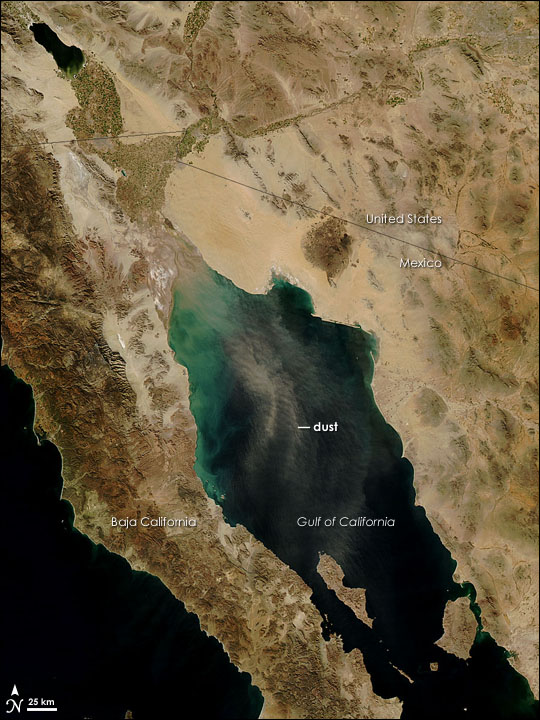

How Did the Gulf of California Form So Quickly?

A new look at geologic evidence shows that the Gulf of California, the sea that separates the Baja California peninsula from mainland Mexico, formed in as little as 6 million to 10 million years — much faster than most other ocean basins across the globe.

Six to 10 million years may sound like an eternity, but geologically speaking, it's the blink of an eye. Large basins, such as the Atlantic Ocean, can rift for 30 million to 80 million years before the crust completely ruptures, spilling magma and beginning the process of sea-floor spreading.

But the Gulf of California completed this act in near-record time, thanks to that old real estate motto: location, location, location.

Northern Arizona University geologist Paul Umhoefer said that the sea's rapid formation is likely due to its location along a tectonically active continental margin (the area where thin ocean crust meets thick continental crust) with three key characteristics: a hot, weakened crust, rapid plate motion, and strike-slip faulting (the side-by-side rubbing of plates along a fault).

Three keys

Umhoefer's study, detailed in the November issue of the journal GSA Today, arrived at those three factors based on findings by geologists and marine geophysicists working in the region over the past decade.

First, the continental margin inherited a swath of hot, weak crust from a volcanic chain that was active in the area around 12 million years ago, immediately before Baja California began to pull away from mainland Mexico.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We know that a great deal of heat, or something like a volcanic chain, almost always contributes to a weaker crust," Umhoefer told OurAmazingPlanet. Weaker crust is, of course, easier to break.

This region of hot, weak crust straddled two relatively fast moving plates: the Pacific plate and the North American plate, which pull diagonally away from each other at a rate of about 50 millimeters per year. That's on the higher end of average plate speeds, Umhoefer said. (Tectonic plates typically move at a rate similar to fingernail growth — anywhere from about 10 to 100 millimeters per year.)

"The faster the two plates move away from each other, the higher the overall rate of faulting, and the more likely the faults will be focused into a single boundary that eventually thins and ruptures the crust," Umhoefer said.

Finally, strike-slip faulting (as happens perhaps most famously along the San Andreas Fault) is common in the region and likely to have played a major role in rupturing the Gulf of California.

"Strike-slip faults by nature are steep" — commonly near-vertical — "so they have a tendency to cut efficiently through the crust and into the mantle," which focuses the breaking along very narrow zones, Umhoefer explained.

Altogether, his study concluded, these assets combined to rift and rupture the Gulf of California at a rapid pace.

Rifting worldwide

Globally, these factors also account for stark differences between rifts at active continental margins and those in the middle of a continent, Umhoefer said.

Areas that are tectonically active before rifting begins — which usually lie at continental margins — rupture rapidly and form smaller seas, such as the Gulf of California, because they rift off small pieces of continent. Rifts that begin in the middle of a continent slowly rupture and form larger basins, as in the case of the formation of the Atlantic Ocean, because they tend to break off large chunks of continental crust.

"How do continents that have active tectonics, like western North America, respond to rifting versus a place that's been relatively quiet? That's a question the research community is trying to answer," Umhoefer said.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.