For the first time, scientists have watched the evolution of a huge solar storm, from its origin on the sun until its collision with Earth 93 million miles later.

The unprecedented look at a coronal mass ejection (CME), revealed today (Aug. 18) during a NASA press conference, should help researchers better understand how solar storms evolve as they barrel toward our planet. And that, in turn, should improve space weather forecasts, giving us more time to prepare for potentially damaging impacts, researchers said.

"It's a big advance," Alysha Reinard, of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center, told reporters today. "Now we're actually seeing the CME moving across the sky. It's amazing to see, and it really helps our predictions." [Watch the NASA sun storm video]

Tracking a solar storm

CMEs are billion-ton clouds of solar plasma ejected from the sun at speeds up to 3 million mph (5 million kph). CMEs that hit Earth can wreak havoc on our planet, causing disruptions in GPS signals, radio communications and power grids. [Worst Solar Storms in History]

Scientists have seen CMEs erupt before, but they've generally only gotten head-on looks at the storms as they plow into Earth — until now.

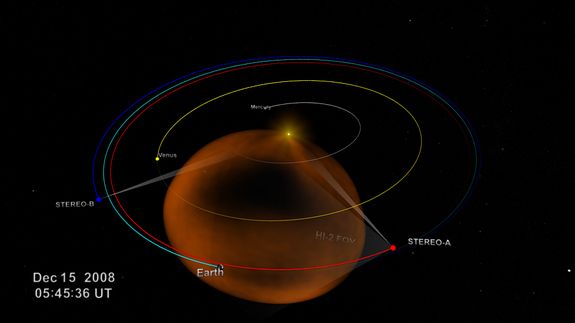

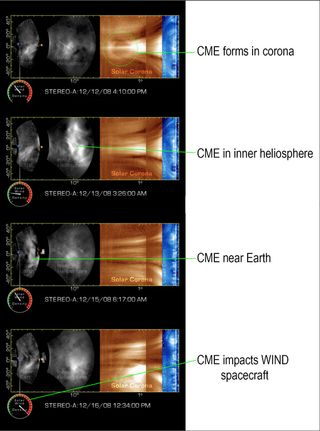

NASA's Stereo-A spacecraft watched as a huge CME erupted back in December 2008. Stereo-A orbits the sun substantially ahead of our home planet, so it was able to watch the cloud shift and change as it moved through space toward Earth. (The spacecraft's twin, Stereo-B, lags behind the Earth in its orbit.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And shift and change it did. The video shows the CME scooping up solar wind particles on its path out from the sun, morphing into a towering wall of plasma by the time it neared our planet.

The video allowed researchers to determine key characteristics of the CME. They could pinpoint its precise arrival time at Earth, for example. And by measuring the cloud's brightness, scientists were able to nail down its mass.

A tough measurement

The video, made using Stereo-A's five cameras, didn't beam down to Earth in ready-to-watch format.

CMEs are extremely bright soon after they erupt, but once they make it out into space, they become very hard to track. By the time a typical CME reaches the orbit of Venus, for example, it's one billion times fainter than the surface of the full moon, researchers said.

So scientists worked hard for several years processing Stereo-A's observations into a watchable video.

"This is an extraordinarily difficult extraction problem," said Craig DeForest of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. "A tremendous amount of extraordinarily careful work was needed to develop the algorithms."

Now that they've got the technique down, though, it shouldn't take nearly as long to extract video of other CMEs, researchers said.

And that should help scientists better understand what CMEs will look like when they slam into Earth — and when exactly they will do so.

"In the past, our very best predictions of CME arrival times had uncertainties of plus or minus 4 hours," Reinhard said in a statement. "The kind of movies we've seen today could significantly reduce the error bars."

The new results also complement another key advance in solar-storm prediction also announced today. Scientists have found a way to identify active regions of the sun below the solar surface a full day or two before they erupt as sunspots.

"It is a really dynamic time in the history of heliophysics," said Madhulika Guhathakurta, Stereo program scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.