3 Weird Alien Planets Found Around Sun-Like Star

A NASA spacecraft has found an unusual three-planet system that consists of one super-Earth and two Neptune-size worlds orbiting a star similar to our sun, a new study reveals.

The planet-hunting Kepler Space Telescope discovered the three planets around the star Kepler-18, which is only 10 percent larger than the sun and contains 97 percent of the sun's mass, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin said. The alien system could also host more planets than have been found so far, they added.

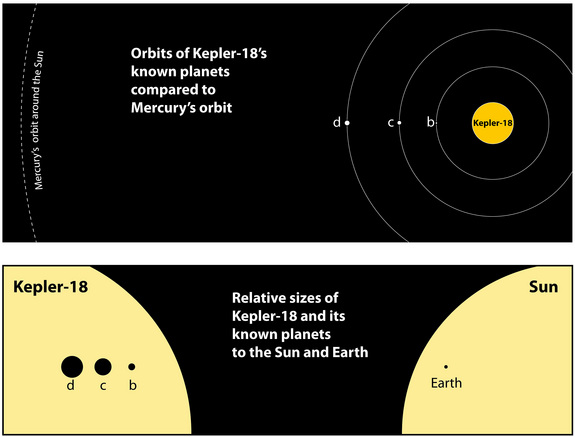

All three planets, which are designated Kepler-18b, c, and d, orbit much closer to their parent star than Mercury does to the sun. The planet Kepler-18b orbits closest to the star, taking 3.5 days to complete its journey. The planet is about 6.9 times the mass of Earth and is twice the size of our home planet, making planet b a so-called super-Earth, the researchers said.

Kepler-18c, which takes 7.6 days to orbit the star, is about 5.5 times larger than our planet, and has a mass equivalent to about 17 Earths. Kepler-18d has a 14.9-day orbit and is about seven times the size of Earth, with a mass of about 16 Earths. According to these figures, planets c and d qualify as low-density "Neptune-class" worlds, the researchers said. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

The findings were presented Tuesday (Oct. 4) at a joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Science in Nantes, France. The study will be published in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series in November.

Scanning the cosmos

NASA's Kepler spacecraft hunts for exoplanets using the transit method, which looks for periodic dips in a star's brightness over time that could indicate a planet is passing in front of it from the telescope's perspective. The alien worlds around Kepler-18 were found using this method, but the orbits of the planets themselves were a point of interest to the researchers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kepler-18c orbits its parent star twice for every one orbit that Kepler-18d makes, explained study leader Bill Cochran of The University of Texas at Austin. But the two planets do not cross the face of their parent star at these same orbital periods.

"One is slightly early when the other one is slightly late, [then] both are on time at the same time, and then vice-versa," Cochran said in a statement.

This suggests that Kepler-18c and Kepler-18d are engaged in something of an orbital dance.

"It means they're interacting with each other," Cochran said. "When they are close to each other … they exchange energy, pull and tug on each other."

Once Kepler identifies potential exoplanet candidates using the transit method, scientists around the world use ground-based telescopes to collect more data and try to separate real findings from any false positives. [10 Real Alien Worlds That Could Be In 'Star Wars']

The Kepler-18 system

The planets around Kepler-18 helped astronomers out because the orbital activity between Kepler-18c and Kepler-18d indicated that they must belong to the same planetary system. But, proving the identity of Kepler-18b, the super-Earth, turned out to be a bit more complicated, Cochran said.

The team of astronomers used a technique called "planet validation," in which they examined the probability that the cosmic body could be something other than a planet. The researchers first analyzed high-resolution images of the space around the Kepler-18 star to see if the transit signal could have been caused by background objects in the vicinity.

"We successively went through every possible type of object that could be there," Cochran said. "There are limits on the sort of objects that can be there at different distances from the star. There's a small possibility that [Kepler-18b] is due to a background object, but we're very confident that it's probably a planet."

In fact, Cochran and his colleagues calculated that it is 700 times more likely that Kepler-18b is a real planet rather than a background object.

Identifying alien planets

The researchers said that this method of planet validation could play an important role in the ongoing hunt for habitable alien planets.

"We're trying to prepare the astronomical community and the public for the concept of validation," Cochran said. "The goal of Kepler is to find an Earth-size planet in the habitable zone [where life could arise], with a one-year orbit. Proving that such an object really is a planet is very difficult [with current technology]. When we find what looks to be a habitable planet, we'll have to use a validation process, rather than a confirmation process. We're going to have to make statistical arguments."

To date, Kepler has found 1,235 planetary "candidates" that are awaiting confirmation through follow-up observations. Researchers have estimated that at least 80 percent of these will be verified as real planets.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.