Nature Under Glass: Gallery of Victorian Microscope Slides

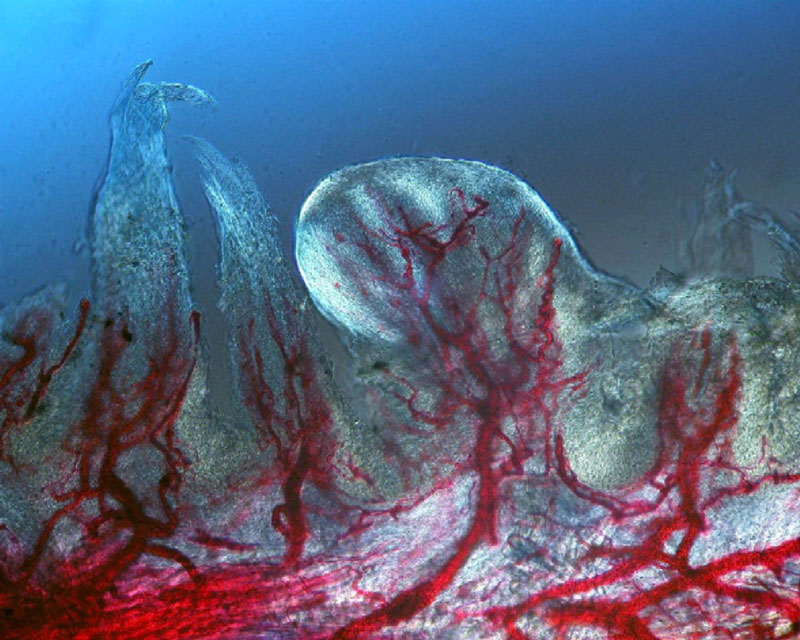

A Taste for Science

Red dye fills the tiny blood vessels of this tongue tissue. The large, roundish structure in the center of image is a projection on the surface of the tongue known as a fungiform papilla. These projections hold the taste buds, which are not visible in this image. The feather-like projections to the side are filiform papillae.

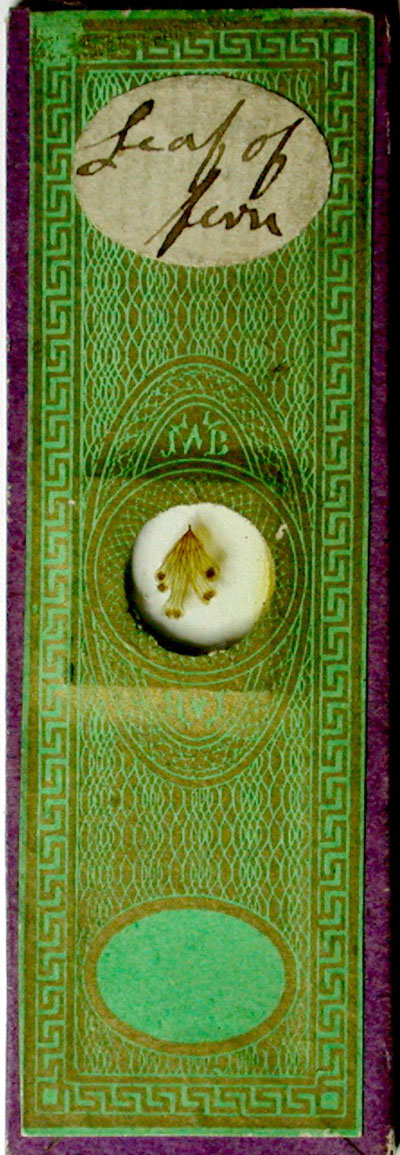

A Little Greenery

Ferns were another fad among Victorians. The craze was called "Pteridomania" or Fern Fever. Above, a Victorian-era fern leaf under a microscope. The slide gives no specific information about this fern, although its maker, J.W. Bond, was one of the pioneering early slide mounters, according to Lynk.

The Cover Up

Slide makers first used decorative paper covers on microscope slides — like the green and gold cover on this fern specimen — to hold the cover slip in place on the slide. Over time, the covers became more decorative, with patterns unique to their makers.

Insecticide

Slide makers prepared insects like these by using potassium hydroxide to remove their innards, while leaving the hard outer shell, called an exoskeleton, intact. These remains were imbedded in Canadian balsam, which is basically tree sap. Later slide mounters devised a way to preserve the entire insect, including its innards by mounting it within a well on the slide, according to Lynk.

Fuzzy, But Not Warm

A closer look at a preserved moth larva, mounted by Frederic Enock, a prominent maker of insect slides.

