History's 12 Most Doting Dads

Loving Fathers

History has its share of bad dads. Consider Russian czar Ivan the Terrible, who beat his pregnant daughter until she miscarried. When his son confronted him about it, Ivan struck the younger man's head with a staff, killing him.

But we're looking on the bright side. Here's a list of historical dads who did right by their kids. [The Animal Kingdom's Most Devoted Dads]

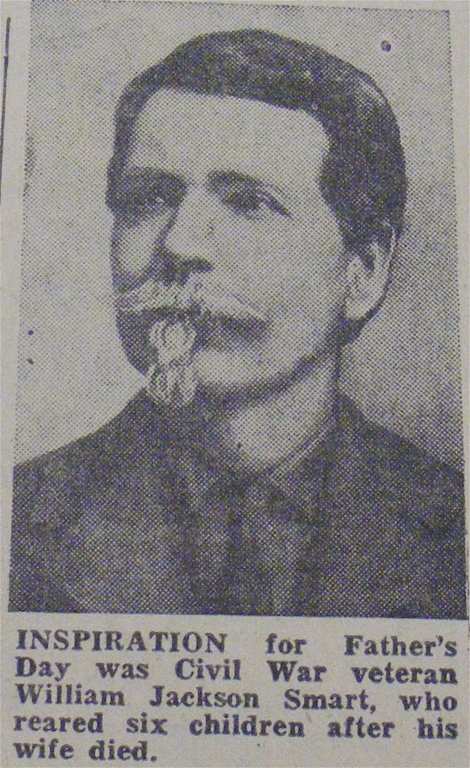

William Jackson Smart, 1842-1919

Smart was a Civil War veteran whose wife died during the birth of the couple's sixth child, leaving him to raise the children on his own in Spokane, Wash. In 1910, one of those children, Sonora Smart Dodd, would push for a new holiday celebrating her dad and others like him. Father's Day was set for the third Sunday in June, and the rest is history.

Charlemagne, A.D. 742-28

The first ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne is known as the "Father of Europe." He was also an actual father, and possibly a bit of a softie. One of his (possibly illegitimate) children was Pepin the Hunchback, so named because of a spinal deformity. Charlemagne treated his son well, favoring him over his younger brothers as was appropriate in royal lineages. But when he chose a younger (legitimate) son as his successor, Pepin the Hunchback became involved in a plot to kill Charlemagne, his wife and his legitimate children.

The plot was exposed, but even here, Charlemagne showed some fatherly mercy. Instead of executing his son along with the other conspirators, he banished Pepin to a monastery, where he lived out the rest of his days.

Charlemagne also doted on his daughters, keeping them close to the royal court and educating them. When they took up with courtiers and produced illegitimate grandbabies, he indulged those children, too. After Charlemagne's death, he bequeathed his surviving daughters convents where they could live out their days.

Li Yanwen, circa 1500

Hardly a household name, Li Yanwen was partially responsible for the blossoming of one of Chinese medicine's most famous practitioners, Li Shizhen. When his son was young, Li Yanwen urged him to take the civil services exams that would win him a position in the state bureaucracy. But Li Shizhen had other plans: He wanted to be a doctor like dear old dad.

Eventually, Li Yanwen gave in and mentored his boy, who by this time had proven himself utterly hopeless as passing the civil service exams. Li Shizhen would go on to become China's greatest naturalist and the author of "Bencao Gangmu," a sort of bible of Chinese medicine.

Thomas More, 1578-1535

A counselor to Henry VIII of England, More refused to support the King's split from the Catholic Church. For his trouble, he was arrested for treason and beheaded. [Read Execution Science: What's the Best Way to Kill a Person?]

But before all that, More was a good dad. He provided his three daughters the same classical education as his son, which was very unusual for 16th-century England. During More's imprisonment for treason in the Tower of London, his oldest daughter Margaret Roper visited him frequently. After his death, Roper bribed the man who was supposed to throw her father's head into the Thames River, saving it for a decent burial instead.

Vespasian, A.D. 9-79

Successful military man Titus Flavius Vespasianus Augustus (or Vespasian for short) ascended the throne of Rome in A.D. 70. The emperor had three children, including two sons, Titus and Domitian. He and Titus had long worked together on the battlefield, and now one of Vespasian's major goals was to be sure his sons could rule after him.

Witty and amiable, Vespasian's last words as he died in 79 were reportedly, "Oh! I must be turning into a god," a quip referencing the deification of dead Roman emperors. God or not, Vespasian secured Rome for his sons. Titus ruled for two successful years until his death in 81. But Domitian, the less-favored son, got crossways with court officials during his rule and was assassinated in 96.

Lieutenant-Colonel George Lucas, circa 1700

Lucas' greatest attribute as a father was his ability to recognize greatness and stay out of the way. His daughter Eliza Lucas (later Eliza Lucas Pinckney) showed talent from a young age. Instead of consigning her to the type of half-hearted schooling that upper-class British girls got at the time, Lucas secured Eliza a real education. She later wrote to him that it was "a more valuable fortune than any you could have given me."

