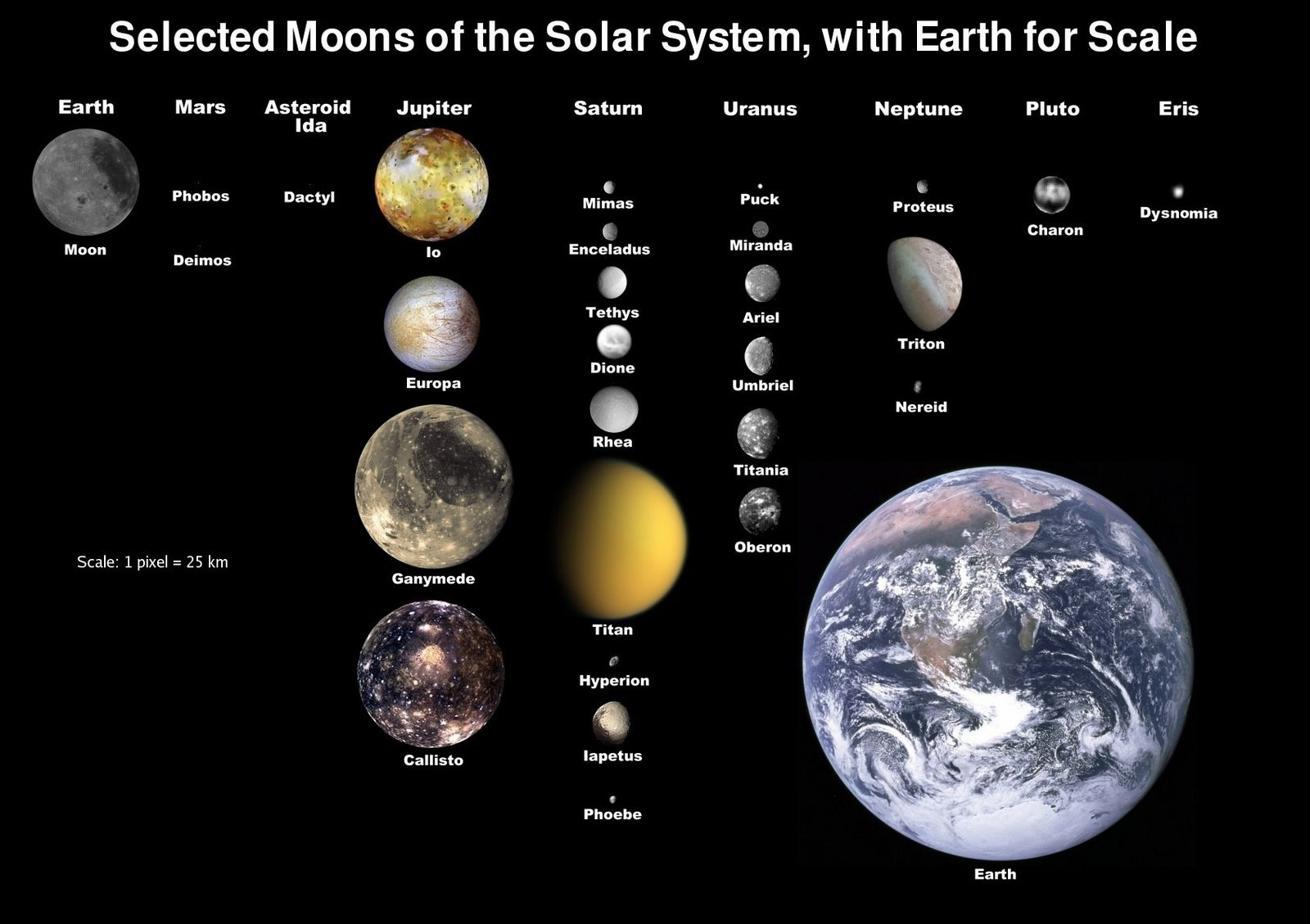

As terrestrial moons go, Earth's moon is on the large size — only about a hundred times smaller than its parent planet. In comparison, Mars is over 60 million times more massive than its largest moon, Phobos.

The difference is substantial, and with good cause — while the Martian moons appear to be captured asteroids, scientists think that Earth's moon formed when a Mars-sized body crashed into the young planet, blowing out pieces that later consolidated as the lunar satellite — a satellite which affects the planet's tilt.

Scientists estimate that only one percent of any terrestrial planets will have a substantial moon. This means that most such planets are expected to experience massive changes in their obliquity.

The pull of the planets

While Earth's moon does provide some stability, the new data reveals that the pull of other planets orbiting the sun — especially Jupiter — would keep Earth from swinging too wildly, despite its chaotic evolution. [10 Extreme Planet Facts]

"Because Jupiter is the most massive, it really defines the average plane of the solar system," said Barnes.

Without a moon, Barnes and his collaborators have determined that Earth's obliquity would only vary 10 to 20 degrees over a half a billion years.

That doesn't sound like much, but the changes of 1 to 2 degrees the planet presently exhibits are thought to be partly responsible for the Ice Ages.

According to Barnes, the present shift is "a small effect, but in combination with Earth's present climate, it causes big changes."

Still, a 10-degree change is not a huge problem when it comes to life. "(It) would have effects, but not preclude the development of large scale, intelligent life."

Furthermore, if Jupiter were closer, Barnes explains, the Earth's orbit would precess faster, and the moon would actually make the planet fluctuate more wildly, rather than less.

"A moon can be stabilizing or destabilizing, depending on what's going on in the rest of the system," he said.

The benefit of a backspin

The team also determined that planets with a retrograde, or backward, motion should have smaller variations than those that spin in the same direction as their parent star, a large moon notwithstanding.

"We think the initial rotation direction should be random," Barnes said. "If it is, half the planets out there would not have problems with obliquity variations."

What determines which way a planet spins? He suspects that "whatever smacks the planet last establishes its rotation rate."

A 50/50 shot at retrograde precession, combined with the likelihood of other planets in the system keeping the planet from tipping on its side, means more terrestrial planets could be potentially habitable. Barnes ventured an estimate that at least 75 percent of the rocky planets in the habitable zone may be stable enough for life to evolve, though he notes that additional studies are needed to confirm or disprove that.

In comparison, the previous idea that a large moon was necessary for a constant tilt meant that only about 1 percent of terrestrial planets would have a steady climate.

"A large moon can stabilize (a planet)," Barnes said, "but in most cases, it's not needed."

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.