Ancient Human's Head Trauma Points to Foul Play

An ancient argument may have resulted in someone cracking the head of an ancient early human called the Maba Man. A healed lesion on this 200,000-year-old skull may have come from violent trauma, though not bad enough to have killed him.

"People are social mammals, we do these kinds of things to each other," study researcher Erik Trinkaus, of Washington University in St. Louis, told LiveScience, referring to interpersonal aggression. "It's another case of long-term survival of a pretty serious injury."

The Maba Man skull pieces were found in June 1958 in a cave in Lion Rock, near the town of Maba, in Guangdong province, China. They consist of some face bones and parts of the brain case. From those fragments, researchers were able to determine that this was a pre-modern human, perhaps an archaic human. He (or she, since researchers can't tell the sex from the skull bones) would have lived about 200,000 years ago, according to Trinkaus.

Skull depression

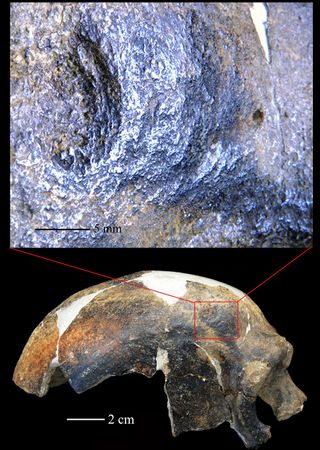

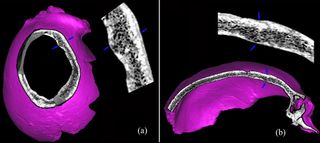

Decades after the skull bones were discovered, researcher Xiu-Jie Wu at the Chinese Academy of Sciences took a close look at the strange formations on the left side of the forehead, using computed tomography (CT) scans and high-resolution photography. The skull has a small depression, about half an inch long and circular in nature. On the other side of the bone from this indentation, the skull bulges inward into the brain cavity.

After deciding against any other possible cause of the bump, including genetic abnormalities, diseases and infections, they were left with the idea that Maba somehow hit his head. The certainties stop there, though. The researchers suggest that all they really know is the ancient human suffered a blow to the head.

"What becomes much more speculative is what ultimately caused it," Trinkaus said. "Did they get in an argument with someone else, and they picked something up and hit them over the head?"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on the size of the indentation and the force needed to cause such a wound, it's possible it was another hominid, Trinkaus said.

"This wound is very similar to what is observed today when someone is struck forcibly with a heavy blunt object," said study researcher Lynne Schepartz, from the school of anatomical sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, adding that it "could possibly be the oldest example of interhuman aggression and human-induced trauma documented."

Another possibility: Maba might have had a run-in with an animal. A deer antler would be about the right size to make the forehead mark, though the researchers don't know if it would be forceful enough to crack Maba's skull.

Healing after injury

After the whack on the head, Maba shows considerable healing, suggesting he survived the hit. It could have been months or even years later that he would have died, of some other cause. These hominids lived in groups and Maba would have been taken care of by his group mates.

Though nonlethal, the injury likely would have given Maba some memory loss, the researchers said. "This individual, which was an older adult, received a very localized, hard whack on the head," Trinkaus said. "It could have caused short-term amnesia, and certainly a serious headache."

"Our conclusion is that most likely, and this is a probabilistic statement, [the injury] was caused by another person," Trinkaus said. "Ultimately all social animals have arguments and occasionally whack another and cause injury."

The study was published today (Nov. 21) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Most Popular