When Eliza was 14, the family moved from her birthplace in Antigua to South Carolina, but Lucas had to return to the island a year later. By the time Eliza was 16, she was running the family's three plantations in South Carolina. Lucas would send her various seeds from Antigua, which she would test in South Carolina. One of these seeds was indigo. Eliza made it work, launching a crop that would become second only to rice in the amount of money it brought to South Carolina.

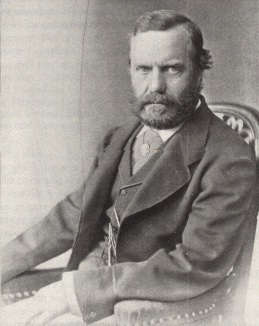

Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., 1821-1878

U.S. president Roosevelt Jr. called his father "the best man I ever knew." In fact, Teddy's tribute to his father in his autobiography is so moving that we'll let him explain what made his old man great:

"He combined strength and courage with gentleness, tenderness and great unselfishness. He would not tolerate in us children selfishness or cruelty, idleness, cowardic, or untruthfulness. As we grew older he made us understand that the same standard of clean living was demanded for the boys as for the girls; that what was wrong in a woman could not be right in a man. With great love and patience, and the most understanding sympathy and consideration, he combined insistence on discipline …

"My father worked hard at his business, for he died when he was forty-six, too early to have retired. He was interested in every social reform movement, and he did an immense amount of practical charitable work himself. He was a big, powerful man, with a leonine face, and his heart filled with gentleness for those who needed help or protection, and with the possibility of much wrath against a bully or an oppressor."

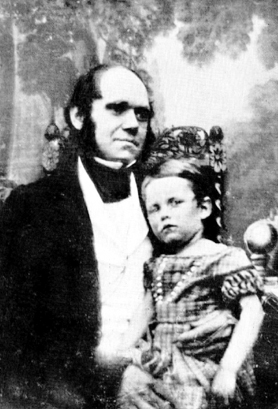

Charles Darwin, 1809-1882

The naturalist and father of evolutionary theory had 10 children with his wife, Emma Wedgwood. He doted on his children, and was devastated by the death of 10-year-old daughter Annie in 1851. His other children remembered him as a loving storyteller who took interest in their lives and encouraged their freedom.

"Indeed, it is impossible adequately to describe how delightful a relation his was to his family, whether as children or in their later life," Darwin's daughter Francis wrote in "Autobiography of Charles Darwin and Selected Letters" (Dover Publications, 1992).

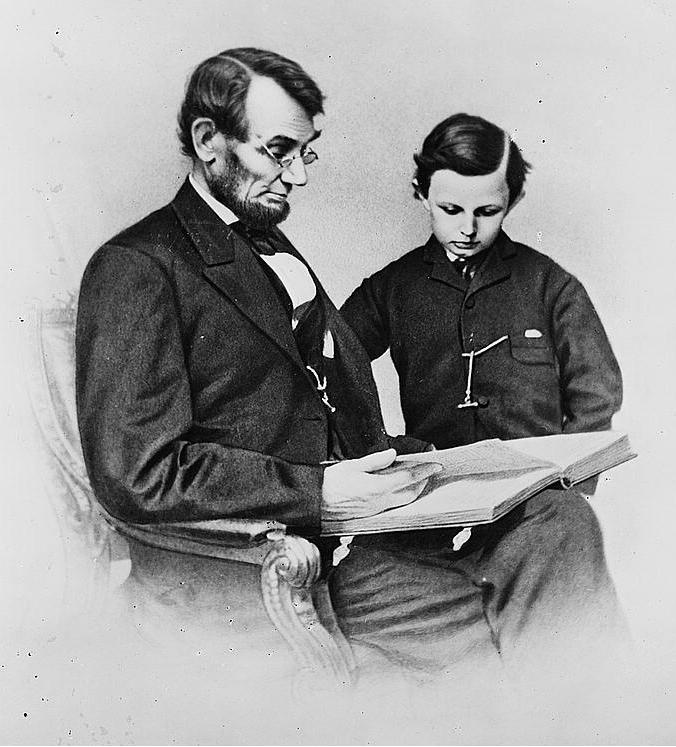

Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1865

When Abe Lincoln was president, the White House pitter-pattered with the sound of children's feet. Lincoln adored his children and reportedly gave them free reign to run, play and even interrupt Cabinet meetings.

The Lincolns had four children, but only one, Robert Todd Lincoln, would live to adulthood. The deaths of their children left the Lincolns reeling. When 11-year-old Willie died in 1862, Lincoln wrote, "I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!"

Nicholas II, 1861-1918

Speaking of family tragedies, Nicholas II of Russia would eventually be murdered along with his wife and children by Bolsheviks. But during his life, Nicholas II seems to have been a concerned father, albeit a poor ruler.

Nicholas and his wife Alexandra had four daughters and a son, Alexei. Unfortunately, Alexei had hemophilia, a blood disorder that left him susceptible to uncontrolled bleeding. Nicholas worried about his heir, said Brian Pavlac, a professor of history at King's College in Pennsylvania. But he let his wife call in the infamous faith healer Grigori Rasputin, which his political enemies later used against him as the healer gained influence in the court.

By the way, Rasputin himself had a daughter, who wrote several memoirs defending her father's honor. Maria Rasputin escaped Russia a few years after her father's death and became a cabaret dancer, a governess, a cookbook author and a lion tamer. (Really.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.