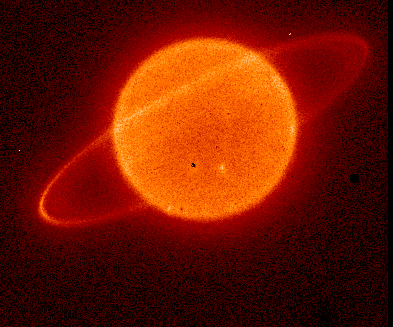

The distant "ice giant" planets Uranus and Neptune look like worlds aflame in new photos captured by Hawaii's Keck Observatory.

To the naked eye, Neptune would appear blue and Uranus bluish-green. But Caltech astronomer Mike Brown snapped the new pictures in infrared light, using Keck's adaptive optics system. So the two planets blaze reddish-orange, like embers glowing in the dark night of deep space.

Brown posted the pictures via Twitter from Sept. 18 to Sept. 20. Two shots show bright streaks on Neptune, which is about 17 times as massive as Earth and orbits 30 times farther from the sun than our planet does. [See the stunning photos of Neptune and Uranus]

These streaks represent high-altitude clouds that are reflecting a lot of light. Neptune is a stormy place, hosting some of the most violent maelstroms in the solar system.

Neptune and Triton

One image captures Neptune along with its largest moon, Triton, which is about 80 percent as big as Earth's moon.

Triton's composition is similar to that of objects in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy, rocky bodies beyond Neptune's orbit. As a result, many astronomers believe that Triton is a former Kuiper Belt object that the planet's gravity captured long ago. [Photos of Neptune, the Mysterious Blue Planet]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brown studies objects in the frigid outer reaches of the solar system, both in the Kuiper Belt and beyond. He has discovered a number of dwarf planets way out there, including the Pluto-size Eris in 2005 — a find that spurred astronomers to rethink just what a planet is (and, ultimately, to demote Pluto to "dwarf planet" status in 2006).

During the recent Keck observing session, Brown and his team were more interested in Triton than Neptune.

"We were studying Triton at the time, trying to see if we could make a crude map of its surface composition," Brown told SPACE.com in an email. "But Neptune is a little too spectacular to not stop and take a picture of it as long as you're nearby."

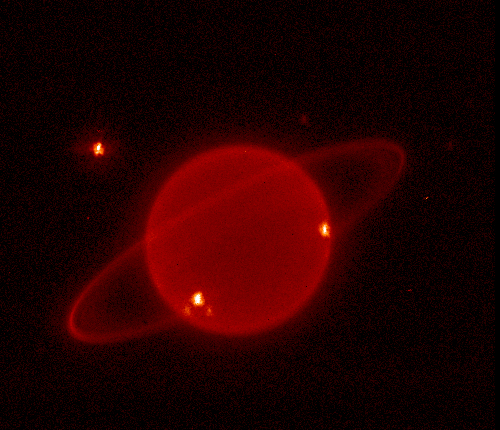

The rings of Uranus

Other photos show Uranus — which is 14.5 times as massive as Earth and orbits 19 times farther away than Earth does — in a whole new light. In particular, the pictures highlight Uranus' rings, which were discovered only in 1977. [Photos of Uranus, the Strange Tilted World]

"The rings are faint and really tough to see and not even discovered until moderately recently, but Uranus is so dark at these wavelengths that the rings are quite easy to see," Brown said.

One Uranus image shows several of the planet's 27 known moons, including one known as Miranda, which blazes bright above and to the left of Uranus. Despite being just one-seventh as big as Earth's moon, Miranda boasts canyons 12 times deeper than the Grand Canyon, as well as numerous other interesting geological features.

Again, the moon drew Brown's attention more than the planet.

"Here we were looking at Miranda, which is quite close to Uranus," Brown said. "But, again, we couldn't resist the photo opportunity."

Also visible in the photo is another, fainter moon, Puck, to Uranus' upper right. The bright spots on the planet's disk are high clouds, Brown said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.