Jupiter Moon's Buried Lakes Evoke Antarctica

Some of the most frigid areas on Earth are providing scientists with tantalizing hints of water only a few miles under the icy crust of Jupiter's moon, Europa.

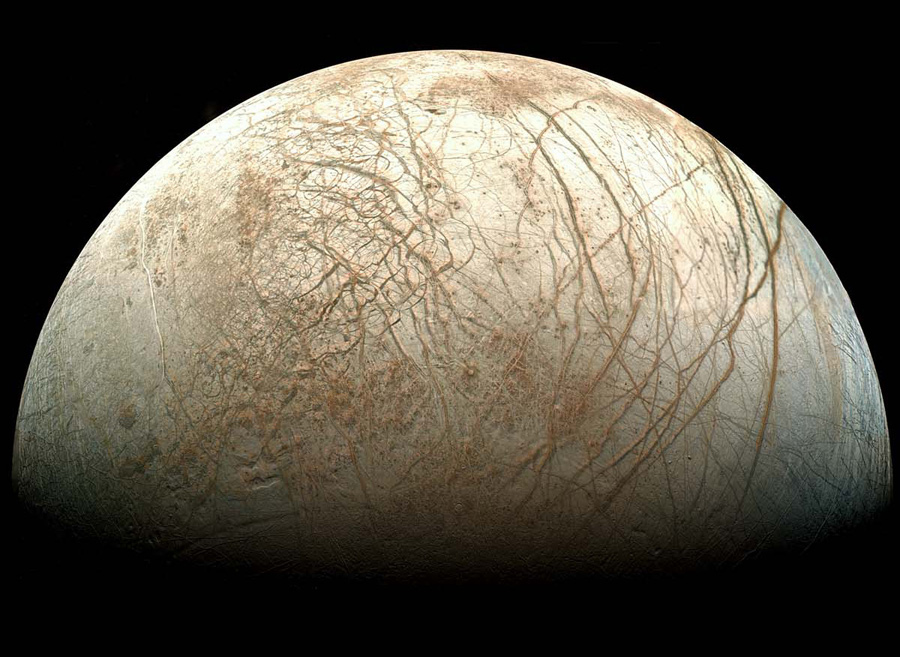

Patches of broken ice unique to the moon have puzzled scientists for over a decade. Some have argued they are signs of a subterranean ocean breaking through, while others believe that the crust is too thick for the water to pierce.

But new studies of ice formations in Antarctica and Iceland have provided clues to the creation of these puzzling features, which imply water nearer to the moon's surface than previously thought.

Hundreds of odd formations, known as "chaos terrains," are spread across Europa's icy surface. These irregular areas contain domes and iceberglike blocks that no theoretical models have been able to replicate. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

"It looks like crushed ice," Paul Schenk, of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, described one such feature to SPACE.com.

Schenk was part of a team of scientists, led by Britney Schmidt of the University of Texas at Austin, comparing Antarctic ice shelves and subglacial volcanoes to these striking features, which were imaged by NASA's Galileo satellite.

Their research was published in the Nov. 17 issue of the journal Nature.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From the Earth to (Jupiter's) moon

In Iceland, volcanoes lay beneath the ice. Their heat melts the base of glaciers and ice sheets, causing the surface to buckle in on itself and allowing stress fractures to form.

In Antarctica, saltwater fills cracks and weakens the freshwater ice. The resulting collapse leaves large freshwater ice chunks surrounded by briny ice.

Though there's no evidence for volcanoes on Europa, and the makeup of the ice is likely different from Earth's, a combination of these elements could very well be at work on Jupiter's moon, experts say.

"We were able to formulate a model for chaos formation that stacks up to observational tests," Schmidt said via email.

Rising plumes of heat

"Think of Europa as one giant ice shelf floating on a global ocean, with a really rocky core," Schenk said.

Europa's surface is cold, around minus 170 degree Celsius (minus 100 K). The bottom of the ice is slightly warmer.

"You and I might not notice the difference, but geologically it's very different," Schenk said.

