Runaway Stars May Be Rejects from Stellar Threesomes

Most "runaway stars" that are zipping through space may be fleeing the breakup of cosmic threesomes, scientists say.

Most of the stars in our galaxy move relatively slowly. However, approximately 20 percent of all massive stars in the Milky Way travel unusually quickly, at more than 67,000 mph (108,000 kph).

The origin of these runaway stars has puzzled astronomers for nearly 50 years. Some suspect they were once partners of stars that exploded as supernovas. Others speculate they were slung through space by the pull of other stars' gravity.

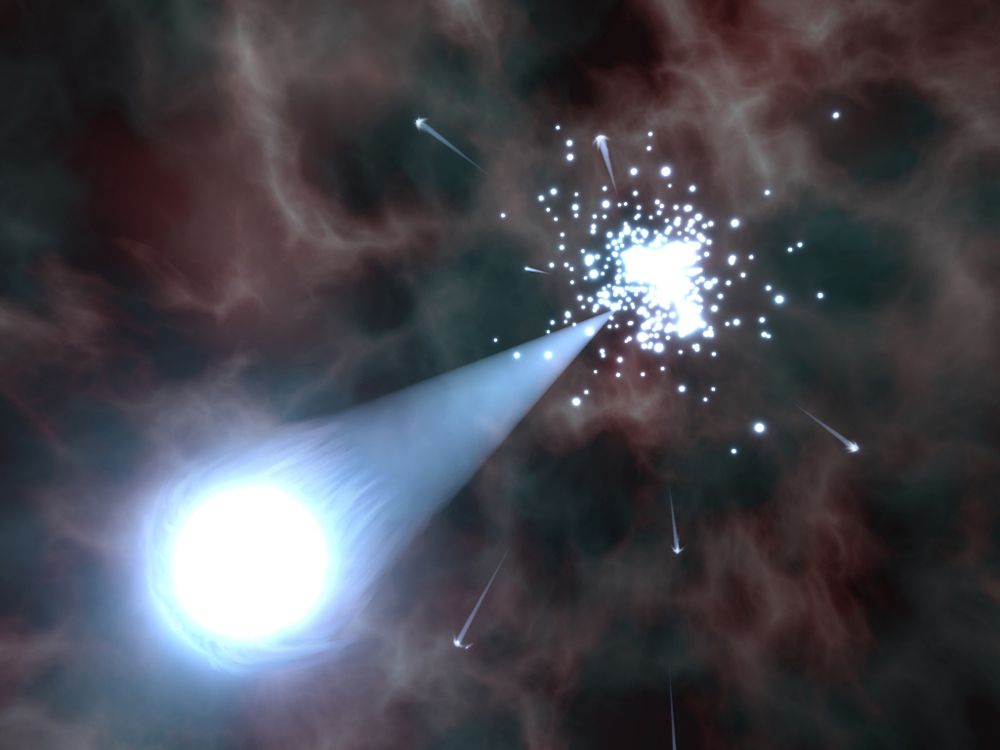

But now, researchers find that most runaway stars may arise from ménages à trois – encounters with binary systems, or paired stars, within the centers of clusters of stars. The runaways get slung outward after strong gravitational interactions with the binaries.

To reach this finding, scientists developed state-of-the-art computer simulations of star cluster behavior. They found that models involving star clusters 5,000 to 10,000 times the mass of the sun compared well with actual observations of the more than 100 runaway stars detected around young clusters in our galaxy, those younger than 1 million years old.

One consequence of these findings is that star clusters may "be born with densities far higher than observed in today's clusters," said study co-author Simon Portegies Zwart, a computational astrophysicist at the University in Leiden in the Netherlands.

Once-dense star clusters may have shrunk over time after hurling stars away from them.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"One can learn possibly more about the history of a star cluster by looking away from it," Portegies Zwart told SPACE.com.

To seek further proof of this model, Portegies Zwart and his colleagues could try tracing the trajectory of runaway stars backward to see if they do in fact emerge from binary systems, he said.

Portegies Zwart and colleague Michiko Fujii detail their findings online in the Nov. 17 issue of the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.