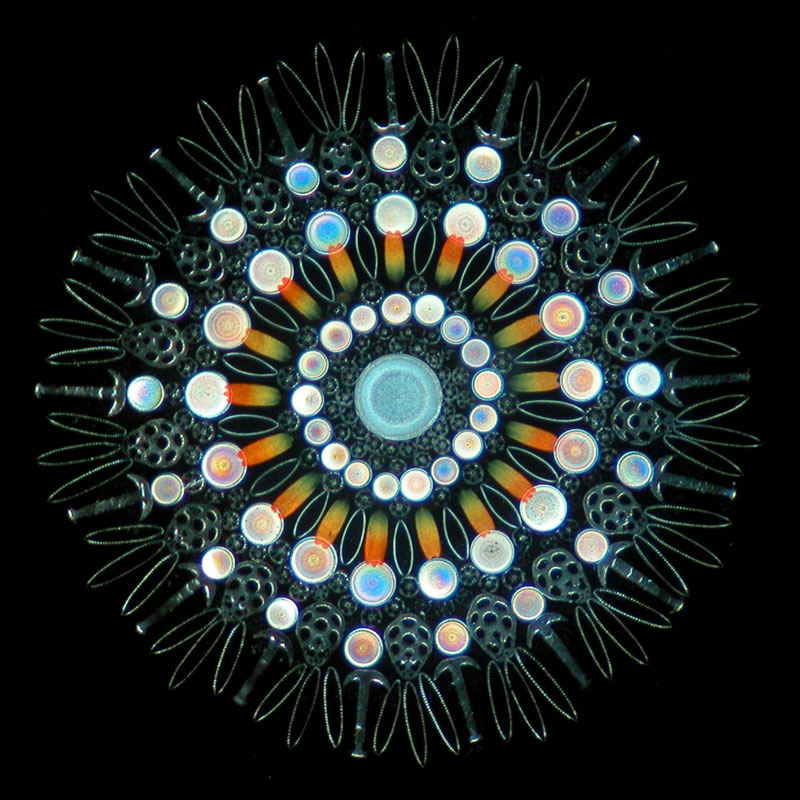

Microscopic Arrangements

Some slides allowed their makers the opportunity to show off their skills by carefully selecting tiny elements and composing them into images or geometric designs. The arrangement above contains brightly colored butterfly scales, circular diatoms and bits from a type of sea cucumber.

A Show of Skill

The circular pattern of the arrangement within this slide is visible to the naked eye. Mounters assembled these types of slide while looking through a microscope with help from tools, such as boar bristles and cat's whiskers, according to Lynk.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

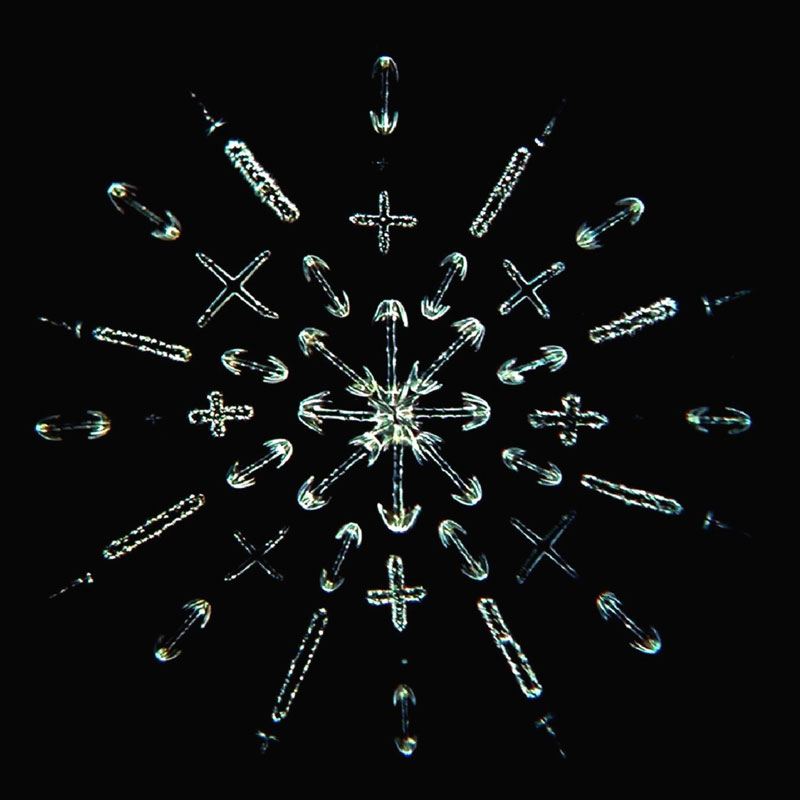

Skeletal Snowflake

This arrangement is made up of the tiny hard structures found inside sponges. Called spicules, these are a sponge's structural elements, not unlike bones in a skeleton.

