Why Virginia Quake Shook Entire Coast

The quake that hit the East Coast on Tuesday afternoon was notable, but not unprecedented, for the eastern half of the country, geoscientists say.

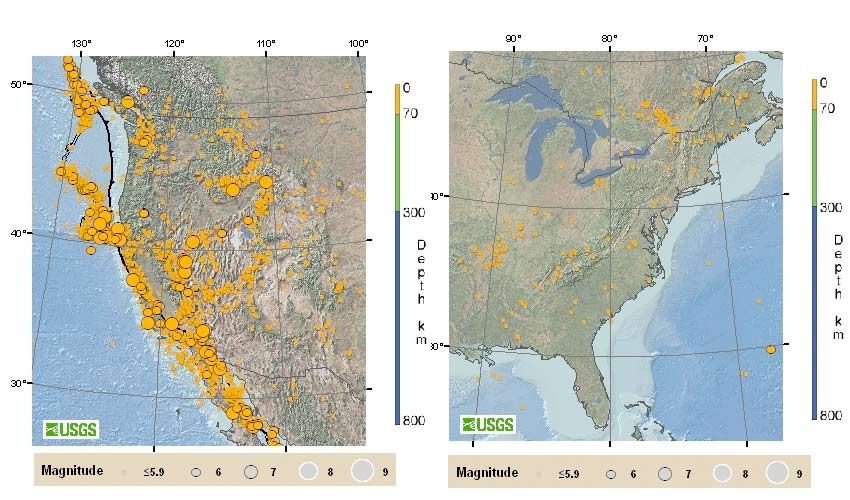

Additionally, the shaking was felt over such a large area — as far south as Atlanta and as far north as Ontario, according to eyewitness reports — largely because the eastern part of the North American continent is different than the West Coast, where quakes are more common. [Album: The Great San Francisco Earthquake]

"The crust is different in the east than in the west," United States Geological Survey (USGS) earthquake geologist David Schwartz told LiveScience. "It's older and colder and denser, and as a result, seismic waves travel much farther in the east than in the west."

Additionally, said Andy Frassetto of the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology, the sediments along the east coast can make quakes feel stronger.

"The sediments of the coastal plain along the eastern seaboard can trap waves as they propagate and produce a minor amplification of the shaking," Frassetto told LiveScience.

A much more extreme version of this effect occurred during the earthquake that hit Christchurch, New Zealand, this year, Frassetto said.

Faults that rupture east of the Rockies usually create quakes felt over more than 10 times the area than those west of the mountains, according to the USGS. A magnitude-5.5 quake in the Eastern U.S. can usually be felt as far as 300 miles (500 km) away.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Latest Shaking

According to the USGS, the 5.8-magnitude quake struck at 1:51 p.m. Eastern Time. The epicenter was 5 miles (8 kilometers) from Mineral, Va., and 84 miles (135 kilometers) away from Washington, D.C. Despite the distance, the Pentagon, the Capitol and other buildings were evacuated. [Read: Large Earthquake Could Strike New York City]

The quake was only about 3.7 miles (6 km) deep, according to the USGS. That's typical for the eastern U.S., Frassetto said. In the east, he said, quakes usually originate in the upper part of the crust.

In contrast, subduction zones such as the Pacific Ring of Fire, where one plate is being pushed under another, produce very deep quakes — sometimes 435 miles (700 km) down, Frassetto said. These super-deep quakes may not even be felt on the surface.

Quakes in the east

Since Virginia lies in the middle of a continental plate, the state doesn't generally experience large-magnitude earthquakes like those that rattle Los Angeles, Alaska, Haiti, Japan and Chile (or any other areas on the edge of a tectonic plate), according to the USGS. Even so, since 1977, there have been about 200 earthquakes in Virginia. The last "big one" in Virginia occurred on May 31, 1897, in Pearisburg; it was a 5.8-magnitude temblor that, in addition to cracking walls and toppling chimneys, reportedly caused a judge in the courthouse there to adjourn a trial, jumping over a railing and fleeing outside, according to the USGS. Virginia is classified as a "moderate" seismic risk, with a 10-20 percent chance of experiencing a 4.75-magnitude earthquake (in quakes above 4.5, buildings begin to fall), the USGS said. Alaska and California take the first and second spots for the most earthquakes in the U.S., respectively, though California experiences more damaging earthquakes due to its greater population and extensive infrastructure.

There is a history of damaging quakes in the eastern United States, however. A destructive quake hit Charleston, S.C., in 1886, damaging thousands of buildings. Its magnitude was probably near 7.0 on the Richter scale. And in 1755, a quake with around a 6.0 magnitude struck off the coast of Massachusetts.

LiveScience Managing Editor Jeanna Bryner contributed to this article.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.