Why Arnold's Self-Statue Is Very Serious. Really.

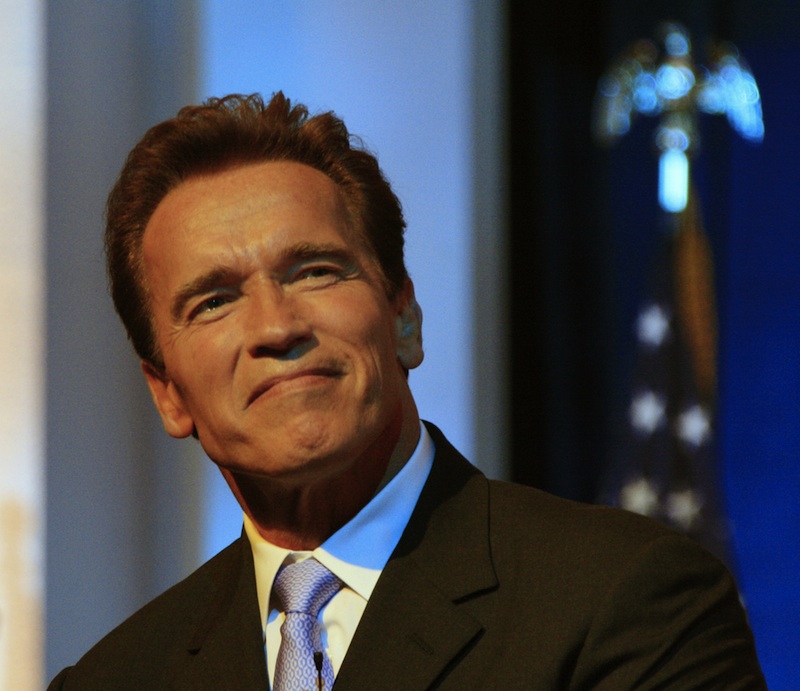

Photographs of former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger grinning next to a self-commissioned, larger-than-life bronze statue of himself in his body-building days may be eyebrow-raising, but social scientists say that Schwarzenegger is simply following a trend laid down by thousands of years of human history.

"It's the kind of thing that we really have been doing since the ancient Greeks," archaeologist and historian Lemont Dobson of Drury University in Missouri said in a phone interview with LiveScience. "You get a wealthy, powerful, political social leader who is — oh, God, I just saw the bronze statue."

Okay, so the representation of a young, flexing Schwarzenegger in a Speedo-like swimsuit, veins bulging, is not exactly Lincoln Memorial-style statuary. Commissioned by Schwarzenegger as one of a trio of identical statues, the bronze bodybuilder now resides at a museum dedicated to the ex-governor in his hometown of Thal, Austria. Schwarzenegger attended the inaugurating of the museum today (Oct. 7), according to the AP.

Psychology experts concede that commissioning an 8- to 9-foot (3-meter) tall statue of oneself is likely a symptom of some level of egotism. But the rich and famous have long lionized themselves, and Schwarzenegger is a guy with a lot of name recognition.

"This is not some guy who lives in the village who made a statue of himself," said Josh Klapow, a psychologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. "This is one of the most well-known athletes, actors and politicians in the world … Sometimes the actions are proportional to the individual."

The history of self-promotion

Schwarzenegger is far from alone in his apparent desire to see himself immortalized in his best light.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"From ancient Chinese emperors creating terra cotta warrior armies to the pharaohs and their pyramids to the ancient Greeks creating statues to commemorate their athletic prowess to Donald Trump building skyscrapers across the country with his name on them, I think as human beings, we just can't help ourselves," Dobson said.

Traditionally, Dobson said, monuments have worked to communicate images of power, valor and success to the little people. [Album: The 7 Wonders of the Ancient World]

"It certainly is a PR campaign," he said.

And forays into public relations may also help consolidate power and prestige for a leader's children, said University of Michigan evolutionary psychologist Dan Kruger.

"Basically, by setting up this mythos of divine ancestry and lineage, your future descendents can benefit greatly from that," Kruger told LiveScience. "I don't know if Arnold is consciously recognizing this, but that has been the effect throughout human history."

Schwarzenegger may also have less self-centered reasons for commissioning the statue and participating in the museum dedication, Kruger added. He might be motivated to give back to his small hometown by providing an attraction to bring in tourism dollars.

Buff and bronzed

Even the physicality of the Arnold statue has roots in history. In the early 1800s, for example, sculptor Antonio Canova created a likeness of a svelte, nude Napoleon in the guise of the Roman god Mars — though Napoleon himself disliked the statue and banned it from public view.

In Schwarzenegger's case, the muscle-bulging statue isn't much of an exaggeration, Klapow said.

"If you're going to make a statue of yourself that is going to appear in public, I don't think it's unreasonable to have that statue represent you in the most favorable light," Klapow said. "And Arnold Schwarzenegger in his most favorable light is one of the most muscle-bound individuals on the face of this Earth."

But with the glory of fame and self-aggrandizement come the slings and arrows of mockery from those less fortunate.

"I can see someone in ancient Rome scoffing and rolling their eyes at the latest statue of Caesar, going, 'Oh, God, here he goes again,'" Dobson said. "Periodically, people would deface these kinds of things. We didn't invent graffiti, and we didn't invent mocking the rich and powerful."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.