A still-forming alien solar system has enough water in its outer reaches to fill Earth's oceans several thousand times over, a new study finds.

The discovery marks the first time astronomers have detected water in a dusty planet-forming disk so far from its central star, in the frigid region where comets are born. Scientists think comet impacts delivered most of Earth's water, and the new study hints that alien planets may commonly acquire oceans in the same way.

"We now know that large amounts of water ice are available in planet-forming disks, ready to be incorporated in comets," said Michiel Hogerheijde, of Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, the study's lead author. "Ultimately, some of this water may end up on Earth-like planets that form completely dry but this way may end up with life-supporting oceans." [The Strangest Alien Planets]

A nearby star

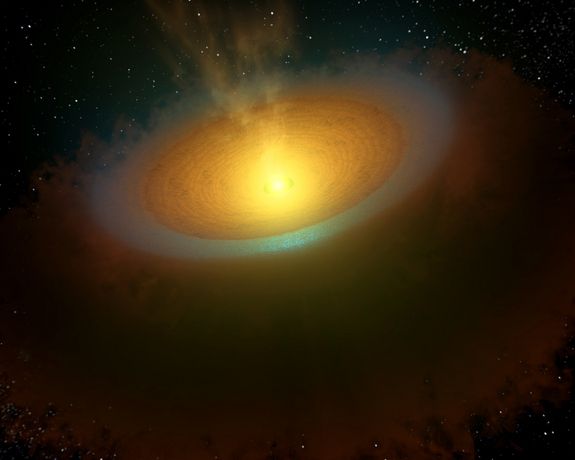

Hogerheijde and his team made the find using the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory. They trained Herschel on the appropriately named young star TW Hydrae, which is located about 175 light-years away in the constellation Hydra (the Sea Serpent).

TW Hydrae is an orange dwarf star, slightly smaller and dimmer than our sun. It's only about 10 million years old, and is still surrounded by a disk of dust and gas that should one day coalesce to form planets, researchers said.

Herschel detected huge amounts of water — thousands of times more water than is found on Earth — in the freezing-cold outer reaches of this disk, far from TW Hydrae itself. The water out there is likely ice coating the innumerable tiny dust grains that swirl around in the disk, researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ultraviolet radiation from TW Hydrae knocks some water molecules free from these icy grains, allowing Herschel to spot the light signature from the resulting vapor.

Astronomers have found water vapor in the warmer, interior regions of other planet-forming disks before. So Hogerheijde's team wasn't shocked to find evidence of water farther out.

"We had actually always suspected that this much water was hiding out in the cold reaches of disks like these," Hogerheijde told SPACE.com in an email. Thanks to Herschel, he added, "we can now for the first time detect the water vapor, and infer the presence and size of the hidden ice reservoir." [Gallery: Views from the Herschel Space Observatory]

The team reports its results in the Oct. 21 issue of the journal Science.

Alien comets, alien oceans?

The TW Hydrae find suggests that ice-bearing comets may form commonly around other stars. The icy wanderers might thus have seeded oceans on many alien planets throughout the cosmos over the years, researchers said.

"It does seem likely that life-supporting environments can form easily around other stars, now that we have found sufficient water ice to seed Earth-like planets with oceans," Hogerheijde said.

The discovery could also help astronomers better understand solar system evolution and planet formation in a general sense, he added.

For example, large quantities of ice in a protoplanetary disk could serve as a sort of glue, Hogerheijde said, helping dust grains stick together and grow into planetesimals, the building blocks of planets.

Also, analysis of TW Hydrae's far-flung ice shows that it's significantly different than that found on comets in our solar system. This suggests that comets' ice comes from several different regions in the dusty disk, not just the freezer on its outer edge.

"We actually think that comets in our own solar system contain mixtures of ices from across the solar nebula, hinting at the presence of long-range transportation of material through planet-forming disks," Hogerheijde said. "This is a much more 'dynamic' picture of planet formation than previously imagined."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.