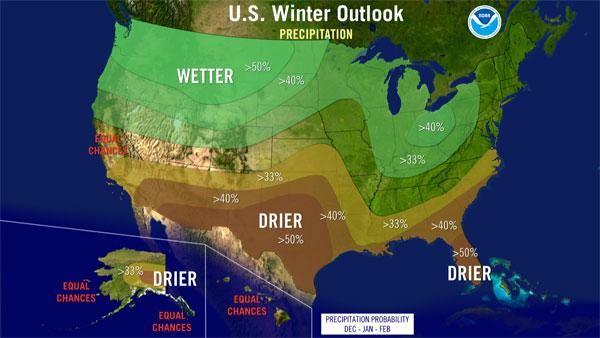

Southern Drought to Continue This Winter (Thank La Niña)

There's little relief in sight for the drought-plagued states of the Southwest and the southern Plains, which will continue to see drier and warmer-than-normal conditions this winter, government scientists said today (Oct. 20) as they issued their annual winter weather outlook for the country.

The redevelopment of La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean, with ocean temperatures 1 to 2 degrees Fahrenheit (0.6 to 1.1 degrees Celsius) lower than normal, will have a big influence on this year's winter weather, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said.

"The evolving La Niña will shape this winter," said Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. The colder-than-average waters that signal a La Niña can have impacts on the climate patterns of areas around the globe, just as the warmer-than-average Pacific waters that signal an El Niño do.

NOAA expects La Niña, which returned in August, to gradually strengthen and continue through the upcoming winter.

"We're fairly confident that this La Niña isn't going anywhere and it will be with us through the winter," Halpert told reporters during a telephone conference. [Click here to see your region's winter outlook.]

Drought woes

With La Niña in place "it's most likely that severe drought will continue" in Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico and parts of surrounding states, Halpert said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Texas has been at the epicenter of a historic and catastrophic drought. The state experienced its driest 12-month period on record from October 2010 through September 2011. Some 91 percent of Texas is under extreme or exceptional drought, the two highest classifications of dry conditions.

About 81 percent of Oklahoma and 63 percent of New Mexico are in these categories, along with smaller, but significant, portions of neighboring states from Arizona to Louisiana, said David Brown, director of Southern Region Climate Services. [Related: 10 Driest Places on Earth]

"I think it's fair to say that Texas and Oklahoma have been at the epicenter of this drought, probably in that order," Brown said.

Officials and forecasters had hoped that the predicted active Atlantic hurricane season would bring substantial rains and some relief to the area. While some of the central Gulf Coast states did see some rain from these storms, the areas most at need of quenching saw virtually no impact.

Some frontal systems have passed through the parched areas, "but those really only constitute small dents" because they only brought modest amounts of rains to very localized areas, Brown said.

It would take around 10 to 15 inches (25 to 38 centimeters) of rain to make any dent in the drought — some areas of southeast Texas are more than 30 inches (76 cm) below their normal precipitation levels — and with La Niña in place and forecast to continue through the winter, "the likelihood of seeing that kind of relief is pretty low," Brown said.

The continuation of the drought also likely means that there will be a high risk of other extreme events, such as wildfires, which ravaged areas of Texas this year. The huge environmental and economic impacts from the drought will also likely be exacerbated, including crop and livestock losses, additional stresses to already heavily taxed groundwater systems and lost tourist dollars.

Brown gave the example of the community of Lake Travis outside of Austin, which has lost considerable business revenues because the nearby lake of the same name is 30 feet (9 m) below normal and recreation and tourism is down substantially.

In addition to the continuation of the drought in the areas already experiencing it, some parts of the Gulf Coast and Florida could see drought conditions develop this winter, according to the current forecast.

Wild card

One factor that could prove to be a wild card in the current outlook is the lesser-known and less- predictable climate phenomenon called the Arctic Oscillation, which could produce dramatic short-term swings in temperatures this winter, as it has in winters past.

"The erratic Arctic Oscillation can generate strong shifts in the climate patterns that could overwhelm or amplify La Niña's typical impacts," Halpert said in a statement.

The Arctic Oscillation is always present and fluctuates between positive and negative phases. The negative phase of the Arctic Oscillation pushes cold air into the United States from Canada. The Arctic Oscillation went strongly negative at times the last two winters, causing outbreaks of cold and snowy conditions in the country, such as the "Snowmaggedon" storm of 2009. Strong Arctic Oscillation episodes typically last a few weeks and are difficult to predict more than one to two weeks in advance.

The Arctic Oscillation could switch up and bring a repeat of the last couple of winters. Or not.

"It really is a wild card that at this point," Halpert told reporters.

Stormy periods can occur anytime during the winter season. To improve the ability to predict and track winter storms, NOAA implemented a more accurate weather forecast model for this year that it tested out last year. The model will allow forecasters to better track small-scale features like bands of snow and better predict localized variations in snowfall, said Bob Kelly, chief of forecast operations at the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center in Camp Springs, Md.

This seasonal outlook does not project where and when snowstorms may hit or provide total seasonal snowfall accumulations. Snow forecasts are dependent upon winter storms, which are generally not predictable more than a week in advance.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.