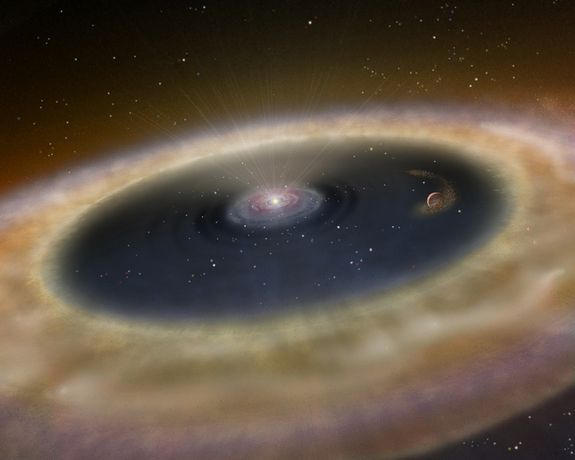

Astronomers have photographed the youngest exoplanet ever found, spotting the alien world as it is still forming out of the dusty disk around its parent star, a new study reports.

Researchers used Hawaii's Keck Observatory to capture the first direct images of a planet in the process of forming around its star. The newly born object, which astronomers are calling LkCa 15 b, appears to be a hot "protoplanet" that is sucking up a surrounding swath of cooler dust and gas.

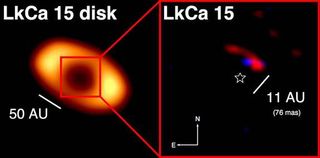

The new images from Keck reveal that the alien planet sits in a wide gap between its host star and an outer disk of dust, the researchers said.

"LkCa 15 b is the youngest planet ever found, about five times younger than the previous record holder," study lead author Adam Kraus, of the University of Hawaii, said in a statement. "For the first time, we’ve been able to directly measure the planet itself as well as the dusty matter around it." [See photos of dusty disk for planet LkCa 15]

Finding a newly forming planet

The newly forming planet is a relatively close neighbor to Earth; it's located only about 450 light-years away in the constellation Taurus (the Bull). But spotting it wasn't easy.

Astronomers relied on Keck's adaptive optics capability, which incorporates a deformable mirror to correct for distorted starlight caused by our atmosphere. They then canceled out bright starlight using a technique called aperture mask interferometry, which involved placing a mask with several holes in the path of the light collected by Keck.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These methods allowed the team to resolve the protoplanetary disk around the star LkCa 15, and to see the gap in the disk where the baby planet was lurking.

"Interferometry has actually been around since the 1800s, but through the use of adaptive optics has only been able to reach nearby young suns for about the last seven years," said study co-author Michael Ireland of Macquarie University and the Australian Astronomical Observatory. "Since then, we’ve been trying to push the technique to its limits using the biggest telescopes in the world, especially Keck."

The researchers discovered LkCa 15 b after initiating a survey of 150 young dusty stars, which led to a more concentrated study of a dozen stars. They hit the jackpot early.

"LkCa 15 was only our second target, and we immediately knew we were seeing something new," Kraus said. "We could see a faint point source near the star, so, thinking it might be a Jupiter-like planet, we went back a year later to get more data." [The Strangest Alien Planets]

Kraus presented the results today (Oct. 19) at a meeting at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The discovery will also be published in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

A big baby

As far as infants go, LkCa15 b looks like a whopper, perhaps harboring as much mass as six Jupiters. But since the planet is still forming, it could end up being considerably smaller, Kraus explained.

"A lot of the light that we’re seeing from this object could be released by this material falling on it," he said. "So, six Jupiter masses should really be regarded as an upper limit. It may be that very little of the light is coming from the planet, and it could be much less massive."

However big it is, the alien world is definitely young. Its parent star, which is about as massive as the sun, is only about 2 million years old, Kraus said.

Astronomers have long surmised that baby planets carved out the gaps they've observed in young stars' dusty disks. Now that they've demonstrated the ability to spot one such infant world, scientists could soon start detecting many more.

"This is exciting because we look at them [the gaps] and know there’s a planet there," Kraus said. "We know from the location of the gap where the planet is likely to be sitting, and it’s just a matter of looking at them and finding a way to detect these planets."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow contributed to this story.You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.