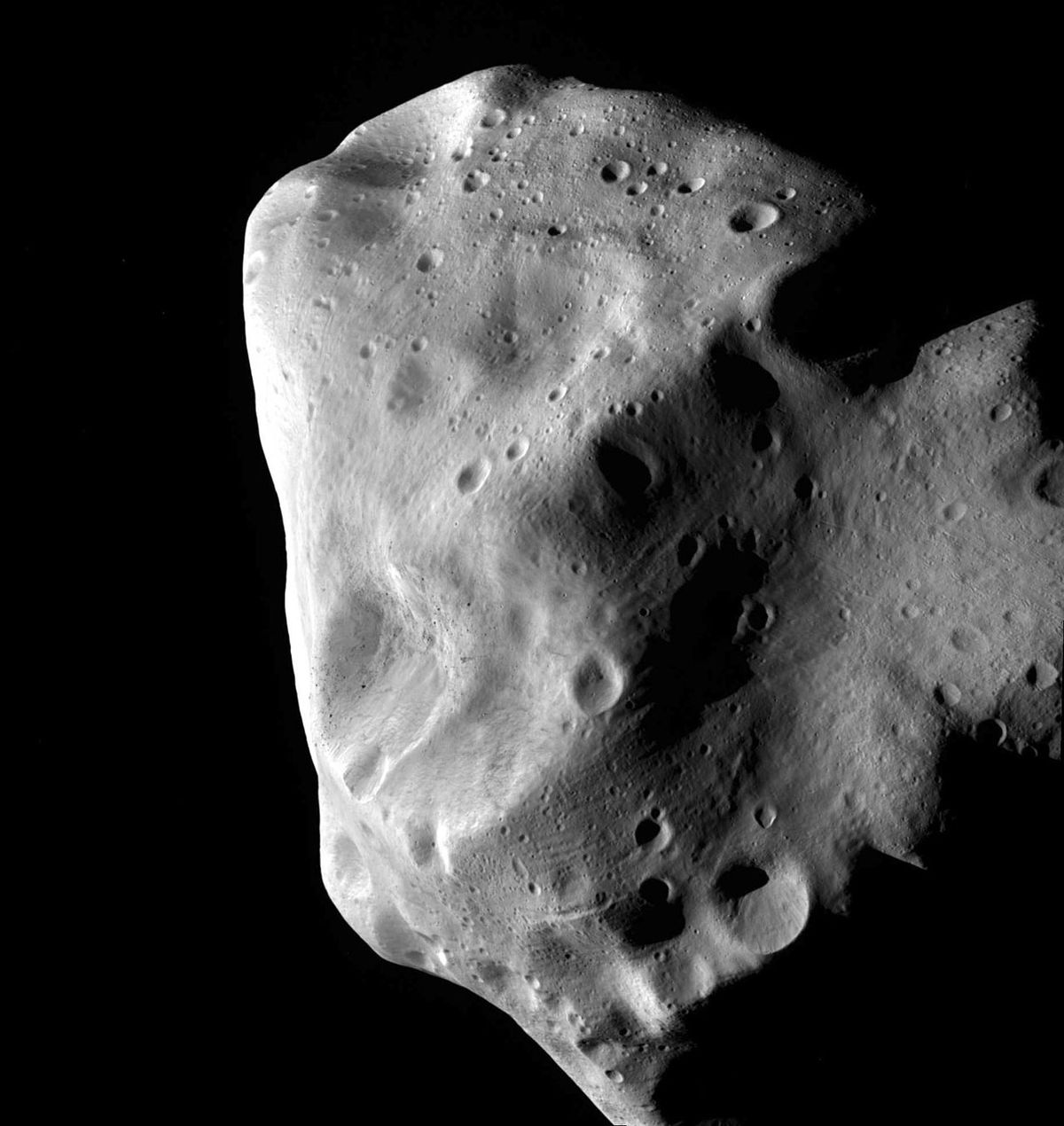

Battered Asteroid Lutetia a Rare Relic of Earth's Birth

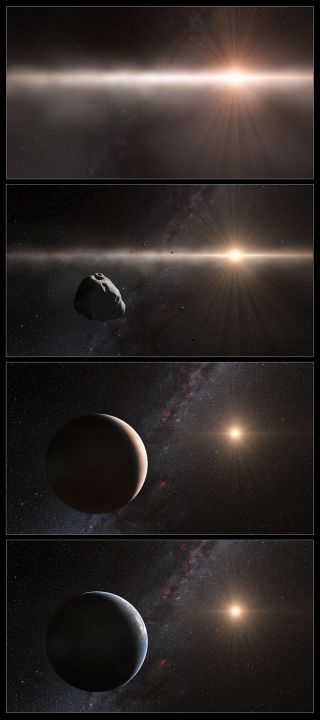

The oddball asteroid Lutetia is a rocky remnant of the material that formed Earth, Venus and Mercury about 4.5 billion years ago, a new study suggests.

Asteroid Lutetia is a battered space rock pitted with craters. Its composition suggests it likely formed close to the sun in the same cloud of material that eventually coalesced into the inner solar system's rocky planets. But then it was booted out to its current location in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, most likely after a run-in with a young planet, researchers said.

"We think that such an ejection must have happened to Lutetia," said study lead author Pierre Vernazza, of the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille in France, in a statement. "It ended up as an interloper in the main asteroid belt, and it has been preserved there for four billion years."

Studying Lutetia

Vernazza and his team used a variety of instruments to investigate Lutetia, which is about 62 miles (100 kilometers) across. [Video: Lutetia Booted to Asteroid Belt]

They studied data from the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft, which made a close flyby of asteroid Lutetia in July 2010. And they looked at observations from the European Southern Observatory's New Technology Telescope in Chile, as well as data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and its Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii.

The result is the most complete spectrum of an asteroid ever assembled, researchers said. That spectrum was then compared to that of different types of meteorites collected on Earth's surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lutetia's spectrum matched that of one particular class of meteorite called enstatite chondrites, which are known to date from the early solar system. Enstatite chondrites are thought to have formed close to the sun and to have served as building blocks for the rocky planets, especially Earth, Venus and Mercury, researchers said.

The implication is that Lutetia also originated close to the sun, not out in the main asteroid belt where it currently sits.

The study will be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Icarus.

Booted to the belt

Lutetia was likely flung out to its present position by a gravitational interaction with one of the solar system's rocky planets, researchers said. It may also have had an encounter with Jupiter while migrating to its current orbit.

Lutetia's birthplace makes the space rock pretty special. Astronomers have estimated that just 2 percent of the bodies that formed where it likely did ended up in the main asteroid belt. Most space rocks in that region were gobbled up by the newly forming rocky planets.

So astronomers could potentially learn a lot about our solar system's history by studying Lutetia further, researchers said.

"Lutetia seems to be the largest, and one of the very few, remnants of such material in the main asteroid belt. For this reason, asteroids like Lutetia represent ideal targets for future sample-return missions," Vernazza said. "We could then study in detail the origin of the rocky planets, including our Earth."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.