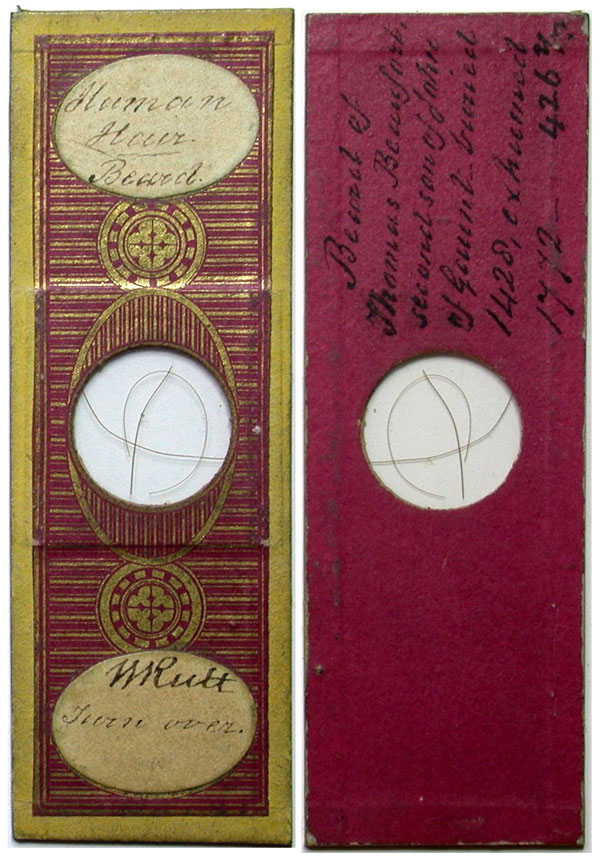

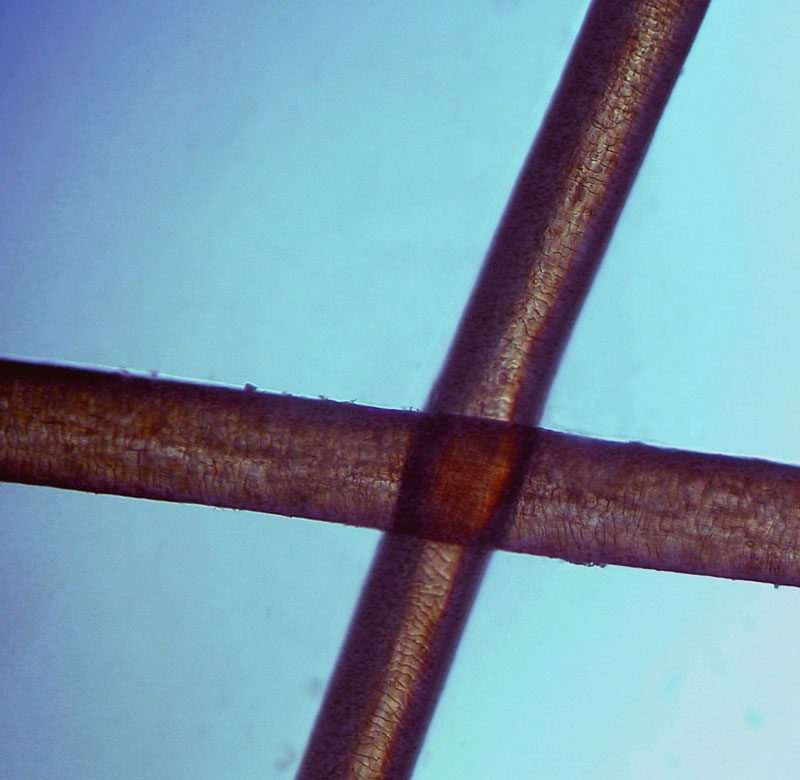

A Morbid Sight

This slide, shown both front and back, contains beard hairs taken from Thomas Beaufort, who died roughly four centuries before the slide was made. Lynk's research revealed that Beaufort was half-brother to King Henry IV and was made Duke of Exeter in 1410. He died in 1427, and was buried at a church in the town of Bury St. Edmund's in England, according to West Suffolk, a book about the history of the western division of the county, published in 1907. On Feb. 20, 1772, laborers found Beaufort's lead coffin and sold it for 15 shillings. His body, which had been embalmed and was perfectly preserved, according to the book, was mutilated — with his arms cut off at the elbows and skull sawed to pieces before he was reburied.

A Closer Look

The maker of this slide, C.M. Topping, had connections to the Royal College of Surgeons, where some of Beaufort's body parts were reportedly preserved.