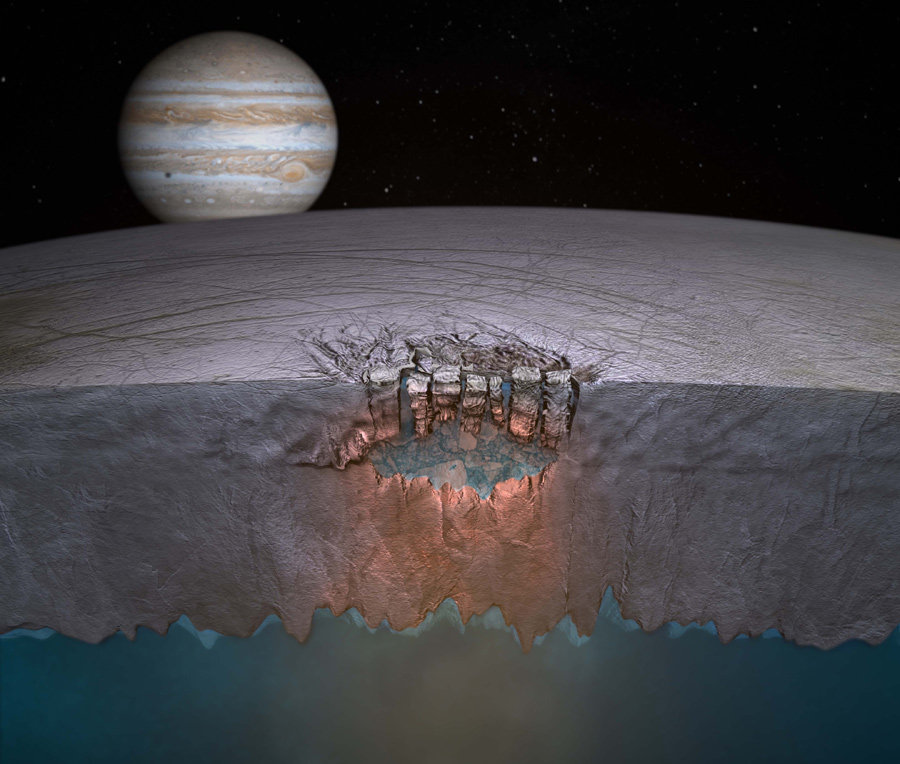

Born primarily from the tidal interactions between Jupiter and the moon, the slightly warmer temperatures are the seeds that create the odd structures. Bubbles of heat rise up through the ice toward the surface, but don't make it all the way to the frigid top.

Instead, this heat melts some of the ice into enormous lakes beneath the crust.

"On Earth, it is the volcano [melting the ice]," Schmidt said. "On Europa, it is the warm ice plume coming up from below."

Lakes beneath the ice

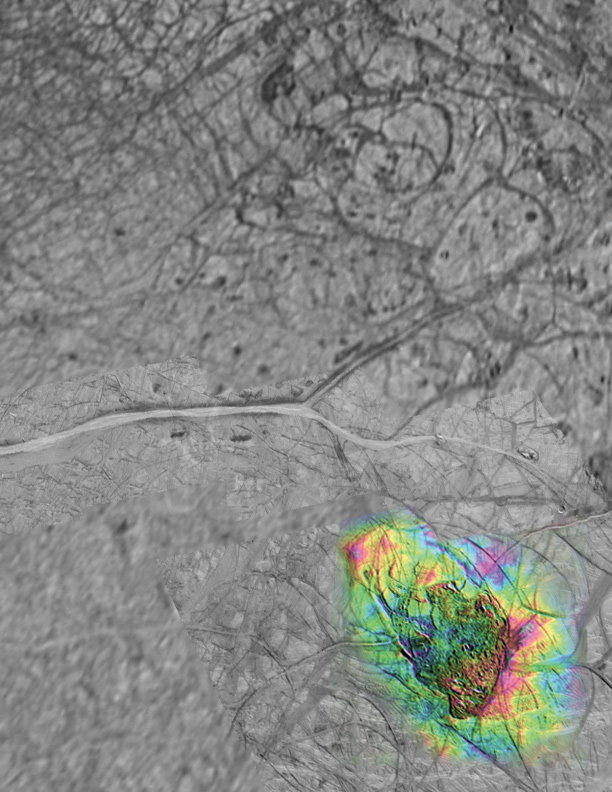

One such lake lies underneath Thera Macula, one of Europa's chaos terrains. Schmidt's team estimated that it contained as much water as all of the North America's Great Lakes combined, about 1.5 miles (3 kilometers) beneath the surface.

The ice above these lakes weakens, leaving the top layer unstable. As the crust buckles and sinks, it cracks, forming large, glacierlike blocks of ice. Salt from the surface mixes into the water and flows around the small icebergs, where it refreezes, forming peculiar domes across the surface of the moon.

Eventually, the subsurface lakes cool off and refreeze, but not for hundreds of thousands or even millions of years. Features are constantly changing. The research team even theorized that Thera Macula could have changed noticeably in the decade since NASA's Galileo captured images of the moon.

Schmidt compares this to collapsing ice shelves on Earth.

And these features are not the only potential source of water on the moon. Given the hundreds of features crisscrossing the surface of Europa, several liquid lakes are likely to exist near the surface today, only a few miles beneath the icy crust, scientists say.

"The material cycled into the ocean via these lakes may make Europa's ocean even more habitable than previously imagined," Schmidt said. "The lakes may even be habitats themselves."

This story was provided by SPACE.com , a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.