Astronomers Debate Where 1st Interstellar Starship Should Visit

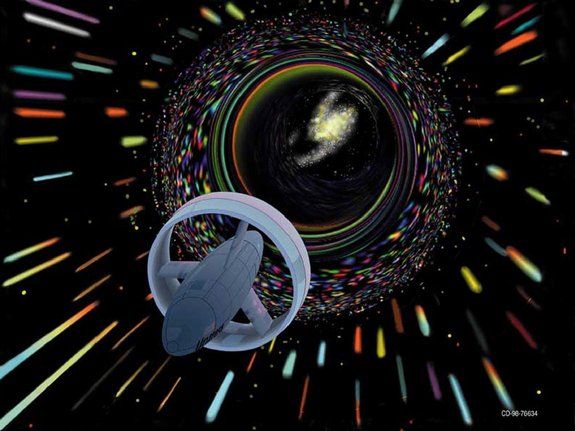

ORLANDO, Fla. — If humans ever build an interstellar spaceship —a vehicle capable of reaching another star — one of the biggest questions will be which of the billions of stars in the Milky Way should it visit?

Scientists debated possible interstellar destinations at the 100-Year Starship Symposium, a weekend meeting here sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to discuss planning the first mission to another star system.

Among the top priorities for choosing a star to target is its potential to harbor life, said astrobiologist Jill Tarter of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute. [Gallery: Visions of Future Human Spaceflight]

"It's really the story of life in the cosmos that is likely to drive exploration beyond the solar system," Tarter said."I think this is the question that will be worth the effort and the pain and the investment of traveling to another star system."

Tarter and other experts agreed that any interstellar mission should try to visit a star that has planets — hopefully planets the right size and distance from their stars to host life.

The symposium is part of the 100 Year Starship Study, a $1 million, one-year project of DARPA and NASA to look into what it would take to launch a mission to another star within a century. In November, the agencies plan to award $500,000 in seed money to an organization that can spearhead the effort to research the necessary technology and logistics.

Narrowing down the options

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Having planets isn't the only qualification the chosen star must meet. Another important criterion is its distance from Earth — the closer, the better.

At 4.4 light-years away from the sun, Alpha Centauri is our nearest stellar neighbor, putting it at the top of the list of candidates. However, even Alpha Centauri would be a long trip.One light-year, the distance light crosses in a single year, is about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

To put such a distance in perspective, one speaker at the symposium suggested an analogy: If the Earth was here in Orlando, and Alpha Centauri was in Los Angeles, then the entire solar system would span only 1 mile (1.6 km).

The farthest any manmade object has ever traveled is approximately to the edge of the solar system. That object, the Voyager probe, is traveling 38,000 mph (61,000 kph). While that might sound speedy, it's no match for interstellar distances.

For a true interstellar mission, scientists will have to develop new means of propulsion, such as nuclear-powered engines.

Project Icarus

One group working on the problem is Project Icarus, a joint endeavor by the Tau Zero Foundation and the British Interplanetary Society, to design an interstellar spacecraft. This first potential mission would not carry humans onboard, but would aim to send robotic probes to investigate a nearby star and its environs.

"The way to view it would be an incremental approach," said Icarus designer Ian Crawford, a planetary scientist at Birkbeck, University of London. "We would probably stick with a closer target initially to develop the expertise of interstellar spaceflight. Then you can move on to more distant targets. I don't think it's wise to bite off more than you can chew initially."

Project Icarus has chosen to give itself a deadline of 100 years, meaning the spacecraft must be able to reach its destination within a century, preferably sooner, of launching. [Most Extreme Human Spaceflight Records]

The Icarus designers are focusing on building a nuclear-powered spacecraft, which they hope would be able to travel at up to 15 percent the speed of light (light travels at 186,000 miles per second, or 300 million meters per second). At that rate, the farthest the Icarus spaceship could reach in 100 years would be about 15 light-years away.

That still leaves plenty of options.

Top candidates

Within 15 light-years of the sun, there are 58 known stars in 38 separate stellar systems (many of the stars are in binary pairs). Of those 58 stars, two are currently known to have planets.

However, because extraterrestrial planet-hunting is just heating up, scientists expect many of the others also host planets that just happen to be currently undetectable.

However, even the two nearest stars known to have planets are still good initial candidates.

One is called Epsilon Eridani, and lies 10.5 light-years away. It is known to have a planet that weighs about 1 1/2 times the mass of Jupiter, and also has a disk of dust around it that suggests there are likely other, smaller planets present, too.

The second candidate is called GJ 674. At 14.8 light-years away, this one is pushing right up against the 15-light-year limit, but it could still be a viable option, experts said.

And don't forget Alpha Centauri. Though no planets have yet been discovered around this star, that doesn't mean there aren't any.

"My own view is that Alpha Centauri will only lose its place at the top of the list if we determine that it doesn't have a planetary system," Crawford said.

The science of detecting alien planets is developing quickly, and researchers will probably have a much better idea where the nearby planets are by the time the first interstellar spaceship is ready to fly.

"The main thing to note here is that long before we can build an Icarus vehicle, astronomical tools will have told us where the planets are orbiting nearby stars," Crawford said. "Within 100 years, I'm reasonably confident we'll have a complete inventory. I think the take-home message here is, by the time we're ready to build an interstellar vehicle, we will in fact know where to send it."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.