Bones of Roman-Era Babies Killed at Birth Reveal a Mystery

The bones spent close to a century in 35 small boxes meant to hold loose cigarettes and shotgun cartridges, each box big enough to hold the complete skeleton of one infant. Then Jill Eyers found them in a museum archive.

"It was quite heart-rending, really, to open all these little cigarette boxes and find babies inside," said Eyers, an archaeologist and director of Chiltern Archaeology in England. "But they kept very well over 100 years."

These remains were already ancient by the time they were excavated from the English countryside in 1912 and put into boxes. Eyers estimates they are now about 1,800 years old, dating back to the time when England was part of the Roman Empire.

These 35 babies appear to have died soon after they were born, the victims of infanticide. But while these deaths clearly seem unnatural, Eyers and a fellow researcher disagree on the circumstances behind them, with Eyers suspecting a brothel was to blame. [Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal With the Dead]

Discovered, the first time

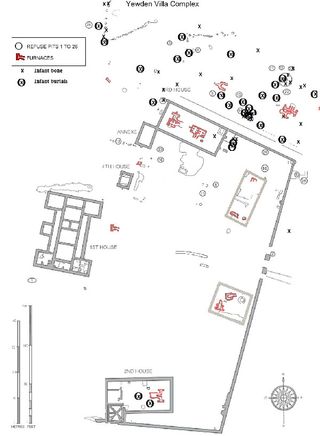

Responsible for tucking these bones away in small boxes is curator of the Buckinghamshire County Museum, Alfred Heneage Cocks. In 1912, Cocks led an excavation at the former site of a Roman villa in the village of Hambleden. He reported uncovering 103 burials, 97 of them infants, three children and three adults, mostly in an area near the north end of the villa. But the materials Eyers' found indicate there may be some error in these tallies.

In a report published nine years later, Cocks described the skulls of the adults, whose bodies appear to have been thrown down a well, along with the building plans of the villa, and a report on pottery and other items found. He mentioned the infants only in passing.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the remains that turned up in the boxes, Eyers and colleague Simon Mays studied the 35 most complete and intact skeletons. Many of the excavated burials remain unaccounted for, but Eyers believes they may still be found.

As for why Cocks didn't examine the infant skulls, Mays said, "There was no real research interest in infant skeletons at the time."

Rather, in the early 20th century in Britain, archaeologists focused on trying to reconstruct the history of the British people, which they saw in terms of waves of invaders and identified through the shape of adult skulls, according to Mays, who is a human skeletal biologist with English Heritage, a governmental advisory organization. (The skull-shape approach is no longer used.)

Eyers suspects another explanation for the lack of investigation by Cocks: "I don't think he could deal with the idea that these babies had been killed," she said. [Fight, Fight, Fight: The History of Human Aggression]

Cocks wrote that the infant skeletons were found to the north of the site, and speculated that they had been buried secretly after dark, a conclusion he reached because one baby's burial cut into another, according to Eyers.

At some point, the recovered remains disappeared, and interest in them grew over time. Eyers was reading through Cocks' letters when she found a scribbled note saying he had placed their remains in boxes marked "various." She later found the boxes in Buckinghamshire County Museum's archive, where they had arrived after the museum holding them, in Hambleden, closed in the 1960s.

Eyers then called in Mays, who has studied the infanticides of Roman Britain, to take a look at the bones.

Why?

Before and around birth, a child's bones grow rapidly, so by examining the length of long bones, including upper arm and thigh bones, it is possible to place the time of death to within about two weeks. When Mays examined the remains of the 35 infants, he found that many seemed to have reached about 38 to 40 weeks gestation, the age at which most babies are born.

"The reason we think the pattern is indicative of infanticide is: If they were natural deaths, you would expect a few to die a bit prematurely, some to die at birth, some to die in the days and weeks after birth," he said.

In fact, the spike in deaths right around the time of birth matches the profile of infant remains found in a sewer in Ashkelon, a site in Roman-occupied Israel believed to hold a brothel. By comparison, the babies buried in a medieval English cemetery, in the Wharram Percy churchyard, show a wider distribution of ages, with no peak at around the age of birth, indicating natural deaths.

Eyers believes the Hambleden site, now covered by a farmer's field, may echo the brothel, where, in the absence of reliable birth control, prostitutes bore and exposed unwanted babies. She estimates that a third of the 35 had been buried between A.D. 150 and 200.

"Why were they doing this at this site? It doesn't make sense," Eyers said. "This site was exceptionally wealthy — they could have kept babies — so it wasn't because of the poverty. There were no natural illnesses that would affect just the little ones, the newborns. There is no logical reason we can think of, except maybe it was a brothel."

Although the villa, which would have resembled a big country house, appeared isolated, there is evidence of passing traffic, which could mean customers for a brothel, Eyers argues. She points out the nearby Thames River becomes too shallow during the summer for ships to pass, making it likely that passengers disembarked here. She also found evidence of an ancient path leading from the vicinity of the villa to the market town of Dorchester and said a pot with an erotic design was found at the site.

Mays, however, disagrees.

"I think it was a routine way parents could make choices about family size," he said of infanticide. "You don't need a special explanation; it was part of a widespread phenomenon."

These infants could have been the children of the villa owners or their laborers, he said. He has found evidence of infanticide at a variety of sites from Roman-era Britain.

Until recently, societies around the world tolerated infanticide because, prior to modern methods of contraception, it was one of the few ways of limiting family size that was both effective and safe for the mother, he and Eyers wrote in an article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

In Roman times, "we know newborn babies weren't viewed in the same light as older babies and children as they were growing up," Mays said.

In order to achieve a fully human status, babies needed to survive to about 6 months old, Mays said.

"We have in our minds a criteria for becoming human, and in the Roman world it was just later," he said.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.