The Top 5 Benefits of Play

Why play matters

Don't underestimate child's play. It may look like leisure time, but when children are playing house, fighting imaginary dragons or organizing a game of hopscotch, they're actually developing crucial life skills — and preparing their brains for the challenges of adulthood.

The bad news, child development experts say, is that free playtime has been shrinking for children over the past three decades. So check out these five scientific benefits of play, and then break out the tinker toys. Your child's brain might thank you.

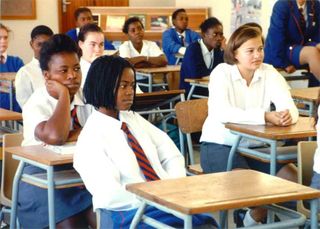

Better behavior

Taking recess away from schoolchildren as punishment might be counterproductive. According to a 2009 study in the journal Pediatrics, kids behave better in the classroom when they have the chance to blow off steam on the playground during the day. Researchers compared teacher ratings of 8- and 9-year-olds' behavior in schools with and without recess periods. The kids who had more than 15 minutes a day of breaks behaved better during academic time. Unfortunately, 30 percent of the more than 10,000 children in the study had no recess or less than 15 minutes of recess each day.

Playing for the team

Play teaches kids to, well, play nice. Research published in the Early Childhood Education Journal in 2007 revealed that both free play and adult-guided play can help preschoolers learn awareness of other people's feelings. Playing also teaches kids to regulate their own emotions, a skill that serves them well as they move through life.

"You get to try things out with no consequences," said Kathy Hirsch-Pasek, a child development psychologist at Temple University, who researches the benefits of play. "[Play] also allows you to wear different hats, to master social rules. That's huge."

Let's move

Tree-climbing, foursquare and even a round of dress-up get kids moving much more than television or computer-game time. The American Heart Association recommends that children over the age of 2 engage in at least an hour a day of moderate, enjoyable physical activity. There's evidence that active children grow into active adults, thus decreasing their risk of heart disease and other scourges of a sedentary lifestyle. One study published in 2005 in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine followed Finnish citizens over 21 years and found that the most active 9- to 18-year-olds later remained highly active later in life.

Learning boost

Reading, 'riting, 'rithmatic and … recess? A 2009 study in the Journal of School Health found that the more physical activity tests children can pass, the more likely they are to do well on academic tests. That suggests unrelenting classroom time may not be the best way to improve test scores and learning, said psychologist Hirsch-Pasek.

"Children learn to count when they're doing hopscotch," Hirsch-Pasek said. "They learn about numbers when they're playing stickball, and believe me they know which team is ahead. They are telling stories on the playground, and they're getting active."

It's fun

All work and no play really does make Jack a dull boy. Play is a natural state of childhood, Hirsch-Pasek said, pointing out that even non-mammals do it. University of Tennessee biopsychologist Gordon Burghardt told The Scientist magazine in 2010 that he's even observed turtles playing.

The joyful properties of play are evident in schools served by the non-profit Playworks, which assigns research "coaches" to schools to teach classic playground games and mentor children in the art of running their own recess. Playworks focuses on low-income school districts, where kids are at high risk of dropping out before high-school graduation.

"We find that kids feel safer," after Playworks helps facilitate recess, said spokesperson Cindy Wilson. "Kids tell us they're more likely to come to school."

Not only that, but recess extends the same freedom to children that adults may take for granted.

"Adults get breaks," Wilson said. "Kids need breaks, too."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.