Caribbean Pirate Life: Tobacco, Ale … and Fine Pottery

They smoked like the devil, drank straight from the bottle, annoyed the Spanish and had a fascination with fine pottery.

Oh, and they didn't use plates ... at least not ceramic ones.

Based in 18th-century Belize, they were real "Pirates of the Caribbean" and now new research by 21st-century archaeologists is telling us what their lives were like.

Their findings, detailed in a chapter in a recently published book, suggest that while these pipe-smoking men acted as stereotypical pirates would — drinking, smoking and stealing — they also kept fancy, impractical porcelain in their camps. The fine dinnerware may have been a way to imbue the appearance of upper-class society. [See photos of the pirate loot discovered]

Caribbean pirates

From historical records scientists had known that by 1720 these Caribbean pirates occupied a settlement called the "Barcadares," a name derived from the Spanish word for "landing place." Located 15 miles (24 kilometers) up the Belize River, in territory controlled by the Spanish, the site was used as an illegal logwood-cutting operation. The records indicate that a good portion of its occupants were pirates taking a pause from life at sea.

Their living conditions were rustic to say the least. There were no houses, and the men slept on raised platforms with a canvas over them to keep the mosquitoes out. They hunted and gathered a good deal of their food.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Capt. Nathaniel Uring, a merchant seaman who was shipwrecked and spent more than four months with the inhabitants, described them in the book The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring (reprinted in 1928 by Cassell and Company) as a "rude drunken crew, some which have been pirates, and most of them sailors."

Their "chief delight is in drinking; and when they broach a quarter cask or a hogshead of Bottle Ale or Cyder, keeping at it sometimes a week together, drinking till they fall asleep; and as soon as they awake at it again, without stirring off the place." Eventually Captain Uring returned to Jamaica and, in 1726, published an account of his adventures.

Pirate research

Over the past two decades a steady stream of archaeological research has increasingly shed light on the people who lived at the Barcadares.

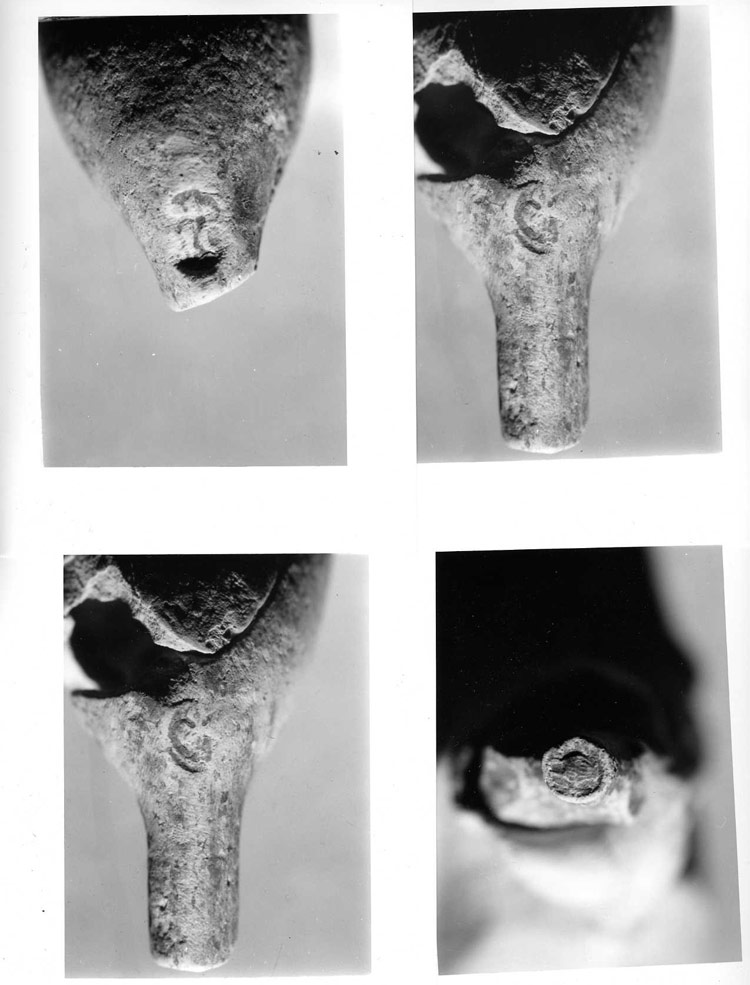

In the 1990s archaeologist Daniel Finamore, now a curator with the Peabody Essex Museum, led a team that rediscovered the Barcadares site. Its precise location had been lost since it was abandoned in the mid-18th century and the team found it with the help of a map drawn by Captain Uring.They excavated it, uncovering decorated pottery fragments known as delftware along with a small amount of authentic Chinese porcelain. They also found tobacco pipes, nails and ceramic bowls, among other items.

