What New Zealand's Deadly Quake Can Teach Cities

Newly uncovered details about the earthquake that rocked New Zealand in February may offer grim lessons regarding the potential threat of fault lines running through urban centers.

The relatively moderate earthquake that struck the city of Christchurch in February surprised many with its destructive power. The magnitude 6.2 temblor killed more than 180 people and damaged or destroyed more than 100,000 buildings, the deadliest quake to strike New Zealand in 80 years. Much of the damage came from a phenomenon called liquefaction, where soils are shaken and begin to behave as a liquid, undermining buildings and other structures.

"The high intensity of shaking was greater than expected, particularly for a moderate-size earthquake, and the liquefaction-induced damage was extensive and severe," said Erol Kalkan, a research structural engineer and manager of the National Strong Motion Network with the U.S. Geological Survey and guest editor of a special issue of the journal Seismological Research Letters focused on the Christchurch earthquake out today (Nov. 1).

The degree of damage was particularly surprising given the relative preparedness of the city.

"Compared to the earthquake that destroyed much of Haiti, the scale of disaster in Christchurch may seem small," added geoscientist Jonathan Lees at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and editor-in-chief of Seismological Research Letters. "Christchurch, however, was constructed using much better technology and engineering practices, raising a very sobering alarm to other major, high density western urban centers."

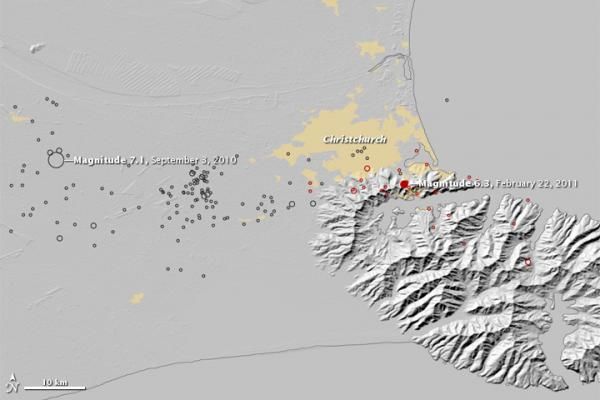

The Christchurch earthquake followed a larger magnitude 7.1 quake in Darfield, New Zealand, in September 2010 that was less destructive and did not cause any deaths. Both earthquakes ruptured along previously unmapped faults, but the corresponding damage was quite different. The differences seen between the sites helped offer scientists insights as to why the Christchurch earthquake proved so devastating.

Key quake lessons

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One key lesson regarding the unexpected intensity of the Christchurch quake may have to do with the city's foundations. Much of Christchurch was once swampland, beach dune sand, estuaries and lagoons that were drained as the area was settled. As a result, large areas beneath the city and its environs are characterized by loose sand, gravel and silt — soil types highly susceptible to liquefaction. Widespread damage induced by liquefaction within the central business district of the city required 1,000 buildings to be demolished.

Another lesson comes from the basin of bedrock that lies under Christchurch: The shape and material of this basin likely amplified ground shaking, trapping and focusing seismic energy within it just as a lens bends light.

"Many urban areas are built over soft sediments and in valleys or over basins — for example, the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles Metropolitan," Kalkan said. "These are urban areas that sit atop geological features that may exaggerate or amplify ground motion, just as Christchurch experienced."

Future changes

Profound changes in building codes are getting evaluated for the next generation of structures in New Zealand, ideas that may influence cities in the United States and the rest of the world that face similar hazards.

"One of the major lessons to learn from Christchurch is to make the foundations of these buildings much stronger to reduce damage from liquefaction," Kalkan told OurAmazingPlanet. "However, the most important lesson may be to avoid construction on soft soils where liquefaction is a problem."

"This is just the beginning for New Zealand," Kalkan added. "I'm sure we'll see many changes down the road in their construction practices."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.