The Most Monumental Monument Mistakes

When you're a sculptor setting something in stone, you've only got one shot to get it right. Sometimes that isn't enough.

From factual flubs to grammar goofs, here's a handful of the biggest blunders ever emblazoned in boulders. [See the full gallery here]

The Drum Major

The Martin Luther King, Jr., National Memorial opened to much fanfare in August 2011. There was much excitement about an African-American non-President joining the precession of white Presidents decorating Washington D.C.'s mall, but objections followed soon after the monument was unveiled. Many commentators think the monument, and particularly the wording on it, makes the humble, gentle statesman appear "like an arrogant twit," as the African American writer Maya Angelou put it.

The larger-than-life MLK is standing highly-and-mightily, with his arms folded and his glare icy, critics point out. Worse still, a misleading misquote decks his stony flanks. The inscription reads: "I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness."

While it sounds boastful, the original quote that it paraphrased had quite the opposite tone. In a speech, MLK was addressing those who believed his civil actions to be self-serving or attention-seeking. He said, "Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter."

Many critics, including Angelou, believe the monument-makers ought to break out their chisels once more and expand the paraphrase, restoring its true intent. Nailed it

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Four Corners Monument marks the point where the states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico meet. For a century, tourists have ventured to the spot to straddle them all at once, striking poses straight out of a game of Twister for the best and goofiest Four Corners photos.

Trouble is, the monument is a bit off the mark. Congress designated the meeting point of the states at a longitude of 109 degrees 03 minutes West and a latitude of 37 degrees North. But Chandler Robbins, the surveyor hired to find this coordinate in 1875, picked a spot 1,800 feet too far east, and that's where the Four Corners Monument was plopped down. Still, as the National Geodetic Survey pointed out in a statement in 2009, considering the primitive technology then available to Robbins, "he 'nailed' the location."

Despite the error, the position of the monument officially established the boundary point between the four states at that spot. As the NGS put it, "In surveying, monuments rule!" Bronze Babe

In 1995, a bronze statue of Babe Ruth was unveiled in front of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the home field of the Baltimore Orioles, the team with which the Great Bambino began his professional career in 1914 (the Orioles were a minor league team at the time). In the statue, he's leaning on a bat and clutching a right-handed fielder's glove on his hip.

Unfortunately, the real Babe was a lefty.

Susan Luery, the artist who sculpted the statue, claimed to have gotten the mitt she used as a model for the sculpture from the Babe Ruth Museum. She believed it belonged to the Sultan of Swat himself, but in actuality, the museum's director had sent her a vintage glove similar to the one used by Ruth, but oppositely-handed. [Who Was the Greatest Baseball Player Ever?]

As the statue, called "Babe's Dream," grew from a model to a 9-foot-tall bronze monument, no one noticed the error. "They debated the belt loops, the hat, the hose he wore, and everything else. But no one said anything about the glove," Luery told the Baltimore Sun soon after the statues unveiling.

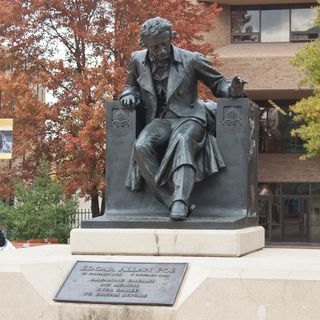

Po' Poe

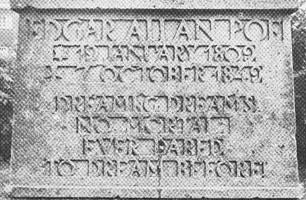

A bronze statue of Edgar Allan Poe stands near the University of Baltimore School of Law in Maryland. Sculpted by Moses Ezekiel in 1916 and erected in 1921, the monument's original base (later replaced) was inscribed with a line from Poe's most famous poem, "The Raven." It read:

"Dreamng dreams no mortals ever dared to dream before."

Yes, the "i" was omitted from the first word, but that didn't bother Poe enthusiasts nearly as much as the addition of "s" to the end of the fourth. Edmond Fontaine, a Baltimore resident and poet, took the typo personally. In 1930, after several years of regularly writing letters of complaint to local newspapers, he finally took a chisel to the statue to remove "the offending letter … for the good of my soul," he explained at the time.

Fontaine was initially arrested for chiseling off the "s" but was later released with a warning. When the statue was moved in the 1980s, the original base was replaced, and the typos corrected.

Memory man

The George Washington Monument in Mount Vernon, built from 1815 to 1829, listed the date of the president's inauguration as March 4, 1789. Washington was actually inaugurated on April 30; March 4 was the date Congress met in New York for the first time under the new Constitution. Incredibly, no one noticed the error until 1985. That year, longtime Mount Vernon resident Phil Easter, who described himself as "the amazing memory man," spotted the error immediately upon glancing at the monument's base. He informed officials, and the inscription was soon corrected.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.