Skinny 'Shrew' Is Oldest True Mammal

A shrew-like animal that snagged insects from ferns lining the shores of freshwater lakes 160 million years ago, might be one of the first "true" mammals to walk the Earth, back when the dinosaurs roamed, a new fossil suggests.

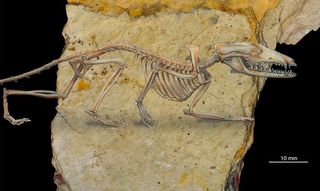

The new fossil, discovered in what is now Liaoning Province in China, is the oldest evidence of the divergence of these "true" or placental mammals from their marsupial counterparts, and indicates the mammalian lineage was evolving faster than expected during the Jurassic Period. [Images of the fossil]

"We can really conclude that the age of placental mammals goes back to over 160 million years ago," study researcher Zhe-Xi Luo, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, told LiveScience. "It's an evolutionary milestone for mammal evolution."

True mammals — those that have taken over much of the world and make up 90 percent of today's mammals — are different from marsupials in several ways. Most importantly, marsupials give birth to very immature babies, which then climb into a pouch on the mother's belly where they feed and grow. Placental mammals stay in the womb for this time, until fully developed.

The new fossil species, now called Juramaia sinensis, included an incomplete skull, partial skeleton and impressions of soft tissue, such as hair.

Even though the soft tissue that would show marsupial or placental traits — mammary glands or a pouch — had not been retained the fossil's forepaw bones and teeth suggested it was closer to placental mammals than marsupials on the mammal family tree. The next-oldest true mammal fossil dates back about 125 million years.

"We are placing this fossil closer to the placental line than the marsupial line, though it is definitely still between the two groups," Luo said. "It's related and part of our ancestry, but it may not be the direct grandmother to our lineage." [Gallery: Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The date this fossil sets for the divergence of placentals and marsupials, 160 million years ago, agrees well with dates garnered from previous genomic analyses.

"This molecular time estimate places the time of split between marsupials and placentals around middle Jurassic, around 165 million years ago," Luo said. "Previously, the oldest record[ed placental fossil] was 125 million years ago, so there was a substantial gap between the fossil record and the molecular estimates."

By pushing back the placental-marsupial division by 35 million years, this fossil shows that even during the age of feathered dinosaurs mammals were expanding and evolving into new groups quicker than previously believed.

The study was published today (Aug. 24) in the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.