New Uses Proposed for Old Drugs

With a new matchmaking computer program, researchers may have found a faster way to bring drugs to patients. The program predicts which drugs already on the market could be repurposed for treating other diseases.

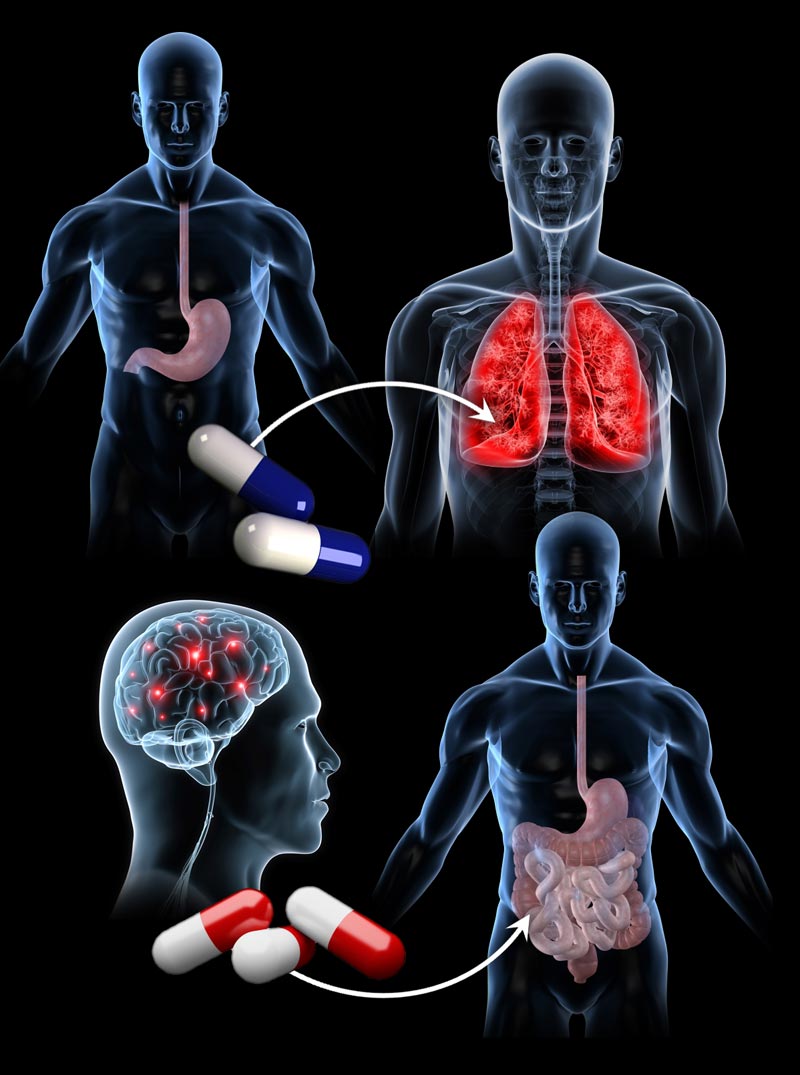

The new study, published today in the online issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine, found, for instance, that drugs used to treat ulcers and seizures could be repurposed for lung cancer and inflammatory bowel disease treatments, respectively.

The results owe their success to computer power and public databases of genomic information. Led by Atul Butte, a bioinformatics researcher at Stanford University and supported by the National Institutes of Health, the team uncovered promising drug treatments for 53 human diseases ranging from cancers to Crohn's disease and cardiovascular conditions.

"Many other uses of drugs remain to be discovered," Butte said, "and computational methods applied to public molecular data can help with finding these new uses."

Trimming time

Developing a new drug and bringing it to market can take 15 years and cost over $1 billion. Identifying ways to put FDA-approved drugs to new uses, called drug repositioning, lets researchers sidestep another long and costly path through testing. It also means that people who need drug therapies don't have to wait as long for them.

Butte and his team started by digging through computerized public databases to see how 100 diseases alter the activity of thousands of genes. For example, when compared with healthy cells, a disease might increase the activity of genes A, B and C, and decrease the activity of genes D, E and F. They called this pattern of activity a genetic signature.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers took a similar approach to 164 different drugs, characterizing each with a genetic signature based on activity patterns in human cell samples that had been treated with the drug.

Finally, the team created a computer program to compare the drug and disease signatures. "We developed a computational method to match up molecular data on drugs and diseases, so that when statistically paired up, we can infer that a drug might work against a disease," Butte explained.

Match maker

If a drug signature and a disease signature showed exactly the same pattern of genetic activity, the computer gave the pair a similarity score of +1. If their signatures were completely opposite, the pair received a score of -1.

Because an effective drug theoretically reverses the activity in a diseased cell, opposing signatures (scores closer to -1) indicated a better potential match for treatment.

The end result was a ranked list of potential therapeutics, where 53 of the diseases were significantly matched to drug candidates. Many of the matches confirmed relationships that were already known. For example, the steroid prednisolone is commonly given to treat inflammatory bowel disease; the two had opposing scores in Butte's analysis, making them a good therapeutic match.

But the study also turned up some surprising results. For instance, topiramate, an anticonvulsant used to treat epilepsy, emerged as a better match for inflammatory bowel disease than prednisolone. Another surprising connection appeared between cimetidine, an anti-ulcer drug, and the lung cancer adenocarcinoma.

Experimental evidence

To put their findings to the test, Butte's team conducted experiments using cimetidine to treat adenocarcinoma and topiramate to treat inflammatory bowel disease.

"We show that these two drugs actually do show signs of efficacy when tested on rat and mouse models for these two diseases," Butte said.

In the lab, the researchers found that human lung cancer cells treated with cimetidine in Petri dishes grew slower than untreated cells. In mouse models, increasing doses of the inexpensive anti-ulcer drug also slowed tumor growth.

When Butte and colleagues tested topiramate in rat models of inflammatory bowel disease, they found that the drug reduced swelling and damage to colon tissue — sometimes more than prednisolone.

Even though more studies are needed to see if the same trends are true in humans, Butte's outside-the-box approach to drug discovery could potentially be applied to treat a range of diseases in unanticipated ways. It also highlights the value of computational analysis and public databases to learn more about how diseases and drugs work at the molecular level.

"This work is still at an early stage," said Rochelle Long of the National Institutes of Health, which partly funded the research. "But it is a promising proof of principle for a creative, fast and affordable approach to discovering new uses for drugs we already have in our therapeutic arsenal."

Learn more:

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.