Doomed Polar Explorer's Lost Photos Revealed

One hundred years after British explorer Robert Falcon Scott set out on his doomed journey to the South Pole, many of his own photographs of Antarctica are being published for the first time in a new book — written by a descendent of one the men who perished by his side.

Of the 100 or so photographs published in "The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott," (Little, Brown and Co., 2011), out in the United States this week, many have never been shown publicly, and might have never have been, were it not for a conversation over a cocktail in a London barroom, according to the book's author, David M. Wilson.

A few years ago, Wilson was enjoying a post-auction drink with a friend in the business, a dealer in polar artifacts, who hinted he'd come upon some particularly tantalizing items. Finally, he relented, and gave up his secret.

"He told me he had the lost photographs of Scott and I nearly choked on my gin and tonic," Wilson told OurAmazingPlanet. [See some of the photos here.]

Polar relations

Although several of Scott's own photographs from his ill-fated 1910 to 1912 Antarctic expedition had been published, most of them never saw the light of day, Wilson said.

Herbert Ponting, the expedition's official photographer, didn't accompany Scott to the pole, and survived to bring Scott's photos, along with his own iconic images of the expedition, back to England; however, the majority of Scott's photographs had lain in a disorganized jumble for decades, lost in a photo agency's basement. The photos resurfaced in 2001, but, poorly labeled and poorly publicized, they'd languished in relative obscurity until they landed in the hands of the London auction house.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

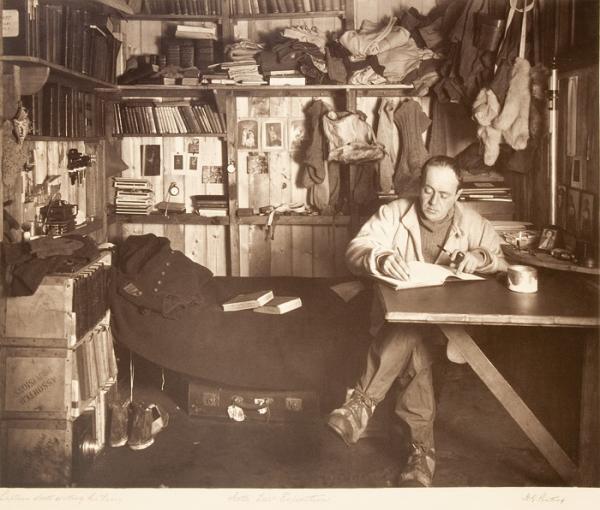

Fast forward several years, and the photographs, after a painstaking cataloging effort, are labeled and reproduced as large black-and-white prints in a handsome coffee-table book. Its author's interest in the subject matter is more than historical curiosity. His grandfather's brother Edward Wilson appears in many of the photos. He died by Scott's side in a tiny tent on the lonely Antarctic ice after an arduous journey that had already offered a full measure of heartbreak.

Frozen trek

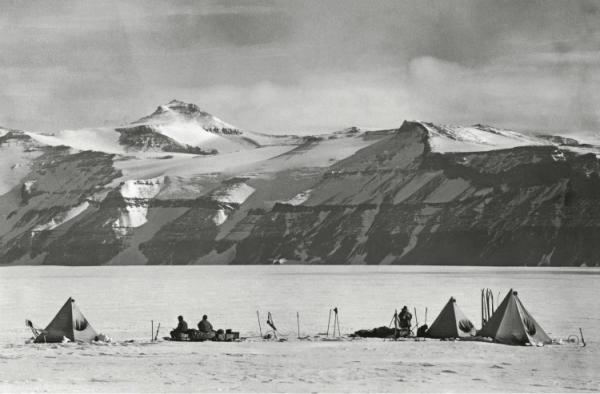

Although Scott did reach the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912, after a two-and-a-half month slog, he and his four companions discovered they weren't the first to arrive. A tent, with a dark flag fluttering above it, stood at the spot. Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had gotten there first, a full month earlier, on Dec. 14, 1911, and left behind the makeshift monument, along with a note addressed to Scott.

Faced with ferocious blizzards and dwindling supplies, Scott and his party never made it home. He met his end in late March, freezing to death alongside his two remaining men, Henry "Birdie" Bowers and Wilson, a doctor and an artist brought along to record the unexplored continent's geology and geography, and Scott's dear friend. (Two of their party succumbed earlier: Petty Officer Edgar Evans was done in by injury, and, hobbled by frostbite, Lawrence Oates famously sacrificed himself by walking out alone into a snowstorm.) [The Harshest Environments on Earth]

Their frozen bodies were found months later, along with Scott's diary, which recounted the men's struggle up until the end, Wilson's sketches, and photographs Bowers took.

"At the end of the day, this is one of the greatest stories of human exploration history, full stop," said author David M. Wilson, who said that although Scott's story is well-known, the photographs reveal a side of the man largely unseen.

Polar ambitions

"He had an artistic side and he had a natural eye," Wilson said. In addition, the photographs are unedited, he said, "so you have the photographs from the humble beginnings."

After his sledding party left the relative comfort of the expedition base, Scott even began experimenting with images that his teacher, the master photographer Ponting, rarely attempted, such as action shots and panoramas, Wilson said.

"All these sorts of things started appearing, but they also bring the emphasis back onto the scientific work," Wilson added.

Scott's and Ponting's photos of Antarctica represent a transition in expedition science, which had relied on artists like Edward Wilson to make a record of discoveries.

"You've got this point where the camera takes over from the sketch pad as the best scientific record, and it happened on this expedition," Wilson said.

However, although Scott did bring along scientists — who took invaluable Antarctic data — at great cost to himself, he didn't bring the cameras in the name of science alone, according to Ross MacPhee, curator of vertebrate zoology at the American Museum of Natural History, and author of the book, "Race to The End: Amundsen, Scott, and the Attainment of the South Pole" (Sterling Innovation, 2010). Scott was also a savvy advertiser.

"Scott understood the importance of bringing back images, because people emotionally react to images in ways that they often don't to words," MacPhee said.

As to Scott's ultimate motivations, which have been both deified and demonized in the intervening decades, MacPhee said they were complex.

"Scott would surely have liked to win — he did, after all, stake his life on it — but there was more to his being in Antarctica than just striving to be the first to stand at the South Pole," MacPhee said. "He did very much want to have his expeditions remembered as being primarily driven by science rather than by adventure."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Andrea Mustain on Twitter: @andreamustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.