Nature Under Glass: Gallery of Victorian Microscope Slides

In Awe of the Natural World

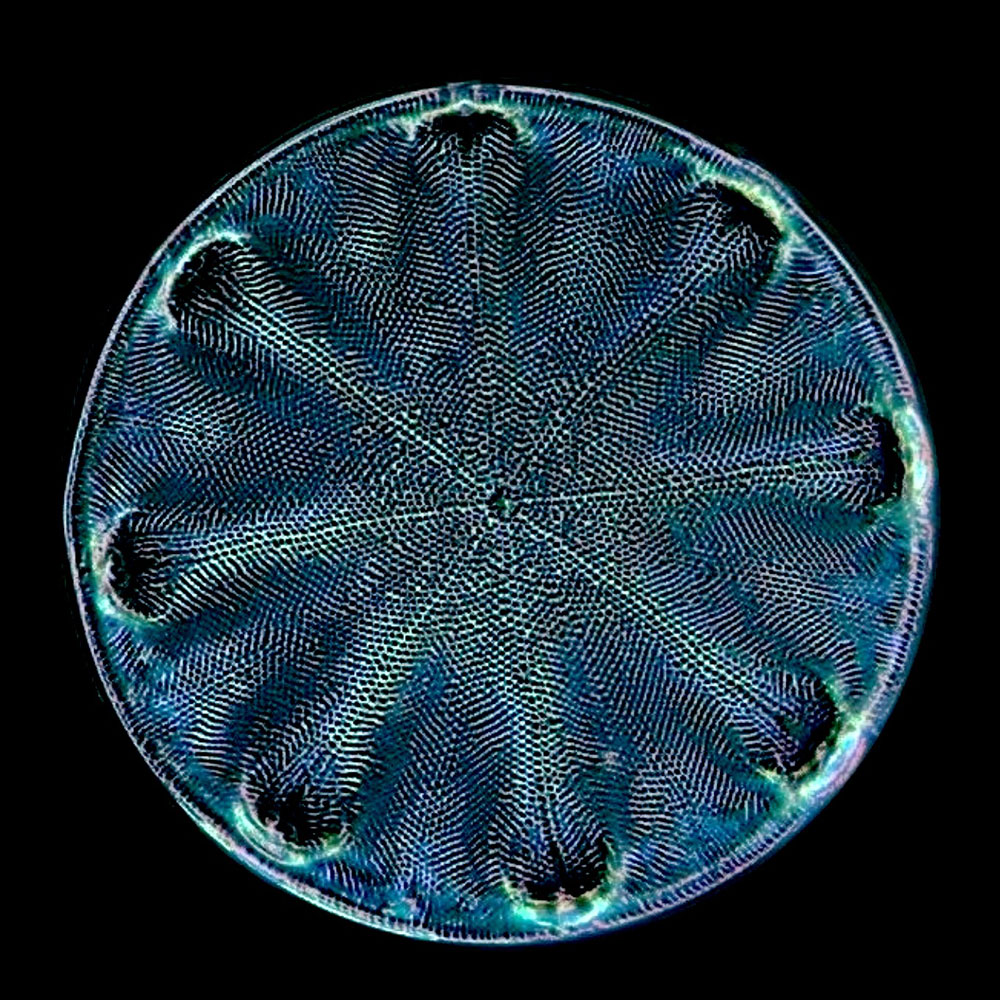

In the mid- to late-19th century, science gripped the public imagination. Literacy rates were rising, feeding demand for books. Theories, put forward in books like Charles Darwin's Origin of Species, about how the natural world came to be fascinated readers. Museums and exhibitions promoted interest in science and devices like the microscope. Microscopes became cheaper, and a popular form of entertainment. Viewers peered through them at specimens they'd collected themselves or slides prepared professionally. The image above shows an ocean-dwelling diatom — a single-celled alga surrounded by a glass-like cell wall.

Under Glass

The microscope slide containing the diatom indicates it was collected in Maryland and made by someone identified only as "FM," according to the slide's owner Howard Lynk, an antique slide collector who displays some of his collection on his website, Victorian Microscope Slides. He owns hundreds of slides from the 1830s to around the end of the century. A few are displayed within this gallery.

