Airport Body Scanners Mostly Safe for Travelers, Experts Say

Travelers in U.S. airports who are screened by body scanners are unlikely to encounter enough radiation to promote cancer or damage their cells, experts told MyHealthNewsDaily today.

Body scanners that use X-rays will not be allowed in airports in Europe due to concerns over the devices' potential health risks, according to a ruling issued this week.

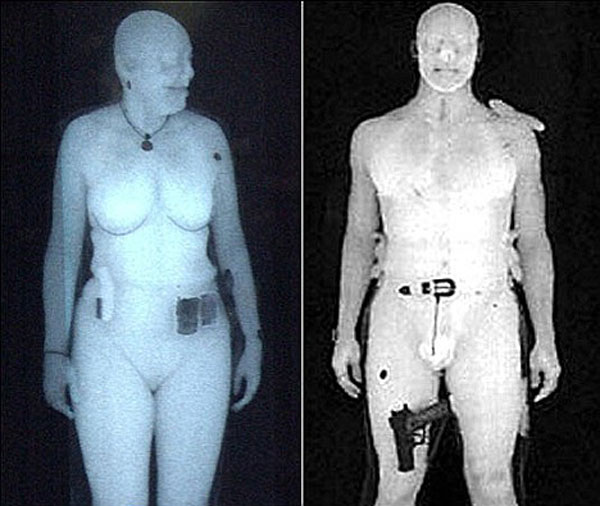

There are about 250 of these scanners, referred to as "backscatter scanners" because they emit X-rays which bounce off the body to create an image, in use in the U.S.

The news from Europe comes just a few weeks after the news organization ProPublica released an investigational report that argued the health risks from these devices may have been understated. According to David Brenner, director of the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, radiation from airport scanners may be causing an extra 100 cases of cancer in Americans each year, the ProPublica article says.

However, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) says these scanners use a low dose of radiation, about 0.15 microsieverts. This dose is equivalent to the radiation a person would be exposed to in two minutes of flying in an airplane, the TSA says. A person would have to be screened more than 1,000 times per year in order to exceed the yearly radiation dose limit.

So how safe are airport scanners?

The seemingly opposing messages from the TSA and ProPublica may be due to the very small doses of radiation in question.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the effects of high radiation doses are well-known, "there's a huge area of uncertainly around the low dose," said Dr. Jacqueline Williams, a radiation expert at the University of Rochester in New York.

Radiation can damage a cell's DNA, which may turn the cell cancerous. But whether this always happens at low doses, and what the subsequent risk of cancer might be, is unclear, Williams said.

As far as researchers can tell, the risks from low doses of radiation appear to be negligible, Williams said. Williams pointed to the case of the nuclear accident at Chernobyl, which released a plume of radioactive material into the environment — only an increased risk of thyroid cancer has been found among people living near the site. The risk of other cancers does not appear to be elevated, Williams said.

In fact, some radiation exposure may be beneficial, said Dr. Mansoor Ahmed, radiation biologist at the University of Miami School of Medicine, because it activates mechanisms inside the cell to repair cellular DNA.

"I think it is pretty safe," Ahmed said of the scanners.

But some may be more vulnerable

That being said, there are some people who may be particularly vulnerable to radiation from scanners, Ahmed said. These would be individuals with hereditary conditions that impair their cells' ability to repair DNA, Ahmed said. People with these conditions should take extra precautions when flying, he said.

Ahmed also said careful measures should be taken to ensure the scanners do not emit more radiation than the TSA claims.

"I think the authorities have to fully concentrate on the safe delivery of that precise radiation [dose]," Ahmed said. The scanners should not be able to emit radiation beyond a certain limit, he said.

Brenner has previously argued that the doses of radiation to the scalp and skin from airport scanners may be 20 times higher than the doses claimed by the TSA. "It's still a low dose, but it’s much more than what’s usually said," Brenner said.

Pass it on: The risks of low doses of radiation, such as those used by airport body scanners, are uncertain, but so far appear to be negligible.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner. Find us on Facebook.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.