More recently, Heather Hatch, an archaeologist who is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University, performed an analysis comparing the artifacts found at the Barcadares site with that of two British colonial sites, sans pirates, on the island of Nevis.

"The Barcadares is the only clearly pirate-associated site from this period excavated to date," Hatch wrote in her report, recently published as a chapter in the book "The Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes"(Springer Science and Business Media, 2011).

"There are few pirate sites to examine, period. The few pirate shipwrecks that have been excavated are embroiled in debates over ethics and identification," she wrote. [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

Smoke like the devil

The differences between the Barcadares and the two non-pirate sites, also occupied during the 18th century, on Nevis are striking.

Both British sites were excavated by Marco Meniketti, who is now a professor at San Jose State University. The Ridge Complex site consisted of a sugar mill and related dwellings, while the Port St. George site, on the southern coast of the island, was used to process and transport sugar.

One stark difference between the sites was the sheer amount of tobacco use at the Barcadares. Pipes make up 36 percent of the artifacts found at the pirate site, compared with 22 percent at the Ridge Complex and 16 percent at Port St. George. Hatch told LiveScience that she is not aware of another site from this period with such a high proportion of tobacco pipes. "Percentage-wise, it's the highest that I know of."

The pirates, while at sea, would've had a lot of time on their hands, time they likely spent smoking heavily, Hatch said.

"They're not going to be sword fighting all the time," she said. "There's a lot of down time when you're a pirate, when you're sitting around in your ship, when you're waiting for prey, waiting for someone to attack or when you're sailing from point A to point B." [Read: Pirates Still Terrorize High Seas]

She also pointed out that "pirate activity wasn't regulated on a ship the same way it was on a merchant ship or navy," and that pirate crews were larger and "generally speaking that there was less work for everyone to do."

Peabody curator Finamore added that the mostly male makeup of the pirate site could explain the high level of tobacco pipes found, "where there are more males there is more smoking going on."

Fine pottery

In addition to finding smokes, Hatch's analysis revealed differences in ceramics found. The pottery on the two Nevis sites is made from diverse materials, including various types of tough, practical stoneware.

However, more than 65 percent of the pirate ceramics is made up of delftware — a soft, decorative material that was finished with a glaze. It is less sturdy than stoneware and not terribly practical for people living in a remote location.

"It's sort of soft pottery that has a glaze on it that can be quite pale," Hatch said. The pirate site also has a small amount of Chinese porcelain that was transported half way across the world.

Why the pirates would keep such impractical things in their camp is a mystery. Finamore pointed out that there were no legitimate trade routes in fine pottery that would have reached Belize at the time the pirates were living there.

"It seems most likely to me that they would have been part of booty," he said. The pirates likely either captured it themselves or traded with someone who did.

Finamore believes that the porcelain and delftware would have been prized possessions for the pirates. "They're sort of copying the appearances of upper class societies such as how the captains would live."

Hatch agrees, "I do think it was a matter of wanting to display that they could have these nice things," she said. It would have made a point that, even out in Belize, they had "access even to these sorts of fancy pottery types that you might find in the bigger cities in the colonial world."

Real pirates use bowls

While the pirates liked glittering pottery, they liked it mainly in two forms – bowls or porringers. The people who lived at the two Nevis sites, on the other hand, had a mix of plates, storage jars, saucers, tankards and mugs, among other objects.

It’s possible that some of the tableware was made of wood, and has since decomposed. Another possibility, the researchers suggest, is that the pirates simply didn’t feel a need for it.

"You can use a bowl for anything you can use a plate for pretty much. But you can't use a plate to eat, for example, cold soup," Hatch said.

Finamore believes that "the bowl form is more reflective of a communal eating activity." Unlike the people of Nevis, the pirates would have eaten more informally. "I somehow doubt that the Barcadares set tables; they probably ate communally out of the same bowls."

As for why no cups were found at the Barcadares site, Finamore and Hatch suggest that the pirates could have drank from wooden containers.

However, the explanation could be even simpler.

"I don't think they would have any qualms whatsoever about drinking straight from the bottle," Hatch said.

Finamore recalled that after he had found the Barcadares site, he shared the location with Emory King, a well-known Belize historian who has since died.

King told him that in the 1960s the bend in the river where the site is located was known as a great place for bottle diving. "People had gone out there, dived into the river, and pulled out very old bottles," Finamore said.

These bottles would not have been thrown away after a one-time use. "The nearest bottle manufactory, from the Barcadares site, was a long, long way away."

But despite the value of the bottles, and perhaps while under the influence of alcohol, the pirates would sometimes chuck them into the river.

"Some of them sometimes found their way into the river," Finamore said.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.