Irene's Impact on Bahamas Analyzed from Air & Sea

After Hurricane Irene blew through the Bahamas, scientists raced to the islands on helicopters and ships to inspect the aftermath and learn more about how cyclones affect coastal areas.

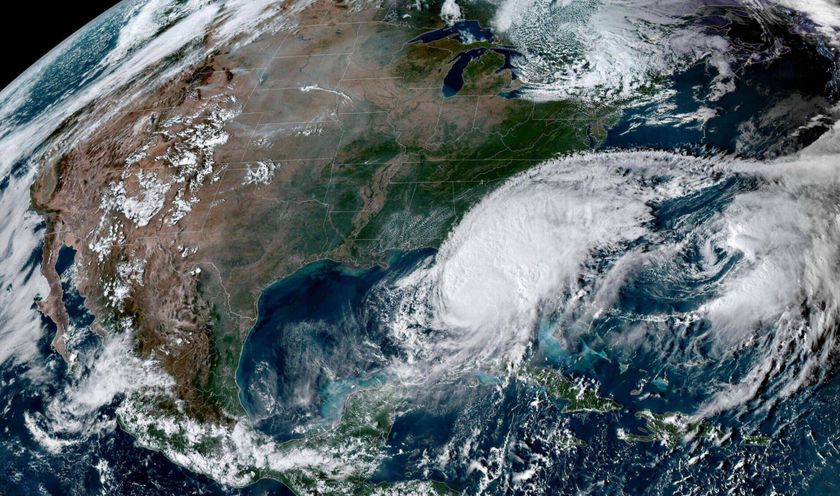

On Aug. 25, the center of Hurricane Irene passed over the Exuma Sound and the Exuma Cays in the Bahamas. The tropical cyclone was a Category 3 storm at the time, with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 kph).

Coincidentally, the University of Miami operates a field station in the Exumas. The location is interesting to scientists because the Exuma Cays have the only known examples of living stromatolites growing in the open sea.

"Stromatolites are reefs with a layered internal structure that were built by microbes rather than coral — they are Earth's first macro-fossils and dominated the Earth for 80 percent of the geologic record," said marine geologist Kelly Jackson at the University of Miami. "Photosynthesis by cyanobacteria forming these early microbial reefs generated the oxygen that allowed higher organisms — eventually including humans — to evolve."

In addition to studying stromatolites, researchers at the University of Miami are working in the Exumas to understand how changes in sea level over the past 500,000 years formed the islands and sculpted the coastal landscapes. To do so, they are mapping islands and shallow-water environments in conjunction with drilling into and extracting segments of rock to depths of 72 feet (22 meters) below present-day sea level. These cores act as a window into climates that existed in the past when the rocks were exposed at the surface.

All this expertise already in place in the Exumas gave researchers a unique chance to better analyze how hurricanes can affect coastal landscapes. Such knowledge "helps us understand possible effects from future storms so that coastal communities can better prepare before the storm comes," Jackson said. [Storm Targets: Where the Hurricanes Hit]

Also, this data helps scientists better understand the geological record and thus ancient history of the area, she added, since hurricanes would have had an impact on the islands long before humans began studying them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Flying in after the storm

Just days following the storm, Jackson, along with marine biologist Kasey Cantwell and climatologist Roni Avissar, boarded a helicopter in Miami to inspect the geological impact of Hurricane Irene from the Exumas to the outer bands of the storm on Andros, Joulters Cays and Cat Cay. The objective was to take images of the affected areas to better understand the storm's impact on different types of terrain. The helicopter crew used three camera setups — one digital single-lens reflex (SLR) camera mounted on a gyroscope set up to automatically take two pictures every two seconds, two digital SLRs with a wide angle and telephoto lens to concentrate on specific details, and a high-definition camera for video.

"This was the first time I have flown in a helicopter for research in the Bahamas and it was amazing," Jackson said. "The helicopter has a lot of windows and while we were taking photos, the back door was removed to accommodate the camera mount system. We had breathtaking views of the beautiful Bahamian islands and shallow water environments."

They captured more than 23,000 aerial photographs of the islands, coastlines and shallow water environments in just nine hours, documenting the immediate changes from the storm, mostly from an altitude of 1,000 feet (305 meters). The helicopter ride "allowed us to assess the damage to a large area in a matter of hours — ground-based surveys of the Exuma Cays alone would have taken a minimum of a couple weeks to complete," Jackson said.

At about the same time, marine geologist Gregor Eberli at the University of Miami and a group of Brazilian scientists onboard the research vessel Coral Reef II recorded the effects of the storm from Bimini to Nassau. In addition to taking pictures of the hurricane's effects, they collected samples of sediment and seawater in Irene's wake.

"It was essential to do a survey as quickly as possible to understand changes caused by the storm and create a benchmark so we can also observe how long it will take the coastal system to return to normal," Eberli said. "We know from working in the Bahamas that the daily tidal fluctuations will eventually minimize the effects of the storm."

All in all, "while there have been previous geologic studies that have studied the effects of hurricanes on the coastal environments, this was the first assessment conducted so quickly after a storm over such a large area," Jackson said.

Irene's effects

Along the center path of the storm in the Exumas, the hurricane caused significant beach erosion. The storm surge also damaged vegetation, and in a few shallow-water environments along the 105-mile–long (170 kilometers), 3-to-6-mile–wide (5 to 10 km) island chain, the waters were cloudy with sediment. [Nature to the Rescue: Barriers to Storm Surge]

"It was sad to see the damage to homes, buildings, boats and docks, and we hope that the Bahamas can recover quickly from Hurricane Irene," Jackson said.

Despite this damage, there were no major changes to the coastal landscape overall. For example, major channels remain unchanged and are still accessible by boat.

"Many geoscientists think that hurricanes cause major changes to submarine environments — this and some previous studies show that this is actually not the case," Jackson said.

Away from the storm's center but within the area of storm-force winds, the Andros coastline and offshore reefs experienced very minimal damage. There were a few broken corals but overall no major damage to the ecosystem, the researchers noted.

"These effects will recover within months to a couple years," Jackson said. "There will not be any long-term negative effects to the coastal landscape."

The large sub-tidal shoals of Joulters Cay and Cat Cay remained unchanged, while at Joulters Cay, the storm surge formed a new beach ridge 4 feet (1.2 m) higher than the normal beach level. The storm surge flooded Andros Island and deposited a millimeter-thick layer of fine white mud on the mangroves and tidal flats, while the waters on the leeward side of Andros were milk-white even six days after the storm.

Understanding the impact

Cantwell and the Coral Reef Imaging Laboratory at the University of Miami are now processing the 23,000 aerial photographs and creating giant mosaics from them. These images will then be integrated with mapping software and previous satellite and aerial photograph data "so that we can truly understand the geologic impact of a Category 3 tropical cyclone on the islands and coastal system," Eberli said.

Such a combination of aerial photography, satellite imagery and mapping software "can be applied to storms, tsunamis, rising sea level, and essentially any situation where large-scale coastal monitoring is needed," Jackson said. "This is a major step forward for coastal scientists — in the past, these types of studies were limited because you did not have the ability to rapidly assess a large area, and therefore results were based mostly on particular sites but not a regional area. This will be the future of coastal studies."

And the team isn't done investigating Irene's impact yet.

"We will continue to work in this area for many years to come," Jackson added. "We will be able to see exactly how long it takes for the system to fully recover moving forward."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.