Caribbean Hurricanes Cluster, Letting Coral Reefs Mend

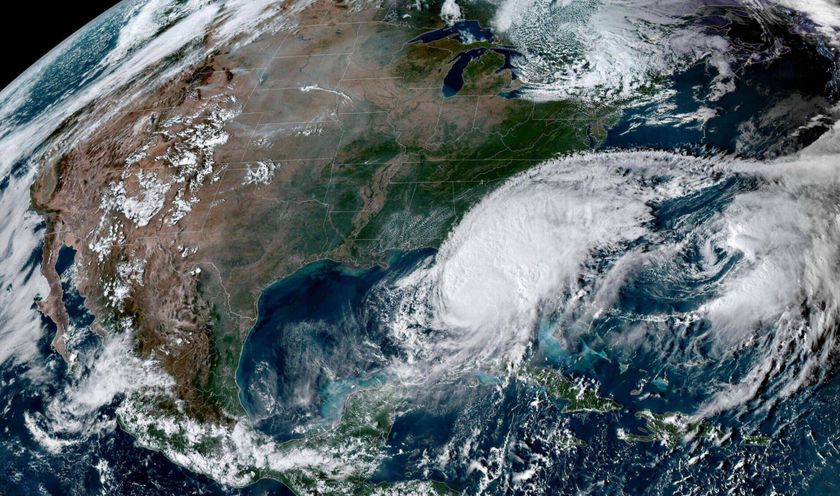

Hurricanes in the Caribbean tend to cluster together during intense periods of action, sending one storm after another across the body of water, a new study finds.

While this may not be good news for island dwellers, it may not be bad for another key Caribbean denizen, the coral reef, the study suggests.

Tropical cyclones (a category that encompasses tropical storms and hurricanes) have a massive economic, social and ecological impact on the places they hit. Models of their occurrence influence many planning activities such as setting insurance premiums and coastal conservation. Understanding how often tropical storms and hurricanes form, and the patterns in which they do, is important for people and ecosystems along vulnerable coastlines.

In the new study, scientists mapped the variability in hurricanes throughout the Americas using a 100-year historical record of hurricane tracks.

Short intense bursts of hurricanes followed by relatively long quiet periods were found around the Caribbean Sea. The clustering was particularly strong in Florida, the Bahamas, Belize, Honduras, Haiti and Jamaica.

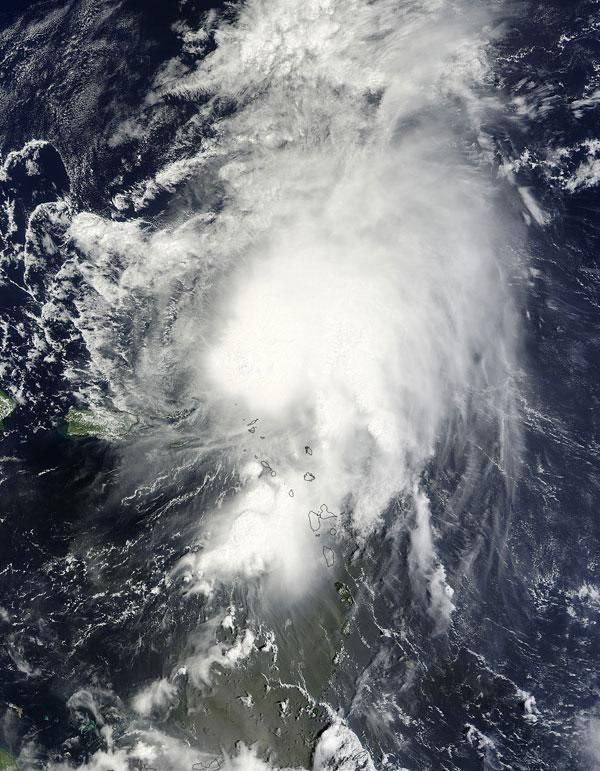

Clusters and coral reefs

This clustering can be tough on coastal communities because they don't get a chance to recover from one storm before another one hits. But modeling of Caribbean coral reefs found that clustered hurricanes are actually less damaging for coral reef health over the long term than random hurricane events. That's because the first hurricane to hit a reef always causes a lot of damage, but then those storms that follow in quick succession don't add much additional damage as most of the fragile corals were removed by the first storm.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The following prolonged quiet period after a hurricane cluster allows the corals to recover and then remain in a reasonable state prior to being hit by the next series of storms.

"We didn't at first expect clustering to have advantages, but this study has clearly shown that clustering can help by giving ecosystems more time to recover from natural catastrophes," said study team member David Stephenson of the University of Exeter.

Other impacts

Of course, the news isn't all good for coral reefs, which are experiencing pressures beyond the ones that storms exert.

"Cyclones have always been a natural part of coral reef lifecycles," said study team member Peter Mumby of the University of Queensland. "However, with the additional stresses people have placed upon ecosystems like fishing, pollution and climate change, the impacts of cyclones linger a lot longer than they did in the past."

It is important to consider the clustered nature of hurricane events when predicting the impacts of storms and climate change on ecosystems, according to the study. For coral reefs, forecasts of habitat collapse were overly pessimistic and have been predicted at least 10 years too early as hurricanes were assumed to occur randomly over time, which is how most research projects model the incidence of future hurricanes, said the researchers.

The findings were published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.