Ancient Eggs and Tiny Teeth Reveal Oldest Shark Nursery

More than 200 million years ago, a now-rocky section of southwestern Kyrgyzstan was a freshwater lake, ringed with horsetails and conifers — and full of baby sharks.

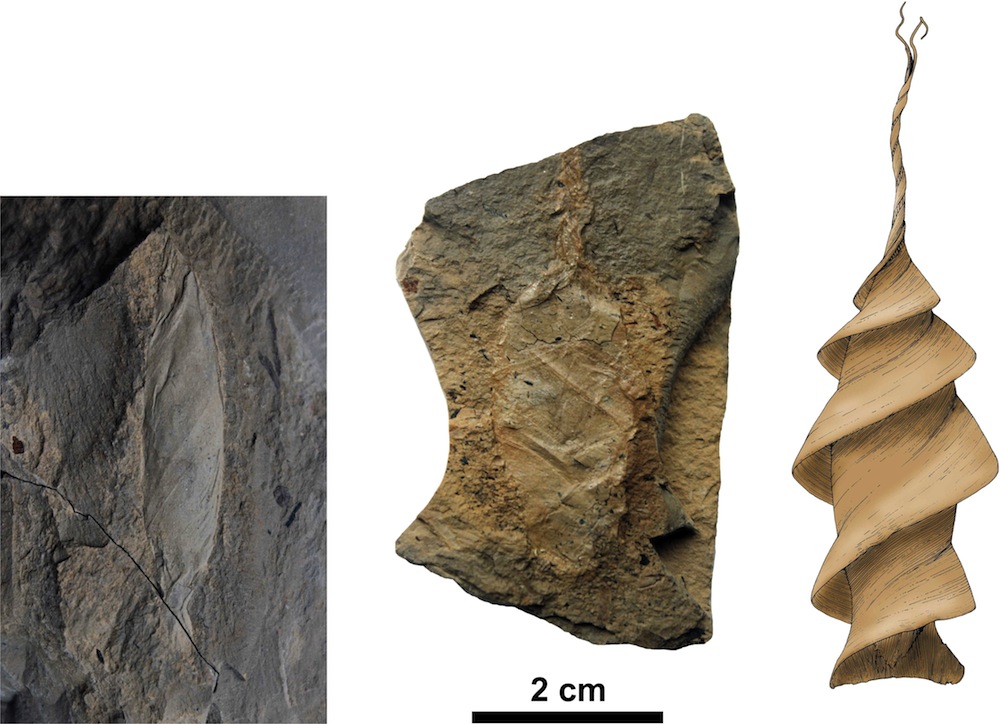

Those are the findings of a painstaking paleontological search that turned up tiny shark teeth just a millimeter long, along with rare imprints of coiled and twisted shark egg cases. The fossils mark the lake bed as a former shark nursery, the oldest where egg cases and teeth have been found together.

"Nurseries are known, especially for modern sharks," study researcher Jan Fischer, a paleontologist at the Geologisches Institut, TU Bergakademie Freiberg in Germany, told LiveScience. "This is the first study that proves the existence of this pattern in the Mesozoic."

Small freshwater sharks aren't the only ancient sharks that hatched in nurseries. In 2010, researchers reported in the journal PLoS ONE that they'd found a trove of baby megalodon teeth suggestive of a nursery. These saltwater sharks, which lived between 17 million and 2 million years ago, could grow to more than 52 feet (16 meters) long.

Baby shark teeth

The Mesozoic era stretched from 250 million years ago to about 65 million years ago, coinciding with the time when dinosaurs walked on the Earth. Unlike today's sharks, some species of Mesozoic sharks lived in freshwater. [On the Brink: A Gallery of Wild Sharks]

"You could be freshwater fishing and pull out a foot-long shark," said Andrew Heckert, a paleontologist at Appalachian State University who was not involved in the current study. Judging by fossil shark teeth, Heckert told LiveScience, these freshwater species likely grew to no more than 3 feet (1 meter) long. They likely ate small-shelled creatures similar to modern crayfish and clams.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They probably weren't terrifying predators unless you were a small invertebrate," Heckert said.

The new find, reported Thursday (Sept. 8) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, consists of dozens of tiny teeth as well as fossilized fragments from the egg capsules of two different species of shark. To uncover these fragments, the scientists sifted through pounds of material as part of a larger project that seeks to outline the ancient ecosystem of the now-vanished lake. Teeth are usually the only fossilized remains of sharks, because the animals' cartilage skeletons do not fossilize well. To isolate shark baby teeth, researchers must dissolve away large amounts of rock, leaving the tiny fossilized triangles behind.

The researchers were able to identify the owners of one type of egg case and teeth as hybodontids, a family of sharks that died out 65 million years ago with the dinosaurs. The other sharks that left behind egg cases were likely xenacanthids, which died out at the end of the Triassic period, 250 million years ago. The specimens were about 240 million years old. [See Images of the Fossils]

A nursery for sharks

The presence of small teeth and egg capsules, but no sign of adult sharks, suggests the shallows of the lake served as a shark hatching ground at this time, Fischer said. By analyzing the chemical makeup of the teeth, he and his colleagues confirmed that the baby sharks did indeed hatch in freshwater.

That means that ancient sharks were both similar and remarkably different than their distant relatives today. They carried out similar breeding behaviors as modern sharks, which are known to establish nurseries in shallow, protected waters. But they also survived in freshwater, an unknown feat for sharks today.

It's not known where these particular adult sharks went after they left their eggs in the nursery area. They probably lived their lives in deeper waters in the lake, Fischer said, though they also could have been ocean-dwellers who swam upstream to spawn, much as salmon do today.

"We can just speculate," Fischer said. "We think they are from the freshwater itself, but we have no proof."

The find will change the way scientists look for evidence of ancient sharks, Heckert said. Very often, impression fossils like those of the egg cases aren't well preserved in the same spots that keep fossilized bones and teeth safe, he said.

"We need to try to figure out where we need to be looking to see this stuff in the future," he said. "This will affect the way we do paleontology and what we look for in other places, because these fossils are found all around the world."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.