Early Europeans Practiced Human Sacrifice

Europe's prehistoric hunter-gatherers may have practiced human sacrifice, a new study claims.

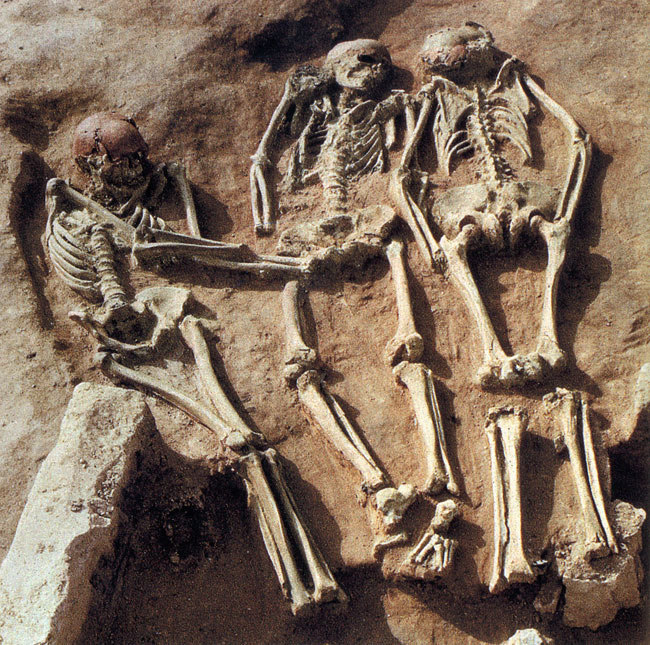

Investigating a collection of graves from the Upper Paleolithic (about 26,000 to 8,000 BC), archaeologists found several that contained pairs or even groups of people with rich burial offerings and decoration. Many of the remains were young or had deformities, such as dwarfism.

The diversity of the individuals buried together and the special treatment they received could be a sign of ritual killing, said Vincenzo Formicola of the University of Pisa, Italy.

"These findings point to the possibility that human sacrifices were part of the ritual activity of these populations," Formicola wrote in a recent edition of the journal Current Anthropology.

Multiple burials common with disease

Most of the hunter-gatherers who lived in Europe during the Upper Paleolithic buried their dead, and their graves—numerous and usually filled with offerings such as beads and ivory—are considered a good source of information on what they thought about spirituality and the afterlife, Formicola said.

Two or more people were occasionally buried together if they died in an accident or during times of disease, Formicola said. A cross-section of the graves reveal, however, that many of the multiple burials were more common than thought and had special circumstances surrounding the individuals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"All these multiple burials (one out of five) can hardly be the result of natural events … [and] human sacrifices could represent an additional explanation," Formicola told LiveScience.

Grave goods planned in advance?

For example, at a site in the Moravian region of the Czech Republic, three Paleolithic youngsters, one of whom was afflicted with congenital dysplasia, were discovered lying in unusual formation. The remains of an adolescent dwarf lying next to another female in Italy, as well as a pair of pre-teens in Russia treated to an elaborate grave offering of ivory beads, were also found.

"The time required to prepare all these ivory goods is enormous," Formicola said. "It was made for a ceremony and it was made specifically for the children. This leads [one] to wonder if this ceremony was foreseen long before the children's death."

The mix and match of ages and sexes buried in each grave indicates that they were put together for a reason and not just due to a common disease, said Formicola.

"These individuals may have been feared, hated or revered," said Formicola. "We do not know whether this adolescent received special burial treatment in spite of being a dwarf or precisely because he was a dwarf."

Aztecs tossed them from temples

Human sacrifices have never been apparent in the archaeological record of Upper Paleolithic Europe, though they pop up much later among more complex ancient societies, such as the Egyptians. The Maya and the Aztec would also cut out hearts or toss victims from the tops of temples, historians say.

The new findings could mean the hunter-gatherers were more advanced than once thought.

"What [the data are] suggesting is that the Upper Paleolithic societies developed a complexity of interactions and a common system of beliefs, of symbols and of rituals that are unknown in small groups of modern foragers," said Formicola.

- See the Mysterious 'Bog People'

- Medieval Torture's 10 Biggest Myths

- Evidence May Back Human Sacrifice Claims