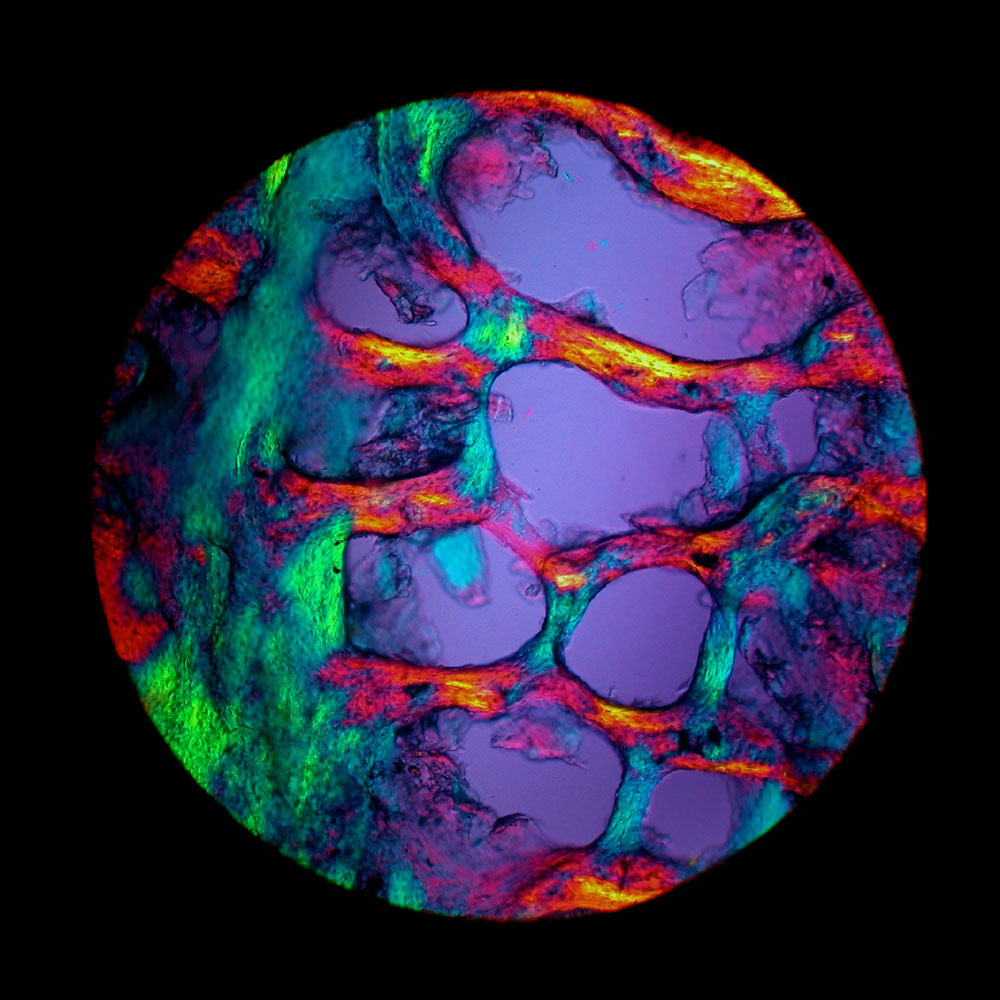

Simple Bone

To the naked eye, this sample looks like what it is, a sliver of bone from a porpoise's vertebrae. But, techniques commonly employed by Victorian microscopists, transform it.

Manipulating Light

Special filters used in the microscope transform the pale porpoise bone into the vibrant colors seen above. Polarizing filters eliminate certain wavelengths of light based on the direction in which they vibrate, and, when positioned correctly, they reveal special properties of the specimen, related to how the substance refracts, or bends, the light waves that enter it. This produces what's known as interference colors. An additional filter, made of the mineral selenite, further alters the behavior of light and changes the colors that the viewer sees.

Colorless Crystals

Like the porpoise bone, the ammonia sulfate crystals on this slide don't look like much to the naked eye.

A Different View

But crossed polarizing filters (called a Polariscope) reveal an entirely different sight.

