Butterfly Scales & Beard Hair: Antique Slides Reveal Obsession with Science

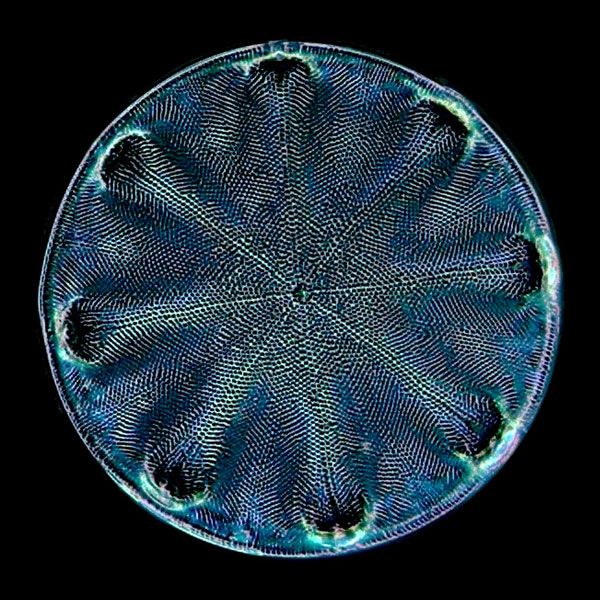

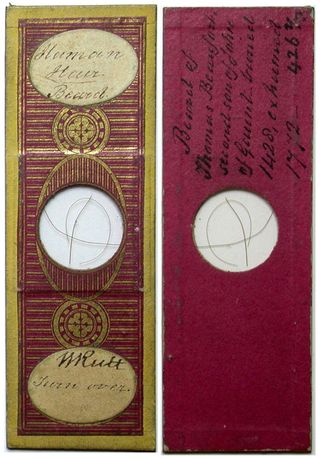

A miniature photograph of the moon, beard hairs whose owner has been dead for centuries, a shaving of Egyptian mummy bone, flowerlike patterns constructed from butterfly scales and algae called diatoms, and engravings of biblical text.

During a good part of the 19th century, called the Victorian times, a peek through a microscope could reveal very different sights than ones we'd expect to see today. In the mid- to late-1800s, microscopes were not only instruments of scientific discovery, but they were tools for popular entertainment, particularly in Britain. And an industry of inventive slide makers sprung up to feed the public appetite for this new way of seeing.

About 150 years later, it's still possible to see some of these strange and beautiful sights, and to learn about the mounters who assembled them, thanks to antique slide collectors who delve into the lives of those who made these microscopic pieces of art. [Nature Under Glass: Gallery of Victorian Microscope Slides]

One of the strangest slides in collector Howard Lynk's collection contains three innocuous-looking brown hairs, which came from the beard of a man named Thomas Beaufort, who was half brother to King Henry IV. Beaufort died in 1427, and about 350 years later, in 1772, his coffin was exhumed and sold, and his body mutilated. Somehow, perhaps via the Royal College of Surgeons, his beard hairs made their way into the hands of a prominent and prolific slide maker.

"The slides are all over the map. They were trying to make a living, so if they had something they thought would catch some interest, they put it onto a slide," said Lynk, a collector who owns and curates the website Victorian Microscope Slides.

But his collection contains much more than oddities. Slides like those containing a single, luminous diatom; the exoskeletons of insects cleaned of their innards; and a bit of tongue with the tiny blood vessels highlighted in red reflect a burgeoning interest in the natural world at the time.

Who were they?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Aided by historical documents and old books available through Google, Lynk and a collaborator, Brian Stevenson, a professor of microbiology at the University of Kentucky, College of Medicine, who uses microscopes in his professional life as well, have looked into the lives of the slide makers.

"Part of the fun of this is there are so many unknowns," Stevenson said. "That is a big part of the fascination for me."

Stevenson, who has his own microscopy website, has investigated the lives of a number of the professional slide preparers, looking at census, marriage, birth and death records, as well as databases containing historical publications.

One of his current fascinations is a slide maker by the name of William Darker. Darker was known for his mineral slides, which he ground so that light — directed by mirrors — would shine through the stone, revealing crystals or tiny shells in limestone.

Stevenson found that Darker was also a major manufacturer of scientific equipment, who worked with the likes of Michael Faraday, the physicist and chemist who discovered electromagnetic induction, and Lord Kelvin, who developed the Kelvin scale of temperature measurement and the idea of absolute zero. He also worked on waterproofing the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable.

His personal life is something of a mystery, though. He was married by 1850, but in the decades that followed his wife was never listed as residing at home, although children showed up there. When Stevenson did find evidence of her whereabouts, she was in prison. Then he found that, in 1864, Darker shot himself to death.

A quote from a contemporary, the prominent physicist John Tyndall, offers some explanation: "This man's life was a struggle, and the reason of it was not far to seek. No matter how commercially lucrative the work upon which he was engaged might be, he would instantly turn aside from it to seize and realize the ideas of a scientific man."

Popular science

"In contemporary terms, science was the 'in thing' in the second half of 19th century," said Bernard Lightman, a professor of humanities at York University in Canada and author of the book "Victorian Popularizers of Science" (University Of Chicago Press, 2010).

Rising literacy during the 19th century sparked a demand for books, which could be produced more cheaply due to advancements in publishing. Science books caught on, in particular the anonymous book "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation," which became a sensation when in 1844, it put forward that everything in existence evolved from an earlier form, setting the stage for Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of Species," published 15 years later, according to Lightman.

Science wasn't just reaching people through cheap books. Museums and international exhibitions of technological and industrial wonders also brought science, including microscopy, to the public.

Meanwhile, microscopes had become cheaper and widely available. Microscope clubs formed and periodicals promoted microscopy. People not only bought pre-made slides, but made their own collecting trips to gather things to look at, often to the beach.

A new world view

Just as literacy and the popularity of books exploded in the 19th century, a revolution in visual communication took place. Images — like book illustrations, panoramas and illusions — became more plentiful and popular. New technologies explored how we see, like the stereoscope, which recreates three-dimensional vision, and sights once available to only a few, like the view through a microscope or telescope, became widely available. Photography was invented in the first part of the century, and then applied more to scientific subjects as time progressed; and the scientific study of the eye became important, according to Lightman. [Eye Tricks: Gallery of Visual Illusions]

"People start to think more about the process of seeing, and what does that tell us about the natural world," he said.

Microscopes became a focal point in a contest to define the nature of science. For those who embraced natural theology, which finds evidence of the divine in the design of the natural world, the exquisite detail visible through the microscope was evidence of God's hand.

Others, like the biologist Thomas Huxley, saw only the material world through a microscope. Huxley believed the information it revealed should be analyzed according to the standards of professional science. He saw the microscope as an important instrument in the laboratory of the professional scientist, where he believed science should be done.

Ultimately, this may have contributed to the microscope's waning popularity later in the century. The microscope became an instrument for professional scientists, science became more specialized and less accessible to everyone, and the notion of using the microscope to uncover the awe of the natural world began to fade, Lightman said.

You can follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.