Earth's Annual Resources Used Up Today, Group Says

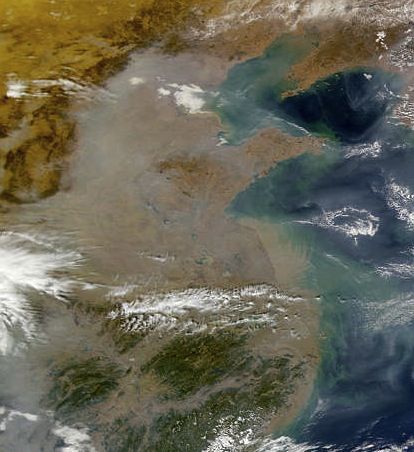

It's only September, but humans have used up the Earth's natural resources for the year, according to a sustainability nonprofit group.

The Global Footprint Network (GFN) has declared today (Sept. 27) "Earth Overshoot Day." That's the day when humankind's demand on nature exceeds the planet's ability to regenerate resources and absorb the waste.

"Our research shows that in approximately nine months, we have demanded a level of services from nature equivalent to what the planet can provide for all of 2012," according to a GFN statement. "We maintain this deficit by depleting stocks of things like fish and trees, and by accumulating waste such as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the ocean." [Read: Top 10 Alternative Energy Bets]

Running an ecological debt

Earth Overshoot Day is a rough estimate, but other conservation groups raise similar alarms about consumption of resources on planet Earth. The world's 7 billionth person is likely to be born next month, according to estimates by the United Nations. Meanwhile, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) estimates that humans currently consume the equivalent of 1.5 planets' worth of resources to maintain our activities.

"If current trends continue, by 2030 we will need the capacity of two planets to meet natural resource consumption needs and absorb CO2 [carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas] waste," according to the WWF's Living Planet Report.

According to the GFN, humans have been outliving our means since the mid-1970s, demanding more than the planet can renewably produce. (This is called "ecological overshoot.") In 2011, the GFN estimated that humans will use 135 percent of the resources the Earth can actually generate in one year. [Infographic: Human Demands Tax Earth's Resources]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results of overshooting

The result of this ecological overshoot, according to the GFN, is similar to being in debt in a household: The bills pile up. Climate change, for example, occurs because excess greenhouse gases get trapped in the atmosphere. Forests shrink because the trees can't grow back faster than humans cut them down. Overfishing causes fisheries to collapse. The WWF estimates that global biodiversity is down 30 percent since 1970.

"The environmental crises we are experiencing are all symptoms of an overall trend — humanity is simply using more than the planet can provide," the GFN wrote.

Last year's Earth Overshoot Day was a few weeks earlier than this year's, but that's due to revised calculation methods rather than to any environmental gains on the part of humanity, according to the GFN. The organization calculates Overshoot Day by estimating the world's biocapacity — including factors like the regrowth of forests and regeneration of fisheries — and comparing it with humanity's ecological footprint, the amount of land and sea it takes to produce everything we consume and dispose of all the waste. The concept of Earth Overshoot Day was originally devised by the U.K.-based New Economics Foundation.

Exact trends are difficult to calculate, but the GFN's best calculations suggest that the real Earth Overshoot Day has been moving three days earlier each year since 2001.

No matter how you do the calculations, the group finds the trends worrying.

"We are in significant overshoot, and overshoot is growing," the GFN said. "By any analysis, we are well over budget."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.