50-Legged Creature May Have Been Top Predator of Ancient Seafloor

An ancient cockroach-like creature nearly a foot long once skittered along the seafloor in what is now Canada, a new fossil find reveals.

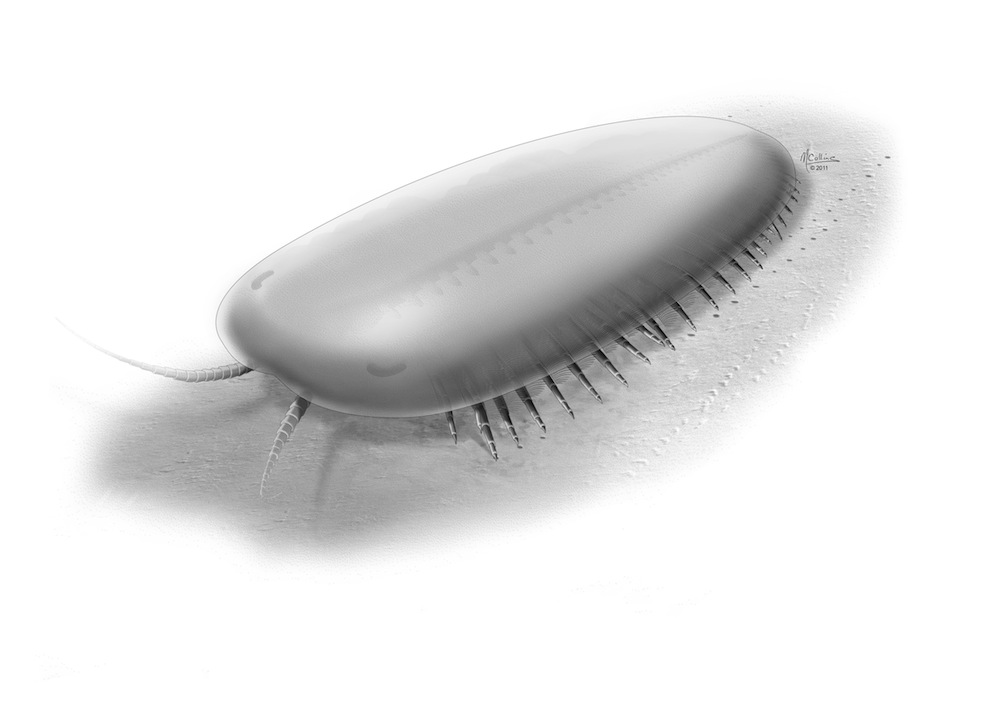

The fossil, a series of 500-million-year-old tracks, captured the movement of a large seafloor-dwelling creature with at least 25 pairs of legs. The animal was likely an arthropod called Tegopelte, a rare giant very rarely found fossilized. Arthropods are invertebrates with exoskeletons, a group that includes today's crustaceans and insects.

Reporting the discovery Tuesday (Nov. 8) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers led by Nicholas Minter of the University of Saskatchewan in Canada suggest that Tegopelte was a fearsome predator or perhaps a quick-moving scavenger, capable of "rapidly skimming across the seafloor" with only a few of its many legs touching the ground at a time.

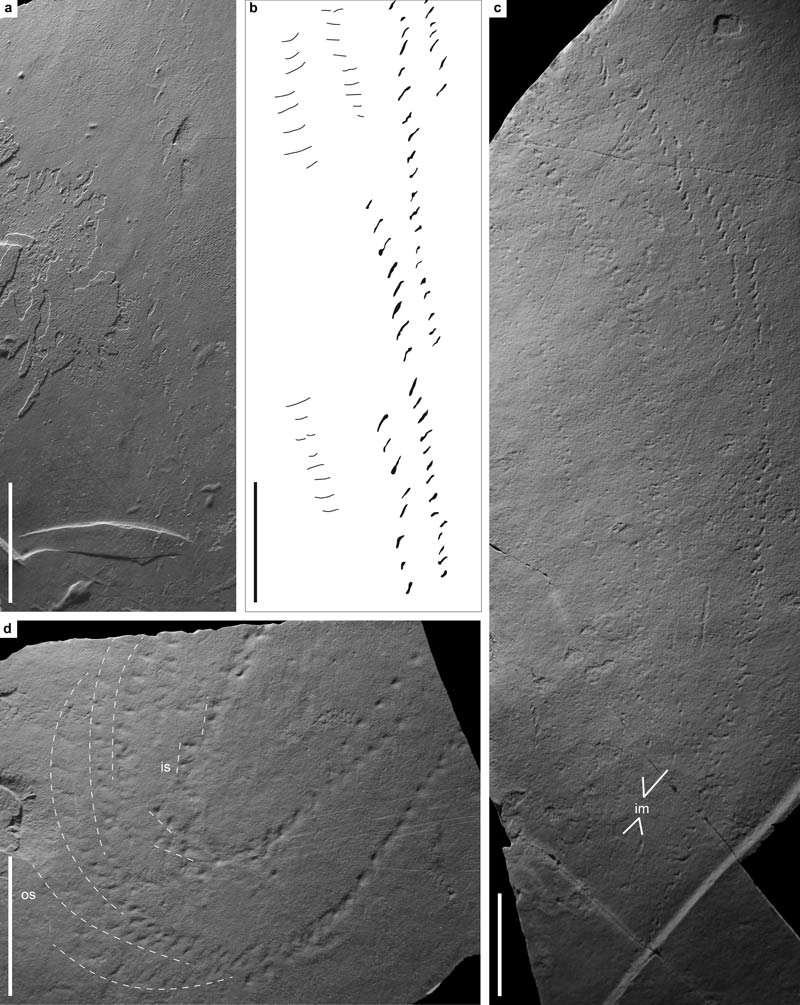

The new fossils, five trackways made by the ancient arthropod, were uncovered in two locations in Yoho National Park in British Columbia in a geologic formation called the Burgess Shale. The longest track extended more than 9 feet (3 meters), and the footprints were set more than 4 inches (100 millimeters) apart, suggesting a good-sized critter with a wide stance.

The researchers compared the tracks with the anatomy of known arthropods from the time period and concluded that the most likely footprint-maker was Tegopelte. This creature, which looked a bit like an enormous beetle and which was possibly related to trilobites, could grow to at least 11 inches (280 mm) long and 5.5 inches (140 mm) wide, with 33 sets of legs. That made it the best fit for the tracks, which represented at least 25 pairs of pattering feet.

Tegopelte's flexible, bug-like exoskeleton likely allowed it to make the sharp turns evidenced in some of the tracks, the researchers wrote. The tracks also reveal sections where the animal "skimmed" along the seafloor with only a few legs bearing weight. The tracks suggest a fast-moving creature, the researchers wrote. It could have skittered to avoid predators, but the animal was twice the size of any other Burgess Shale arthropod, the researchers wrote. That size advantage suggests that the animal could have been a top predator itself.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.