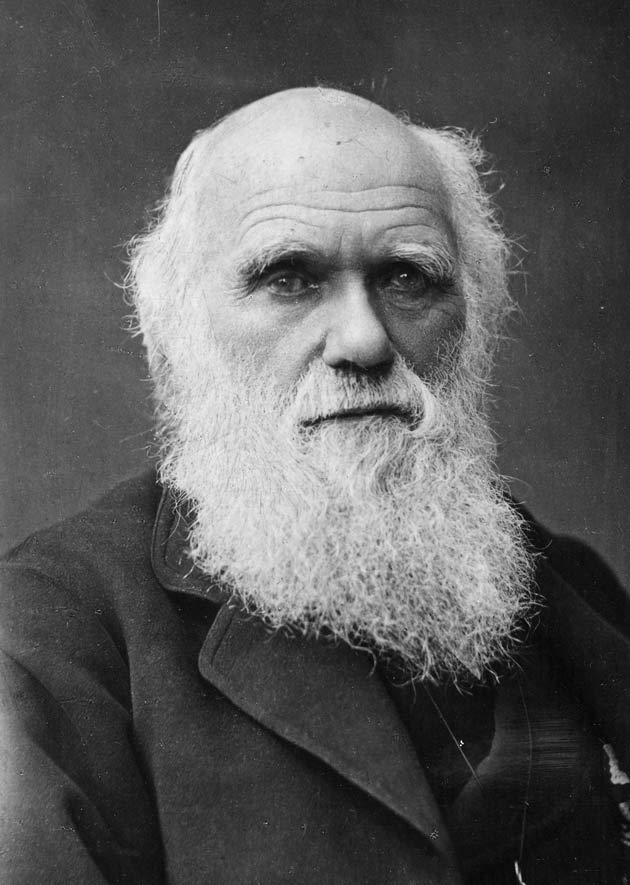

Before Charles Darwin's squeamish stomach forced him to quit medical school, before sailing aboard the HMS Beagle and before penning his masterwork “The Origin of Species,” the future father of evolutionary theory was a child who had bad spelling and stinky feet. "I only wash my fett [sic] once a month at school, which I confess is nasty, but I cannot help it, for we have nothing to do it with," a 12-year-old Darwin wrote to a friend. In another letter, an older Darwin expresses a naïve excitement about the upcoming voyage that will change his life and biology forever: “The scheme is a most magnificent one. We spend about 2 years in S America, the rest of time larking round the world.” These and other insights about the man who came up with the theory of evolution by natural selection can now be gleaned by the public in letters that are being made available online for the first time. The website contains summaries of more than 14,700 letters written both by and to the famous naturalist, with full transcriptions available for many of them. It is part of the ambitious Darwin Correspondence Project, which aims to publish all of the letters as books. When complete, the letters will take up an estimated 30 volumes. Prolific letter writer “The Correspondence Project started in 1974, and it’s not finished yet,” said project researcher Sam Kuper, of Cambridge University in England. “So far, letters up to 1867 have been published, and we’re currently working on a volume of letters from 1868. But Darwin lived until 1882, so there are many letters that remain to be published.” Darwin corresponded with nearly 2,000 people during his lifetime. Besides family and scientists, Darwin also wrote to diplomats, clergymen, gardeners and pigeon breeders. Letters played an important role in the development of his scientific ideas. “For much of his life, Darwin was something of an invalid and lived in his house in Kent,” Kuper told LiveScience. To acquire information difficult for him to gather personally, Darwin wrote to people who could make observations on his behalf. “He used his correspondents as his eyes and ears as he was developing his theories,” Kuper said. More than just a scientist In one letter to his friend J.D. Hooker, an English botanist who urged Darwin to make public his evolutionary theory, he admits that his theory about the immutability of species “is like confessing a murder.” In a letter to Alfred Russel Wallace, a young naturalist who formulated a theory remarkably similar to his own, Darwin writes: “I agree to the truth of almost every word of your paper & I daresay that you will agree with me that it is very rare to find oneself agreeing pretty closely with any theoretical paper; for it is lamentable how each man draws his own different conclusions from the very same fact.” Reading the letters, one gets a sense of not only Darwin the scientist, but also Darwin the friend, husband and father. Perhaps reminded of the death of his own daughter, Anne, Darwin grieved when he heard that Hooker’s son had contracted scarlet fever. “My poor dear old friend you are most unfortunate. The tide must turn soon … Much love much trial, but what an utter desert is life without love.” A letter by Darwin's wife, Emma, expresses her concern that he will lose his faith in God, which he eventually does. “May not the habit in scientific pursuits of believing nothing till it is proved, influence your mind too much in other things which cannot be proved in the same way, & which if true are likely to be above our comprehension,” she writes. The letters reveal a much more gregarious and modest man than textbooks might suggest. “The common perception of Darwin is that he is a sort of cold scientist that came up with this theory of nature, red in tooth in claw, and he seems a bit of a brutal character,” Kuper said, “but the correspondence reveals he is anything but that.”

- An Ambiguous Assault on Evolution

- The Life of Charles Darwin: From Aimless Adventure to Tragedy and Discovery

- Image Gallery: Darwin Gallery: Darwin on Display

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus