'Missing' Lager Brewing Yeast Discovered in Patagonia

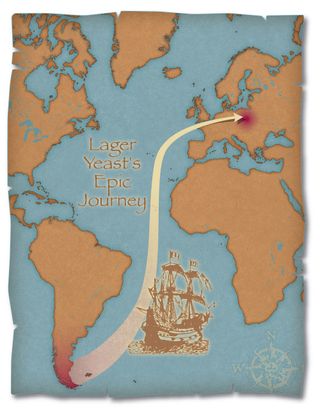

A fruit fly's journey from Patagonia to Bavaria could be the reason we enjoy nice, cold-brewed lager beers today. The missing parent of the hybrid yeast used for brewing lagers has just been discovered in Patagonia.

Until now, scientists had known lager beers were made from a hybrid yeast, with half of its genes coming from a common ale yeast and the other half coming from an unknown species.

"Nothing they could find in the wild or in the freezer collections could match the missing component of the lager yeast," study researcher Chris Todd Hittinger at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told LiveScience. [Raise Your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts]

Genes from the new species could be used to design better beer-brewing yeasts. "Those might be prime candidates you might want to hit by genetic engineering," Hittinger said. "You can imagine an age of designer yeasts."

Missing link

They found the missing yeast growing on southern beech trees in Patagonia. They sequenced the genes and found that this species of yeast was very likely to be a parent of the lager yeast hybrid.

"It’s a 99.5 percent match to the missing half of the lager genome. It's clear that it is this species," Hittinger said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each lager-yeast parent contributed one copy of its genome to the special yeast through sexual reproduction. The resulting yeast hybrids are sterile, meaning they can't reproduce sexually, but they can make direct copies of themselves and expand their genetically identical population.

In nature, this wouldn't be a smart evolutionary tactic, because it doesn't allow the yeast to adapt to changing conditions, the researchers said; but in the beer-brewing facilities, where temperatures are constant and food is freely available, the yeast can thrive.

Creating new yeasts

The newly discovered species, Saccharomyces eubayanus, has interesting properties, including an ability to grow in colder temperatures. This is how it probably got into the lager-brewing chain, when brewers started storing their beer in caves.

"In the 15th century, the Bavarians started the process of lagering, when they would brew and store their beer in caves or cellars and keep it at a constant cool temperature," Hittinger said. "That changed the rules and created a new yeast."

S. eubayanus could have been carried across the Atlantic on the feet of fruit flies hovering around vats of beers or fruit juice, and its ability to tolerate cold would have made it well suited to brew lagers. It's possible that S. eubayanus could be hiding somewhere in Europe as well, but extensive searching hasn't found it in the wild.

These hybridizations aren't perfect, though, as each species of yeast has some useful and some not-as-useful qualities for beer brewing. "They would have brought along other less desirable traits by accident," Hittinger said. "Having access to the raw genetic material in the wild allows researchers to go back and see if they can get rid of these bad traits."

The study was published today (Aug. 22) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.