Belief in 'Da Vinci Code' Conspiracy May Ease Fear of Death

A love of Dan Brown and his hit book "The Da Vinci Code" may be a coping mechanism in the face of death — at least if you believe what you read.

A new study finds that people who are anxious about death are more likely to believe in the conspiracy theories outlined in Brown's book (Doubleday, 2003). The thriller follows a cryptographer and a symbologist as they unravel a mystery about the secret of the Holy Grail.

"It's difficult to change people's beliefs in these theories because they tend to be very fundamental to the way they view the world," study researcher Anna Newheiser, a doctoral student in social psychology at Yale University, told LiveScience.

Conspiracy theories ahead

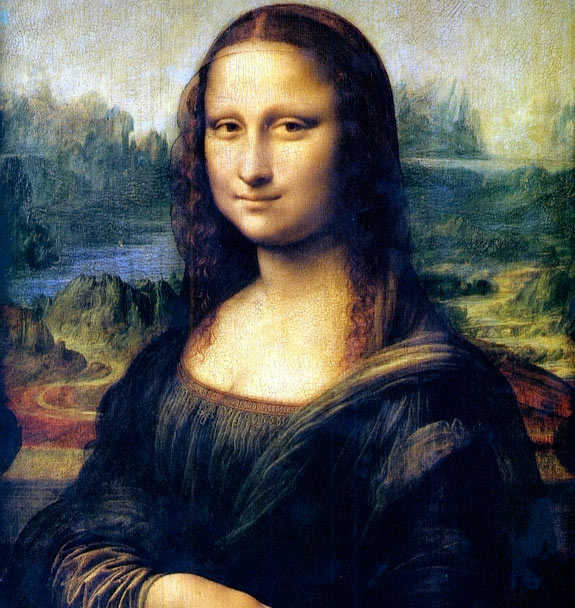

When "The Da Vinci Code" novel and a subsequent movie were released, Brown said in multiple media interviews that the historical background of the book, which included secret societies and massive cover-ups by the Catholic Church, was based in fact. Spoiler alert: The conspiracy in the book is that Jesus married Mary Magdalene and had children, leaving living descendents behind. The Catholic Church covered up this fact, according to the novel, while a secret society called The Priory of Sion works to keep Jesus' descendents safe.

Newheiser and her colleagues decided to use belief in this "Da Vinci conspiracy" to find out what people get out of believing in conspiracy theories. "The Da Vinci Code" was a good starting point, Newheiser said, because unlike other conspiracy believers, Da Vinci conspiracy believers are not marginalized as tin-foil hat types. [Read: Top 10 Conspiracy Theories]

The researchers gathered college students who had read the book and conducted two studies. In the first, they asked 144 students to rate their agreement with Da Vinci conspiracy beliefs, such as "The church has burned witches and other 'heretics' to keep the truth about Jesus hidden." The students also filled out questionnaires about their religiosity, biblical knowledge, enjoyment of "The Da Vinci Code" novel or movie, and their fear of death. They also answered questions about New Age beliefs, such as "The whole cosmos is an unbroken living whole that modern man has lost contact with."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Believing Dan Brown

The students most likely to believe the conspiracies in Brown's novel were those who enjoyed the book the most, expressed the most New Age beliefs, and felt the most anxiety about dying. People who were religious, knowledgeable about the Bible and desiring of social approval, on the other hand, tended not to buy into the Da Vinci conspiracy.

Next, the researchers called 50 of the original students back and presented them with historical evidence that the Da Vinci conspiracy is false. They found that among the most religious participants, this counterevidence lessened the belief in the conspiracy. Nonreligious participants, however, did not budge.

The study, published online Sept. 7 in the journal Personality and Individual Differences, is preliminary, Newheiser said. But the finding that people with death anxiety are more likely to believe in the Da Vinci conspiracy jibes with the theory that conspiracies, as wacky as they can be, provide a sense of comfort to adherents.

Conspiracy theories "can alleviate people's sense of loss of control by giving them a reason that things happen," Newheiser said. "In this case, it's particularly interesting because it might help people who are nonreligious or non-Christian to understand the events related to early Christian history."

Religious people have their own understanding of those events, Newheiser said, which may be why they were more easily persuaded that the Da Vinci conspiracy was false.

A similar need for control may be at play in other conspiracy theories as well, including the idea that the U.S. government had something to do with the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Newheiser said. She and her colleagues are launching more studies to examine a wider variety of conspiratorial beliefs.

"There is something very fundamental about the nature of these kinds of beliefs," Newheiser said. "There is past research showing that conspiracy beliefs don't really respond to counterevidence very well, because they're not based on logical arguments to begin with. Showing logical arguments against them doesn't change people's minds."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.