A NASA space telescope's discovery of a group of "invisible" stars and one ultra-bright stellar dynamo is shedding new light on pulsars, fast-spinning objects known as the lighthouses of the universe.

In two new studies announced Nov. 3, researchers used NASA's Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope to find nine previously unseen pulsars, and to peg one hyper-spinner as the brightest and youngest of its kind.

The new discoveries should help astronomers better understand pulsars, researchers said — but they're also likely to raise as many questions as they answer.

"These are fantastic, amazing, unexpected results," Victoria Kaspi, a physics professor at McGill University in Montreal, told reporters today (Nov. 3). "But now we have our work cut out for us, to understand what the impact is on the galactic census and our understanding of the evolution of stars." [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

Lighthouses of the universe

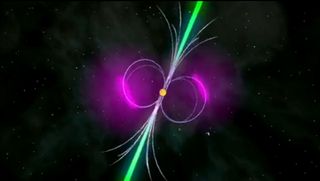

Pulsars form when massive stars die in supernova explosions and their remnants collapse into compact objects composed entirely of particles called neutrons.

These resulting neutron stars are about the size of a city. If enough mass is squeezed into this relatively tiny space, a pulsar is born: Conserved angular momentum causes the star to spin very rapidly, and to emit a ray of high-energy light that sweeps around like a lighthouse beam.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pulsars appear to pulse because astronomers can only detect their radio or gamma-ray beams when they're pointed at Earth. Most pulsars spin between 7 and 3,750 revolutions per minute, though some, known as millisecond pulsars, can rotate at up to 43,000 revolutions per minute.

The Fermi space telescope is a good tool for finding and characterizing some types of pulsars, because its instruments pick up gamma-ray light very well. And researchers put it to work in the two new studies.

"Invisible" pulsars

One team of astronomers used Fermi data to find nine previously unknown, relatively dim gamma-ray pulsars, bringing the known number of such objects to more than 100. Before Fermi's launch in 2008, just 7 gamma-ray pulsars were known, researchers said.

The scientists created a new algorithm and used a supercomputer to help trace gamma-ray photons back to their parent pulsars. That was a tall order, because the team had precise arrival times for just 8,000 photons picked up by Fermi — an average of just eight photons or so per day since the telescope's launch.

"It's like overhearing tiny fragments of a conversation at a cocktail party and trying to figure out what the discussion was about," said study co-author Bruce Allen, director of the Albert Einstein Institute in Hanover, Germany.

But the team's methods worked. The nine new pulsars they found emit less gamma radiation than previously known pulsars and spin between 180 and and 720 times per minute, researchers said.

The study will be published in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Bright, young star oddity

In the other study, which was published today in the journal Science, another team of researchers trained Fermi on a globular cluster — a huge conglomeration of stars — 27,000 light-years away, in the constellation Sagittarius.

They picked up huge amounts of gamma-ray radiation, so much so that they initially thought it had been produced by a big group of millisecond pulsars. But further digging revealed that not to be the case.

"I think this is quite amazing," said study lead author Paulo Freire, of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany. "We thought this was 100 millisecond pulsars, and now we see it's a single one."

That ultra-luminous millisecond pulsar is called J1823-3021A, whose radio emissions were first observed in the 1990s. But its newly observed gamma-ray beams make J1823-3021A the brightest millisecond pulsar known. The researchers determined its age to be 25 million years, making it the youngest as well. Most of its ilk are a billion years old or so, researchers said.

The fact that J1823-3021A was found in a globular cluster makes its youth an even bigger surprise, Kaspi said, because clusters are thought to be composed primarily of old stars.

"It's a bit like finding Justin Bieber when you thought you were at a Stones concert," she said.

J1823-3021A's extreme luminosity may have astronomers rethinking their ideas about how such objects form. And its youth suggests that hyper-energetic millisecond pulsars are likely more common throughout the universe than astronomers had imagined, researchers said.

Fermi may help researchers get to the bottom of these and other spinning-star mysteries before its work is done.

"It's very fair to say that the future for pulsar science with Fermi is very bright indeed," said Pablo Saz Parkinson of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to Live Science. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.