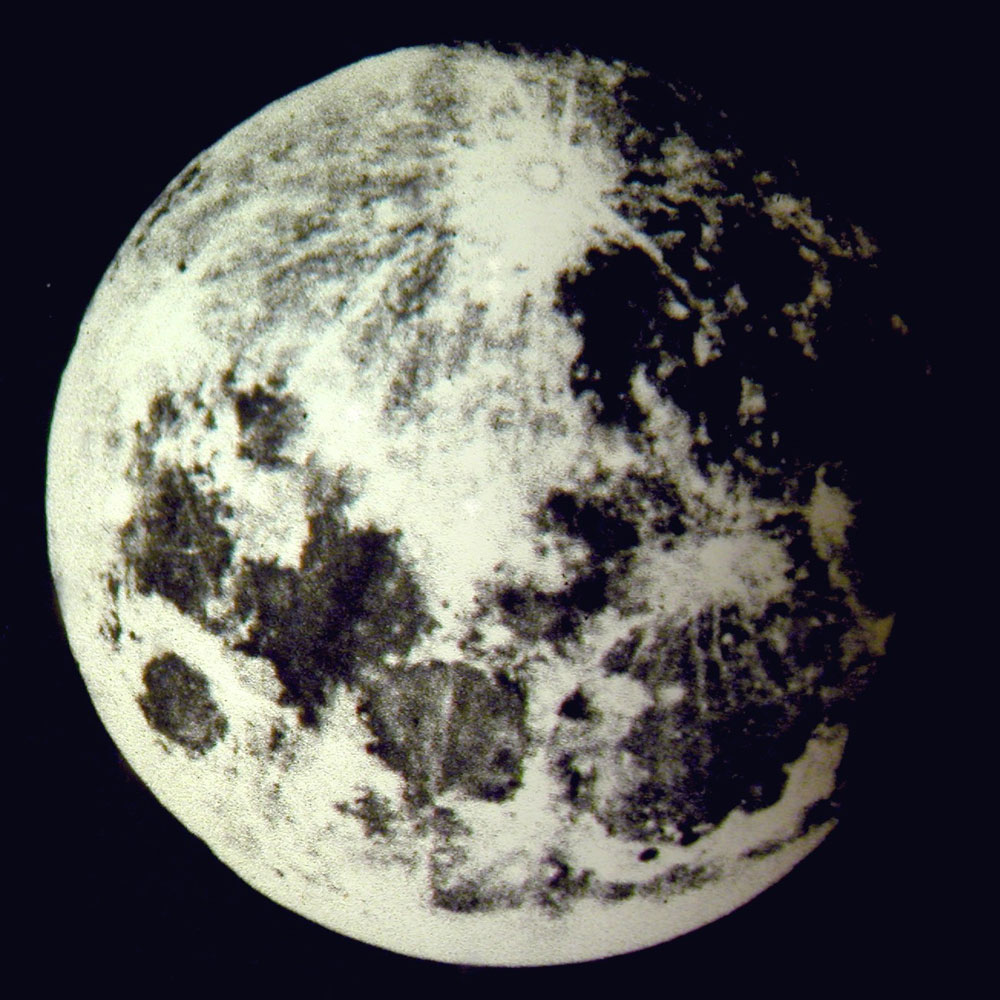

Moon Through the Microscope

A slide mounter and optician J.B. Dancer perfected the process for miniaturizing photos for microscope slides in the early 1850s. These slides depicted famous people, art, buildings, landmarks and, as shown above, the moon. This slide's maker is known only as 'E.M.'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A New Way of Seeing

A revolution in visual communication took place in the 19th century. Images — like book illustrations, panoramas and illusions — became more plentiful and popular. New technologies explored how we see, like the stereoscope, which recreates three-dimensional vision, and sights once available to only a few, like the view through a microscope or telescope, became widely available. Photography was invented in the first part of the century, then applied more to scientific subjects as time progressed, and the scientific study of the eye became important, according to Bernard Lightman, a professor of humanities at York University in Canada and author of the book Victorian Popularizers of Science (University Of Chicago Press, 2010). "People start to think more about the process of seeing, and what does that tell us about the natural world," Lightman said.

The Slide Evolves

In 1839, the Microscopical Society of London recommended two standard sizes for glass slides, and these quickly caught on. In earlier times, specimens were often mounted on sliders made of bone, ivory and hardwood. The sliders shown above are made of mahogany and shown with the viewer used to magnify them.

A Microscope for the Masses

This microscope was manufactured in 1856 by Smith & Beck, London. Up until the 1850s, a microscope was an instrument only the wealthy could afford. Around 1850, there was a concerted effort to manufacture a useful but relatively inexpensive microscope. Many people at the time believed that educating the general population would bring a greater appreciation of "God's Creation", and thus a more positive and beneficial society. The model shown above was one affordable for the burgeoning middle class, according to Lynk.

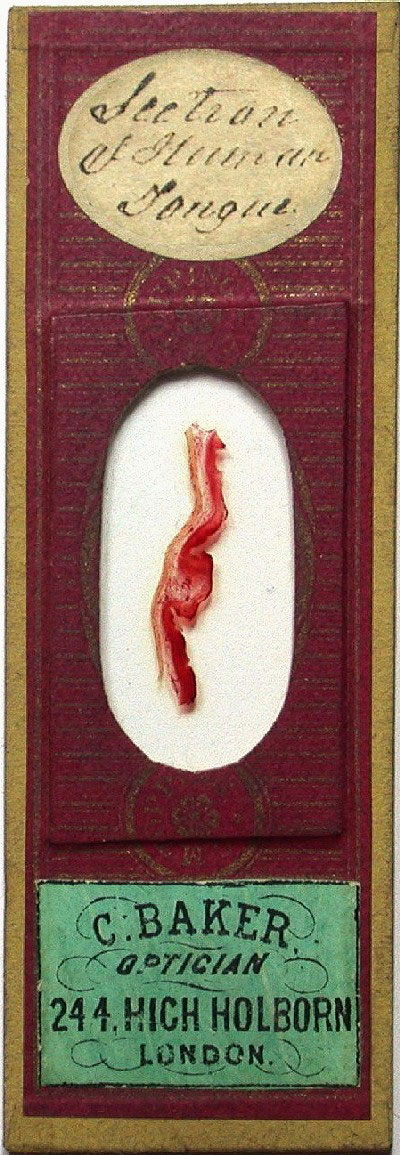

New Technology

Some slides, like the one above, reflected scientific developments of the time. Around the mid- to late-1850s, techniques were developed to dye specific structures within a preserved sample of once-living tissue. Similar approaches are still used today. Developed about the same time, a device called a microtome made it possible to cut much thinner sections of a specimen. Above, an ornately covered slide containing a section of human tongue.