How Barrier Islands Survive Storms

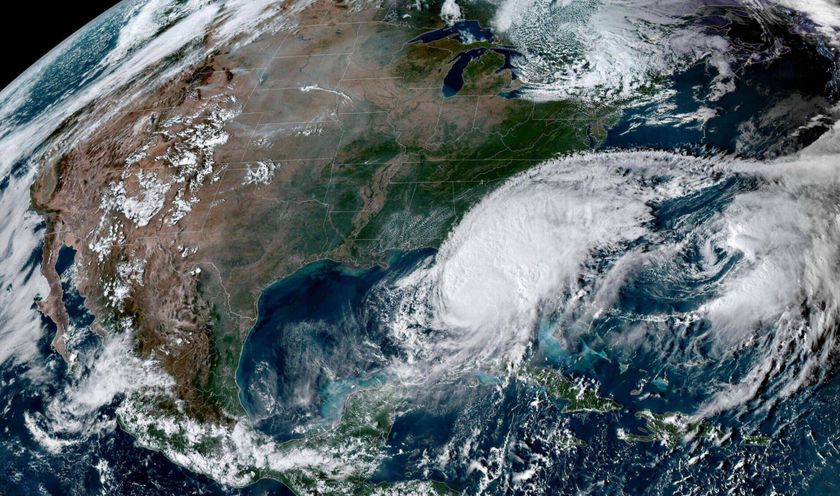

The incoming fury of Hurricane Irene has prompted mandatory evacuations along the Outer Banks of North Carolina. These narrow strips of sand are barrier islands, shaped by thousands of years of waves and tides. Low-lying barrier islands are particularly vulnerable to pounding by storms. Left to their own devices, however, these sandy outposts are surprisingly resilient, geologists say.

"They have ways of protecting themselves," said George Voulgaris, a professor of marine and geological sciences at the University of South Carolina. "Yes, a hurricane will make lots of changes, but the barrier island will recover over time."

Humans can disrupt this process by building on barrier islands, disrupting the natural movement of sand, Voulgaris told LiveScience. [Photos: Beautiful & Ever-Changing Barrier Islands]

Building a barrier

No one is entirely sure how the barrier islands that line the East and Gulf coasts formed. One theory, says Brian Romans, a sedimentary geologist at Virginia Tech, is that the islands accumulate over time from sandbars. Waves break over a submerged sandbar, dropping sand and sediment with each crash, until an island gradually rises out of the ocean.

Another theory is that the islands form from spits of sand originally attached to the mainland. Waves carry sediment parallel to the shore to create these spits, and the connection between spit and shore is later broken by a storm.

"Either way, if the islands persist long enough and vegetation starts to grow on them, that stabilizes them even more," Romans told LiveScience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

According to Voulgaris, the sandbar theory is more likely along the East Coast, because there would have to be a headland protruding off the coast to provide a place for a spit to start growing. You don't see such headlands along the eastern coast, Voulgaris said.

10,000 years of change

The barrier islands along the East Coast are likely no older than 7,000 to 10,000 years, Voulgaris said. Earlier than that, he said, sea levels were rising rapidly as the last ice age ended and glaciers melted. Relatively stable sea levels in the last 7,000 to 10,000 years would have enabled the islands to form.

The islands' size and shape depend on the vagaries of the tides and waves. In South Carolina and Georgia, barrier islands tend to be wide and broken up by tidal inlets, in contrast to North Carolina's long and narrow Outer Banks. The reason, Voulgaris said, is that as you move south, the difference between high and low tide is greater. The larger volume of water moving past the southern islands toward the mainland opens more channels in the barrier islands, separating them. The tides also pile more sand on the back of barrier islands, widening them farther south. [Read: 7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

Up north, the difference between high and low tide is smaller and the waves are stronger. The waves tend to move sand parallel to shore, smearing long, narrow strips of sand along the coast.

Regenerating islands

Storms can inundate barrier islands, so they aren't such a safe place to be when a hurricane is approaching. Some storms even wipe barrier islands off the map. This disappearing act isn't necessarily permanent, however.

"In the Gulf Coast, some of the barrier islands off the Mississippi River get washed out during big storms but then will come back the next season or a couple seasons later," Romans said. "Just the very tops of them get chopped off, essentially."

The islands are able to "grow" back because the sand doesn't move far, often just offshore, Voulgaris said.

"When the hurricane passes, milder waves come to rebuild, using the same sand that has been shifted to different locations," Voulgaris said.

The problem comes when humans build beach homes and fishing piers on these dynamic environments, Voulgaris said. Humans are unwilling to wait for nature to rebuild what's been lost, and man-made structures may disrupt the redistribution of sand, meaning that when milder waves do come, they have nothing to rebuild with. For instance, the Chandeleur Islands in the Gulf of Mexico have not recovered the surface area they lost in Hurricane Katrina in 2005, LiveScience reported last year, because dams and other diversions along the Mississippi River are keeping island-building sediment out of the Gulf.

For the most part, though, it's not nature that suffers the most when a monster like Hurricane Irene is screaming toward shore.

"Hurricanes are very impressive. It's a lot of power. But the destruction is more in human-made structures," Voulgaris said. "Nature usually recovers."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.