Where the Sun Don't Shine, Mussels Munch on Hydrogen

Deep-sea mussels use on-board bacterial "fuel cells" to harness energy from hydrogen spewing out of hydrothermal vents, according to research indicating that the use of this alternative fuel may be widespread in the communities at these vents. This is the first identified deep-sea organism to use hydrogen as fuel.

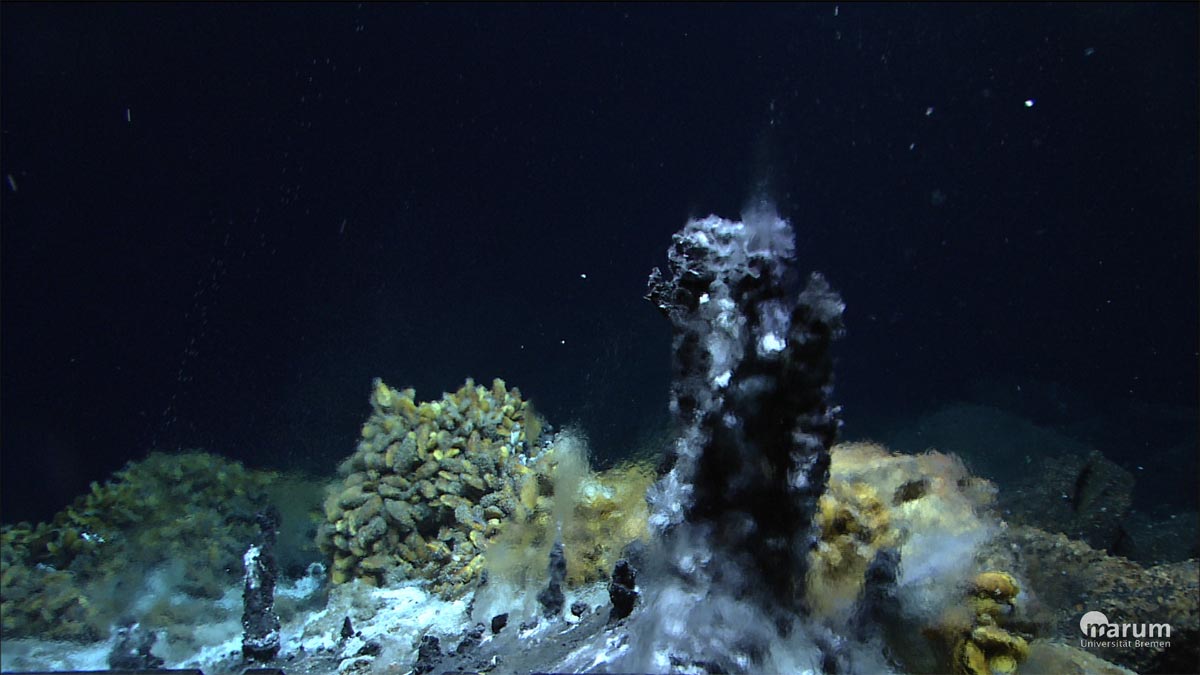

Hydrothermal vents occur where super-heated water, laden with dissolved minerals from the Earth's crust, gushes into the ocean, at temperatures as hot as 752 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius). When the heated material hits the cold deep-sea water, it forms so-called black smoker chimneys.

Inhospitable as this hot, deep, dark environment may sound, it is home to animals such as worms, mollusks and crustaceans. Their survival depends on symbiotic bacteria that harness energy from dissolved compounds released by the vents to create sugars, which the organisms can then eat. Plants do something similar, using energy from the sun to create sugars, a process called photosynthesis.

Hydrogen is the third alternative energy source discovered in these communities. Until now, the bacterial symbionts were known to use only sulfur compounds and methane. (Symbionts are organisms that depend on each other for survival.)

A series of expeditions to the Logatchev hydrothermal vent field, 9,843 feet (3,000 meters) underwater on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, halfway between the Caribbean and the Cape Verde Islands, recorded the highest hydrogen concentrations ever measured at hydrothermal vents. [Video: Deep Ocean Springs Full of Life]

Researchers then sent two remotely operated deep-sea submersibles to sample mussels called Bathymodiolus puteoserpentis. These mussels are one of the most abundant animals at Logatchev; their beds contain an estimated half a million members, and their gills contain multiple symbionts. One of these, the researchers found, is capable of using hydrogen as an energy source.

The mussels' symbionts have a gene that codes for an enzyme crucial to the process. Symbionts of other vent inhabitants, including tube worms and shrimp, have the same gene.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We propose that the ability to use hydrogen as an energy source is widespread in hydrothermal vent symbioses, particularly at sites where hydrogen is abundant," the authors conclude in the Aug. 11 issue of the journal Nature.

The international team was led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, the Helmhotz Centre for Environmental Research and the University of Bremen, all in Germany.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.