Top 5 Nobel Prize Goof-Ups

This week, the Nobel Prize committees are announcing their picks for the 2011 prizes in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, economics, literature and peace.

We've made our own picks of the worst decisions in the history of the venerable institution. [See gallery of goofs]

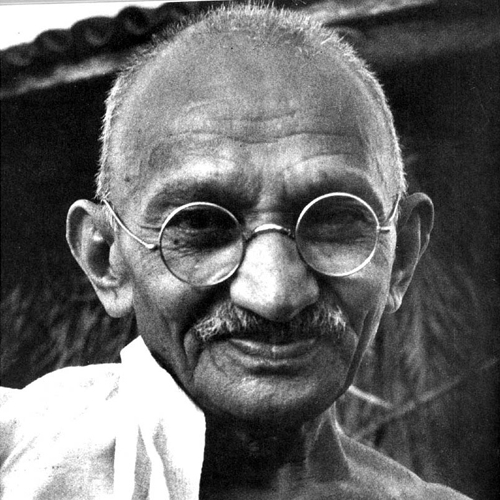

No Peace for Gandhi

Though he was nominated five times (including in 1948, just days before his assassination), the Indian spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2006, Geir Lundestad, secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, said, "The greatest omission in our 106-year history is undoubtedly that Mahatma Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize. Gandhi could do without the Nobel Peace Prize. Whether Nobel committee can do without Gandhi is the question." In 1948, the year of Gandhi's death, the Nobel committee declined to award a peace prize at all on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year. (The Nobel committee does not award its prizes posthumously.)

Gandhi's greatest achievement was his introduction of a method of nonviolent opposition in the Indian struggle for human rights. The method, "satyagraha" (Hindi for "truth force"), held that, without rejecting the rule of law in principle, Indians should peacefully break those laws that were unreasonable or suppressive. ['Face of Gandhi' Found On Google Mars]

Lobotomies for the win

In 1949, the Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his development of the prefrontal lobotomy — a procedure in which the connection is cut to a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex in mentally ill, depressed or learning disabled people. As the procedure can send patients into a vegetative state, lobotomies are now believed to be wildly unethical.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moniz first started performing lobotomies on humans back in 1936. He judged the results acceptable in the first 40 patients he treated, claiming: "Prefrontal leucotomy [his term for lobotomy] is a simple operation, always safe, which may prove to be an effective surgical treatment in certain cases of mental disorder." [The 6 Craziest Animal Experiments]

Admitting that some behavioral and personality deterioration often occurred in lobotomized patients, Moniz thought these side effects were outweighed by a reduction in the debilitating nature of mental illness. Not all his patients agreed. In 1939, Moniz was shot by a disaffected patient and subsequently needed to use a wheelchair.

When Moniz's procedure was improved upon in the 1940s by an American physician named Walter Freedman, it enjoyed a brief vogue, leading to Moniz's receipt of the 1949 Nobel Prize. About 20,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States before the procedure fell into disrepute several years later.

Honoring Arafat

In 1994, the Nobel Peace Prize committee honored Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat, for their efforts toward negotiating peace between Israel and Palestine in a series of meetings that took place in Oslo the year before. They were given the Nobel Peace Prize despite the fact that they had not managed to come to any workable agreement in those meetings.

According to historian Burton Feldman in "The Nobel Prize: A History of Genius, Controversy, and Prestige" (Arcade, 2000), when the Nobel committee voted to give Arafat the peace prize, one of its members promptly resigned and "publicly denounced Arafat as a terrorist."

Indeed, Arafat had previously engaged in many high-profile acts of terrorism against Israel, and presided over Palestinians as they continued to do so in later years until his death in 2004, according to his obituary in the New York Times.

Literary losers

Nobel Prize founder Alfred Nobel stated in his will that the literature prize ought to be awarded to an author who has produced "in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction." In the early years of the award (1901 to 1912), the Nobel selection committee interpreted this phrasing to mean writers who were advocating a lofty idealism.

For this reason, the committee did not recognize some of the most renowned authors of the time — and indeed, all time — such as James Joyce, Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, Marcel Proust, Henrik Ibsen and Mark Twain, whose works were deemed pessimistic and dystopic.

These literary legends died before the committee loosened its interpretation of Nobel's will, taking his words to mean "works of lasting literary merit."

Mendeleev tabled

The periodic table of the elements is one of the most useful — and surely the most famous — tools in all of chemistry. The great insight of the original table's creator, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, was in organizing the elements according to their atomic weights. Doing so revealed patterns in their properties: All chemical elements in the right-most column, for example, are "noble gases" that don't easily form chemical bonds with anything else. Furthermore, the elements in the middle region of the table are all metals. Using his periodic table, Mendeleev made many useful deductions about the nature of matter, and was even able to predict the properties of as-yet undiscovered elements. [Why Did Gold Become the Best Element for Money?]

However, despite the fact that Mendeleev lived until 1907, six years after the start of the Nobel Prize in chemistry, he was not recognized. In "The Road to Stockholm: Nobel Prizes, Science, and Scientists" (Oxford, 2002), István Hargittai claims this was because of behind-the-scenes machinations by a member of the Nobel selection committee who disagreed with Mendeleev's work.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow us on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.